The History of ancient Athens

Athens was the chief city in classical Greece, rivaling all others for political and cultural control. The city of Athens was in the region of Attica, three miles from the sea, and protected on three sides by the mountains, with the open sea to the south. To the northwest lay Mount Parnes, to the northeast Mount Pentelicus, to the southeast Mount Hymettus, and to the west, Mount Aegaleus.

These mountains ringed Athens and provided a natural defense. Closer to Athens to the northeast was Mount Lycabettus, and the rivers Illissus and Cephissus lay to the east and west, respectively. A further defense was Athens’s citadel, the Acropolis, a rocky hilltop that rose out of the Attica plain and formed a natural citadel. Two other smaller hills in Athens were the Areopagus, to the west of the Acropolis, and the Pynx, to the southwest.

Themistocles after the Persian War of 479 constructed the defensive walls with twelve gates; and from 461-456, the great Long Walls were built, connecting the city to Athens’s harbors the Piraeus and Phalerum. These walls were about four miles long, and when a third wall was built parallel to the Phaleric Wall (which now fell into disrepair), the area between the two walls was sufficient to protect all of Athens and allow the safe transport of goods to and from the harbors.

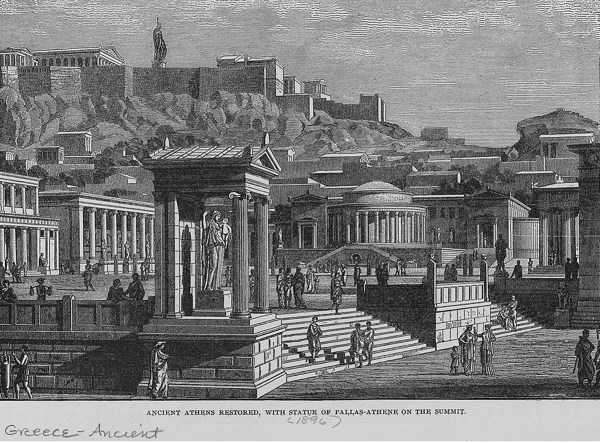

Restored version of ancient Athens. (From The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org)

This made Athens a virtual island, safe from any land attack. The walls were dismantled after the Peloponnesian War in 404 but were soon rebuilt in 394; by 200, they had become ruins. The two main gates in the city wall were the Dipylon, in the northwest, and the Sacred Gate to Eleusis, on the Sacred Way to the west. The Dipylon ran to the agora and Academy, and outside the wall were the principal tombs where Pericles gave his famous funeral oration.

Although the city and its environs were one of the most important in the Greek world, Attica did not ultimately control the political world of Greece. The city, however, did dominate and control its culture.

Inside the city lay several important regions that fostered commercial, political, and cultural developments. The old agora, constructed by the mythical king Theseus, was on the northern slope of the Acropolis. It contained the Eleusion, a temple to Demeter and Persephone that housed the sacred objects of the Eleusinian Mysteries once they were removed from Eleusis; and the Prytaneum, which housed the sacred hearth and the offices of the state where ambassadors were received. During the seventh century, this agora became too small, so a second and larger one was built, bounded by the Areopagus to the west and the Acropolis to the east.

Archaeological evidence shows that the Acropolis has been inhabited since 5000. During the Mycenaean period, a palace was constructed on the hilltop and walls were constructed by the late thirteenth century, supposedly during the time of Theseus. This synoecism, or amalgamation, of Attica into Athens was probably gradual, not a spontaneous or instantaneous event as recounted in the myth. While Athens did become the capital of Attica (Thucydides 2.15), it probably took at least a century to accomplish.

Nevertheless, Athens was strong enough to withstand the Dorian invasion, and it probably became a refuge for many of the surrounding Ionian states so they could help colonize the coast of western Asia Minor, or Ionia. During this period, they continued their unbroken line with the Mycenaean period during the Dark Ages. During the Archaic Age, Athens became an important city. The Mycenaean wall was no longer important and fell into disuse. The Peisistratids would build their palace on the Acropolis, but with their expulsion, it ceased to become the city’s fort.

The history of Athens was one of continual development and change. Like other Greek cities, it was originally ruled by kings, with the last one being the mythical Codrus, who fled Messenia during the Dorian invasion and went to Athens to become king. The Dorians invaded Attica, and according to legend, the city would be taken if the Dorians spared its king. Codrus, upon hearing this, entered the Dorian camp, picked a fight, and was killed; thereafter, the Dorians withdrew.

After Codrus, his son, Medon, became the first archon or chief magistrate and Athens’s government became representative. During the next few centuries, the powerful aristocratic families controlled the political, military, and religious offices of the city. Over this time, there were several attempts by individuals to break the power of the aristocrats, or oligarchs. One was Cylon in 632, who attempted to become a tyrant. He had married the daughter of the tyrant of nearby Megara and seized the Acropolis.

The Athenian archon Megacles besieged the citadel, forcing Cylon to flee. His supporters took refuge in the temple of Athena, but Megacles killed them, incurring a sacrilege or pollution on his family, the Alc- maeonidae, which was used as a political weapon against his descendants. A decade later, in 621, the lawgiver Draco attempted to break the power of the oligarchs. During a time of civil unrest, he was given the power to organize and write the laws, and lower-class citizens complained of this since they did not know what the laws were and they were constantly changing and hence hard to follow. The laws he wrote were viewed as harsh (hence the name Draconian), with even the most trivial offenses supposedly resulting in death. His laws were later repealed by Solon, except those concerning homicide.

A generation after Draco, the aristocrats still controlled the political system, and more hardships fell on the common Athenian. In 594, Solon was tasked with setting up a new system. He apparently got rid of debt servitude, an institution in which individuals were required to give one-sixth of their produce to the wealthy in return for seed and use of the ox or plow, but they could not leave their farms, becoming slaves to their creditors. It also appears that trade at this time potentially could hurt the Athenians, in particular the selling of grain outside Attica. This would have reduced the amount of grain available for the city and forced it to import even more.

Solon prohibited the selling of agricultural goods, except olives and oil, outside Attica. These goods were already important exports and would remain so. Rather, his plan was to prevent the sale of grain to Aegina and Megara, Athens’s enemies. The grain grown on the fields of Eleusis, although easier to sell in Aegina, was needed in Athens to feed its growing population. Solon’s most important law was the cancelling of debts, and all those who had been enslaved due to their debt were freed. Those who could not feed themselves and their families often sold themselves into slavery or became bond servants, but Solon forbade them from doing this anymore as a condition of their freedom. Solon realized the need for trade and promoted citizenship for those who settled in Athens.

In addition to these economic changes, Solon realized that the city’s government had to change as well. He changed the requirements to stand for office from birth to wealth. He changed the class systems so that there were four classes based upon annual income. Classes that harvested more than 500 bushels per year were called pentacosiomedimni; those that produced 300 to 500 bushels were known as hippeis; those between 200 and 300 bushels were called zeugitae; and those who produced less than that amount were called thetes .

Of the original three classes, the lowest had already existed and now the top class was added to them and but all were based on economics. In addition, he made the chief offices, archons, available through wealth rather than being limited to the original aristocratic family as had been the case for generations. The office was made available to those of the first class, and possibly the second since the zeugitae (third class) did not become eligible until 457. In addition, Solon allowed the thetes to be full members of the Assembly.

He also instituted the Heliaea, or people’s court, to try abuses of the magistrates’ power. Solon appears to have created the council of 400, where 100 members from each class or tribe were selected. This appears to have been the precursor to Cleisthenes’s council of 500. Solon had accomplished his changes through the current system of laws and politics, not as a tyrant. He had been elected archon and had been asked to solve the problems, which he did. He required everyone to swear that they would not change the laws until after ten years, and then he left office.

His reforms did not achieve the success he had hoped; soon party strife began again. After thirty years, the city fell under the rule of Pisistratus, who took advantage of the dissension between the old aristocratic party of the plains and the new group that supported Solon, mainly on the coast and in the mountains. The Athenians seized the island of Salamis and the port of Nisaea from Megara; the latter by Pisistratus, who supported and was supported by the extreme democrats. He became tyrant in 561, only to be pushed out about 556; around 550, he made himself tyrant again for a few months until he was exiled for the second time. Finally, in 540, he became tyrant for a third time and ruled until his death in 527.

Pisistratus confiscated some of the land of the aristocrats, his enemies, and used the land to redistribute to the poor, something Solon had refused to do. He instituted a land tax, equaling one-tenth of the produce, on these landowners and this became a source of revenue for his power. Pisistratus continued a policy of being friendly with the major states. He continued to have peaceful relations with Thebes and Thessaly, as well as Sparta and Argos, each the enemy of the other. He sent out colonies to the Propontis and worked to establish colonies and trading partners in the Black Sea region. An individual who led the capture of the Thracian Chersonese was Miltiades, a political rival, but he probably worked under Pisistratus’ authority.

Pisistratus also pushed the idea that Athena was the patron goddess or mother of the Ionian Greeks. This led him to assert control over Delos, and he purified the island by digging up the tombs in the sanctuary and moving them elsewhere. Most important, he reconstituted the Great Panathenaic festival, which was held every four years. In addition, he began the process of creating public works in Athens, which continued throughout its history.

With his death in 527, his eldest son, Hippias, took over. Helped by his younger brother, Hipparchus, Hippias continued his father’s work and even offered political reconciliation with the leading families. In 514, Hipparchus was assassinated, and Hippias began to rule harshly in retaliation for that, instilling fear in his subjects. In 510, Sparta advanced into Attica, and Hippias agreed to go into exile.

The people elected Cleisthenes in 509 to reform the constitution of Athens. His desire was to create a unified city where competition thrived but did not destroy the city due to regional differences and competing agendas. The first test of the new democracy was the war with Persia. In 499, Athens aided the Ionian cities in their rebellion against Persia. In 490, the Persians, led by the former tyrant Hippias, returned to Athens to punish the city for its interference.

During the previous several years, the Athenian democracy, aided by exiles who returned after the tyrant’s exile, especially Miltiades, had continued to build up the military. When the Persians arrived at Marathon, the Athenians with some allies from Plataea totaling about 10,000 defeated the larger Persian force.

The Persians retreated, and Greece prepared for the next wave. Ten years later, under Xerxes, king of Persia, the Athenians were faced with a more serious threat. Instead of a small expeditionary force, Persia came with a large army and navy. During the ten-year interval, the Athenians had fortunately found a new vein of silver in one of their mines, which provided the city with considerable money. Under their leader, Themistocles, the Athenians built a new fleet. After Xerxes stormed the Acropolis and burned the city, the Athenians and other Greek states rallied their fleet at Salamis, a small island off the coast of Attica.

Here, the numerous Persian ships were defeated in the narrows by the faster and more maneuverable Greek trireme. With Xerxes watching the battle, the Greeks defeated the Persians, who fled, leaving behind an army at Thebes. The following year, the Athenians joined the Spartans and other Greeks and defeated the Persians for good. Supposedly on the same day, the Athenian fleet defeated the Persian fleet at Mycale in Asia Minor, ending the Persian threat altogether.

After the Persian Wars, the Athenians embarked on several new initiatives. First, they accomplished their conception of democracy. During the fifth century, Athens filled most offices by lot, so all Athenians were capable of participating in the running of the city-state. This fulfillment did create potential problems, such as the rise of the demagogue who could sway the crowd with flattery, but the Athenians proudly held that their form of government ensured that all of the decisions of the state were made by the people.

The second initiative was the rise of Athenian culture, seen in the rebuilding of the Acropolis with new temples, especially the Parthenon. In addition, the cultural activities of the playwrights came into fullest flower with Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus. These were joined by the comic writers, especially Aristophanes. The playwrights produced a level of literary highlights that would not be seen again until the Renaissance.

The final initiative was the creation of the Athenian Empire, a naval empire built from the Delian League. During its eighty-year existence, the empire allowed Athens to finance its democracy and cultural activities. So long as Athens remained concentrated on the sea, it did not run afoul of Sparta, the land- based empire; but when Athens began to interfere in land-based activities, the two came to literal blows. The Peloponnesian War from 432-404 ultimately led to the destruction of the Athenian Empire. Throughout this time, the Athenian leader Pericles led Athens in its development of the empire, democracy, and culture.

After the destruction of the Athenian Empire, Athens continued to play a major role as a counterweight to the other major cities. Ultimately, like the rest of the Greek city-states, Athens could not move away from its individual concept of city power and unite to save Greece from the rise of Macedon. Under the leadership of Demosthenes, the Athenians fought with Thebes; they were defeated at Chaeronea, losing both their power and their independence.

Date added: 2024-08-06; views: 446;