Antecedent-Consequence Research. Personality

Personality. Research conducted since the 1970s has sought to identify what type of person is likely to use computers and related information technologies, succeed in learning about these technologies and pursue careers that deal with the development and testing of computer products. Most recently a great deal of attention has been given to human behavior on the Internet. Personality factors have been shown to be relevant in defining Internet behavior.

Studies indicate that extroversion-introversion, shyness, anxiety, and neuroticism are related to computer use. Extroverts are outer directed, sociable, enjoy stimulation, and are generally regarded to be ‘‘people oriented’’ in contrast to introverts who are inner directed, reflective, quiet, and socially reserved. The degree of extroversion-introversion is related to many aspects of everyday life, including vocational choice, performance in work groups, and interpersonal functioning.

Early studies suggested that heavy computer users tended to be introverts, and programming ability, in particular, was found to be associated with introversion. Recent studies reveal less relationship between introversion-extroversion and degree of computer use or related factors such as computer anxiety, positive attitudes toward computers, and programming aptitude or achievement. However, the decision to pursue a career in computer-related fields still shows some association with introversion.

Neuroticism is a tendency to worry, to be anxious and moody, and to evidence negative emotions and outlooks. Studies of undergraduate students and of individuals using computers in work settings have found that neuroticism is associated with anxiety about computers and negative attitudes toward computers.

Neurotic individuals tend to be low users of computers, with the exception of the Internet, where there is a positive correlation between neuroticism and some online behavior. Neurotic people are more likely than others to engage in chat and discussion groups and to seek addresses of other people online. It is possible that this use of the Internet is mediated by loneliness, so that as neurotic people alienate others through their negative behaviors, they begin to feel lonely and then seek relationships online.

Anxious people are less likely, however, to use the Internet for information searches and may find the many hyperlinks and obscure organization disturbing. Shyness, a specific type of anxiety related to social situations, makes it difficult for individuals to interact with others and to create social ties. Shy people are more likely to engage in social discourse online than they are offline and can form online relationships more easily.

There is a danger that as they engage in social discourse online, shy people may become even less likely to interact with people offline. There has been some indication, however, that shy people who engage in online relationships may become less shy in their offline relationships.

As people spend time on the Internet instead of in the real world, behavioral scientists are concerned that they will become more isolated and will lose crucial social support. Several studies support this view, finding that Internet use is associated with reduced social networks, loneliness, and difficulties in the family and at work.

Caplan and others suggest that these consequences may result from existing psychosocial conditions such as depression, low self-efficacy, and negative self-appraisals, which make some people susceptible to feelings of loneliness, guilt, and other negative outcomes, so that significant time spent online becomes problematic for them but not for others.

There is some evidence of positive effects of Internet use: Involvement in chat sessions can decrease loneliness and depression in individuals while increasing their self-esteem, sense of belonging, and perceived availability of people whom they could confide in or could provide material aid.

However, Caplan cautions that the unnatural quality of online communication, with its increased anonymity and poor social cues, makes it a poor substitute for face-to-face relationships, and that this new context for communication is one that behavioral scientists are just beginning to understand.

As computer technologies become more integral to many aspects of life, it is increasingly important to be able to use them effectively. This is difficult for individuals who have anxiety about technology that makes them excessively cautious near computers.

Exposure to computers and training in computer use can decrease this anxiety, particularly if the training takes place in a relaxed setting in small groups with a user-friendly interface, provides both demonstrations and written instructions, and includes important learning strategies that help to integrate new understanding with what is already known.

However, some individuals evidence such a high degree of anxiety about computer use that they have been termed ‘‘computerphobics.’’ Here the fear of computers is intense and irrational, and exposure to computers may cause distinct signs of agitation including trembling, facial expressions of distress, and physical or communicative withdrawal. In extreme cases, a generalized anxiety reaction to all forms of technology termed ‘‘technophobia’’ has been observed.

Personality styles differ when individuals with such phobias are compared with those who are simply uncomfortable with computer use. Individuals with great anxiety about computers have personality characteristics of low problem-solving persistence and unwillingness to seek help from others.

The training methods mentioned above are less likely to benefit individuals who evidence severe computerphobia or very high levels of neuroticism. Intensive intervention efforts are probably necessary because the anxiety about computers is related to a personality pattern marked by anxiety in general rather than an isolated fear of computers exacerbated by lack of experience with technology.

Gender. Studies over many years have found that gender is an important factor in human-computer interaction. Gender differences occur in virtually every area of computing including occupational tasks, games, online interaction, and programming, with computer use and expertise generally higher in males than in females, although recent studies indicate that the gender gap in use has closed and in expertise is narrowing.

This change is especially noticeable in the schools and should become more apparent in the workforce over time. In the case of the Internet, males and females have a similar overall level of use, but they differ in their patterns of use. Males are found to more often engage in information gathering and entertainment tasks, and women spend more time in communication functions, seeking social interaction online.

Females use e-mail more than males and enjoy it more, and they find the Internet more useful overall for social interaction. These differences emerge early. Girls and boys conceptualize computers differently, with boys more likely to view computers as toys, meant for recreation and fun, and to be interested in them as machines, whereas girls view computers as tools to accomplish something they want to do, especially in regard to social interaction.

This may be due, in part, to differences in gender role identity, an aspect of personality that is related to, but not completely determined by, biological sex. Gender role identity is one’s sense of self as masculine and/or feminine. Both men and women have traits that are stereotypically viewed as masculine (assertiveness, for example) and traits that are stereotypically viewed as feminine (nurturance, for example) and often see themselves as possessing both masculine and feminine traits.

Computer use differs between people with a high masculine gender role identity and those with a high feminine gender role identity. Some narrowing of the gender gap in computer use may be due to changing views of gender roles.

Age. Mead et al. reviewed several consequences of computer use for older adults, including increased social interaction and mental stimulation, increased self-esteem, and improvements in life satisfaction. They noted, however, that older adults are less likely to use computers than younger adults and are less likely to own computers; have greater difficulty learning how to use technology; and face particular challenges adapting to the computer-based technologies they encounter in situations that at one time involved personal interactions, such as automated check-out lines and ATM machines.

They also make more mistakes and take more time to complete computer-based tasks. In view of these factors, Mead et al. suggested psychologists apply insights gained from studying the effects of age on cognition toward the development of appropriate training and computer interfaces for older adults. Such interfaces could provide more clear indications to the user of previously followed hyperlinks, for example, to compensate for failures in episodic memory, and employ cursors with larger activation areas to compensate for reduced motor control.

Aptitudes. Intelligence or aptitude factors are also predictors of computer use. In fact, spatial ability, mathematical problemsolving skills, and understanding of logic may be better than personality factors as predictors. A study of learning styles, visualization ability, and user preferences found that high visualizers performed better than low visualizers and thought computer systems were easier to use than did low visualizers.

High visualization ability is often related to spatial and mathematical ability, which in turn has been related to computer use, positive attitudes about computers, and educational achievement in computer courses. Others have found that, like cognitive abilities, the amount of prior experience using computers for activities such as game playing or writing is a better predictor of attitudes about computers than personality characteristics. This may be because people who have more positive attitudes toward computers are therefore more likely to use them.

However, training studies with people who have negative views of computers reveal that certain types of exposure to computers improve attitudes and lead to increased computer use. Several researchers have suggested that attitudes may play an intermediary role in computer use, facilitating experiences with computers, which in turn enhance knowledge and skills and the likelihood of increased use.

Some have suggested that attitudes are especially important in relation to user applications that require little or no special computing skills, whereas cognitive abilities and practical skills may play a more important role in determining computer activities such as programming and design.

Attitudes. Attitudes about self-use of computers and attitudes about the impact of computers on society have been investigated. Research on attitudes about self-use and comfort level with computers presumes that cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of an attitude are each implicated in a person’s reaction to computers.

That is, the person may believe that computers will hinder or enhance performance on some task or job (a cognitive component), the person may enjoy computer use or may experience anxiety (affective components), and the individual may approach or avoid computer experiences (behavioral component). In each case, a person’s attitude about him-or herselfin interaction with computers is the focus of the analysis. Attitudes are an important mediator between personality factors and cognitive ability factors and actual computer use.

Individuals’ attitudes with respect to the impact of computers on society vary. Some people believe that computers are dehumanizing, reduce human-human interaction, and pose a threat to society. Others view computers as liberating and enhancing the development of humans within society. These attitudes about computers and society can influence the individual’s own behavior with computers, but they also have potential influence on individuals’ views of computer use by others and their attitudes toward technological change in a range of settings.

Numerous studies have shown that anxiety about using computers is negatively related to amount of experience with computers and level of confidence in human-computer interaction. As discussed, people who show anxiety as a general personality trait evidence more computer use anxiety. In addition, anxiety about mathematics and a belief that computers have a negative influence on society are related to computer anxiety. Thus, both types of attitudes—attitudes about one’s own computer use and attitudes about the impact of computers on society—contribute to computer anxieties.

With training, adult students’ attitudes about computers become more positive. That is, attitudes about one’s own interaction with computers and attitudes about the influence of computers on society at large generally become more positive as a result of instruction through computer courses in educational settings and of specific training in a variety of work settings.

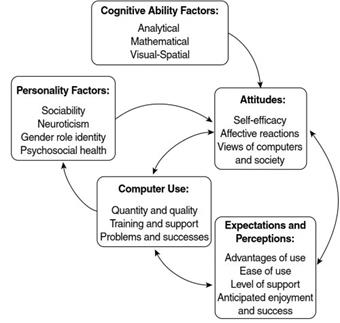

Figure 1. General model of individual differences in computer use

Figure 1 presents a general model of individual differences in computer use. The model indicates that attitudes are affected by personality and cognitive factors, and that they in turn can affect computer use either directly or by influencing values and expectations. The model also indicates that computer use can influence attitudes toward computers and personality factors such as loneliness.

Date added: 2024-03-07; views: 568;