The History of Nubia. The Neolithic Period

By the time of the Neolithic Period (ca. 50003000 BC), there was a distinct transition into settled life, with an increased reliance on domesticated livestock and eventually the cultivation of domesticated crops in certain areas. It has been suggested that a shift in the river’s location, as well as increasing aridity near the beginning of the period, led to the movement of the population into the wadis of the eastern Sahara.

The regions to which migrants moved were more ecologically favorable for growing crops and herding animals, resulting in significant changes to patterns of living and food production. Seasonal sites located along the Nile were occupied only in the dry season, in order to be adjacent to a source of water; other sites were near the edge of the seasonally inundated floodplain.

Most Neolithic sites show evidence of domesticated animals, personal adornments made out of bone and ivory, a lithic tradition (bone and stone), grinding stones, and ceramic manufacture, as well as burials and mortuary practices. The huts making up these communities were most likely constructed of reed or reed mats. Some settlements included hearths set into areas of paved sandstone, as found at al-Shaheinab, near Khartoum in Upper Nubia.

Another site, near Kerma, dating to 4500 BC, much later in the Neolithic, has rectangular structures, possibly for fences and palisades, as well as circular structures with post holes and hearths. Most archaeologists agree that the Neolithic in Nubia is characterized by large base camps and seasonal smaller camps used for herding animals, in addition to areas in Lower Nubia and northern Upper Nubia that were more permanently settled by farmers.

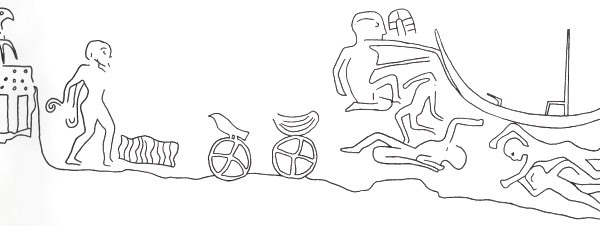

Figure. Rock inscription at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman

A majority of Neolithic settlements include burial sites. Early in the Neolithic, burial plots were grouped together into small cemeteries; by the later Neolithic there existed large, complex cemeteries. The deceased were buried mostly in circular pits, in a contracted position surrounded by numerous grave goods. The complexity and variation of goods indicated their social rank, wealth, and possibly their occupation during life, as well as the rituals associated with mortuary practices.

The site of Kadero, north of Khartoum, consists of two settlements and a cemetery. The settlement has yielded Neolithic grinding stones, domestic animals, pottery, and lithics. The cemetery contains at least two hundred burials of male and female adults and children interred over a long period of time.

The burials reveal social differentiation, ranging in complexity from graves including little or no funerary goods or pottery to wealthier graves containing varied and elaborate funerary items such as hippopotamus ivory, stone palettes, and adornments like carnelian-bead necklaces. Differences also appear between female and male burials, with some male burials including stone mace heads. Jacques Reinold, who examined the burial goods of one affluent female at Kadero, concluded that women may have had considerable power during this time.

Current research at Kadruka, south of the Third Cataract, yielded even more unusual finds. Some of the largest cemeteries had more than one thousand burials. As at Kadero, these cemeteries spanned a considerable period of time and showed significant social differentiation, but at Kadruka, many cemeteries also suggested complex burial practices. Stelae for the deceased were mounted near some of the graves. Elaborate grave goods consisted of leather, human figurines, bracelets, beads, and pendants; some burials even have hippopotamus-tusk containers and ostrich eggs.

These burial goods, as well as the distance of burials from the center of the cemetery, suggested to Reinold a “class-conscious society.” Many of the burials had human sacrifices placed next to the deceased, indicating some form of ritual, as well as hearths near the graves for some unknown purpose. Human sacrifices were also apparent at al-Ghaba and al-Kadada, as were animal sacrifices. At Kadruka, dog burials lie at the four cardinal points on the edge of the cemetery, signifying perhaps a protective ritual. Reinold proposes that the animal and human sacrifices may mean that intricate funerary rituals had become an integral social practice.

The site of Kadero yields evidence of domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as the cultivation of barley. The population farther north, near the Wadi Howar, also apparently relied strongly on cattle herding, perhaps because Wadi Howar had little permanent water. In Lower Nubia, by contrast, there is less evidence of cattle and goats. All Lower Nubian sites, however, have yielded bones, lithics, potsherds, and grinding stones, while others also have spears, harpoons, and cosmetic boxes, suggesting that domestication of animals may have been less prevalent than fishing, hunting, and growing crops in this area.

Neolithic pottery varies according to region, and is a useful indicator for the identification of regional groups. In the north, the pottery of the Second Cataract area is comparable to that of Upper Egypt, suggesting that the eastern Sahara as well as Egypt may have influenced development in these regions. Until after the Badarian Period (ca. 4400-4000 BC) of Predynastic Egypt, there was an essential continuity throughout the upper Egyptian and lower Nubian Nile region, which did not disappear until the third millennium, that is, around the time of state formation in Egypt.

Date added: 2023-10-02; views: 775;