The Bronze Age in Ancient Greece

The Bronze Age, or Early Helladic Age, began about 3000 and lasted until about 1000. On the mainland, the period can be divided into the Early (3200-2000), Middle (2000-1550), and Late Helladic (1550-1050) ages. On Crete, the period corresponds to the Early (3500-2100). Middle (2100-1600), and Late Minoan (1600-1100) ages, while on the Cycladic region or islands, it can be divided into Early (3000-2500), Middle (2500-2000), and Late (2000-1500) ages, which then merged into the Minoan period.

The Early Helladic period continued the Neolithic agricultural settlement patterns in the importation of bronze and copper, which could be used to make tools and weapons. The settlements tended to be on the Aegean coastlines in Boeotia and the Argolid or on nearby islands just off the coast, like Aegina.

The period further divided into three subperiods, corresponding to changes in society such as rapid expansion of metallurgy (subperiods 1 to 2) or a change in architecture and social status (subperiods 2 to 3), often accompanied by the destruction of some earlier sites. On Crete, the Early Minoan period saw the development of local areas of commerce and development of trades.

This then allowed local leaders to begin to exert more control over society, concentrating political power into the hands of a few, leading to monarchies. The Early Cycladic period saw the formation of villages on the islands, which could support only a few thousand each.

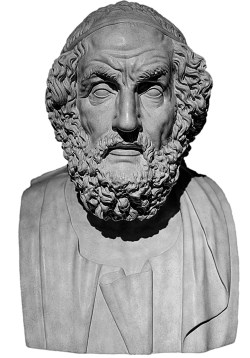

Bust of Homer, author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. (Lefteris Papaulakis/Dreamstime.com)

The Middle Helladic period often witnessed the move from coastal plains to hilltops, with the establishment of larger communities such as at Lerna. The period is characterized by Minyan wares (represented by pottery at Ochomenos, home of the legendary king Minyas), which when originally discovered were believed to be brought by invaders since it was not as sophisticated as the Early Helladic pottery. Excavations at various sites, however, have shown that the development of this type of pottery occurred naturally, without disruption from the Early Helladic and not the result of foreign invasion.

The pottery also seems to have been influenced by Cycladic and Minoan art. The site of Lerna shows a variety of grave types, including pits (merely holes in the ground), tholoi (which were more like chambers), cists (deep and rectangular, each with a mound or tumulus on top) and shafts (larger and deeper, rectangular graves about twelve feet deep, eighteen feet long, and twelve feet wide), where men and women were arranged on their sides (men on their right, women on their left) with their knees bent. These graves also had goods deposited in them.

The villages had single-story houses packed together, probably due to family affiliations and for protection. On Crete, the Middle Minoan period saw the first construction of palaces, which led to a segregation of duties and power. Around 1700, the first palaces were destroyed, perhaps by an earthquake.

The palaces were then rebuilt on a more grand scale, and more communities grew up across the island. This Neopalatial period, in the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries, witnessed the height of Minoan civilization. Minoan goods also began to be seen on the mainland at this time. It was then, in the Late Cycladic period, that the Minoan civilization overtook the Cycladic culture.

The Late Helladic period corresponds to the Mycenaean Age and is dated based on the change of pottery that developed during this period from Minoan and Cycladic influences. Mycenaean pottery occurred in Egypt from the eighteenth dynasty of Hatshepsut to Thutmose III. During the end of the Late Helladic period, the rise of large palaces at Thebes, Mycenae, and Sparta came about, with Mycenaean influence seen throughout the Aegean as related in the Iliad.

The Late Minoan period after 1600 and the eruption of Thera corresponded to the rise of the great palace at Cnossos. The Minoan centers continued for about two centuries before they were destroyed by an earthquake, from which they never fully recovered. Ultimately, the Mycenaean Greeks overran the Minoan palaces, which continued to be administrative centers until about 1200, when they finally fell.

The Mycenaean period has the most numerous archaeological remains and contain text written in the pre-Greek script Linear B, which provides some details on the social, political, and economic life of the Late Bronze Age kingdoms. Through excavations of grave sites at Mycenae, the full extent of artistic development has been shown. Other archaeological finds of pottery and sculpture also attest to the development of Greece culture during this period.

The excavation on Crete showed the independent evolution of Minoan culture during the Early and Middle Minoan (and Helladic) periods, with the creation of palaces, but after their destruction, the rise of large palaces such as at Cnossos in the Late Minoan showed further development. The Mycenaean takeover of Cnossos at the end of the Late Minoan and Helladic points to their continual expansion and influence.

About 1000, the Helladic period came to an end with the arrival of northern tribes that swept through the east. The name given to them varies from the Dorians in Greece to the Sea Peoples in the Near East and Egypt. They appear to have been part of a mass migration that came from the north and armed with superior weapons, made of iron.

The sites of Mycenae and Cnossos and others were conquered, and some, like Cnossos, were never rebuilt or reinhabited. The following period is one of chaos, out of which the Greek homeland saw an increase in population and a rise of local kingdoms centered on numerous small city-states rather than the great overlords of the Bronze Age.

Date added: 2024-08-06; views: 399;