Architecture of Ancient Greece

The monument architecture seen in Greece has its origins in the architecture of Egypt and the Near East. These structures and the influence of monument design arrived in Greece via Crete and the Minoans. Through Minoan contact with Egypt and the Near East, the architectural types and designs arrived in Crete and can be seen in the monumental palaces, such as the one at Cnossos.

Here, the modular complex without defensive walls, on a hill facing the sea, had a large, open palace courtyard surrounded by royal apartments, state rooms, and throne rooms, which are mainly colonnaded as in Egyptian architecture, offering entrance through numerous points.

Unlike in Egypt and the Near East, many of the monumental architecture in Crete was also civic in nature. Although most of the Greek architectural remains are temples, usually classified as religious rather than civic, they were part of an elaborate complex of religious, civic, and open spaces.

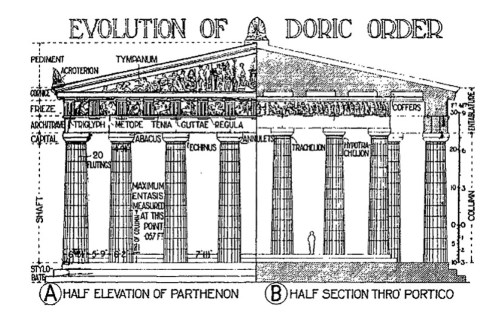

Parts of Doric temple architecture. (Sir Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method for Students, Craftsmen, and Amateurs. London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1924)

The difference between the light, airy, and open structures of Crete contrast with the massive stone construction of Mycenae. The open courtyard of Cnossos gave way to the megaron, with its monumental form of a homestead with a central hearth and access through a single entrance or doorway. The approach is axial from the medium-sized courtyard through a columned porch and vestibule, which differed from the open-sided style at Cnossos. Here, the flow is linear and symmetrical.

This difference from Cretan architecture also can be seen in the creation of the great beehive or vaulted tombs of the fifteenth to fourteenth centuries, best seen at Mycenae in the Treasury of Atreus, with its entrance cut into a side of low hill and faced with massive stone walls leading to a doorway with a relieving triangle on top to shift the weight from the door lintel to the sides of the tomb to keep from breaking the lintel due to pressure, and a soaring vault, an architectural type not seen again until the Roman Empire 1,500 years later. When the Dorians swept away the Myceneans, this engineering feat was lost to future Greeks.

Greek architecture had its basic form in the megaron, a rectangular structure with a porch along the facade before the entrance, and a pitched gable roof. It had existed for centuries, found at Troy about 2700 and in Mycenaean cities and palaces. The Mycenean megaron was centered on four columns set in a square shape to support the open space in the center. By the end of the Dark Ages, the general appearance of Greek architecture had begun to take shape.

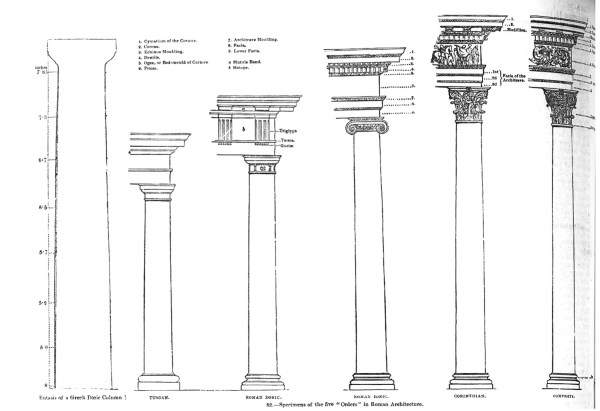

Ancient Greek orders

The megaron then became larger and was made of stone instead of wood. At the same time, the roof was extended, often around all four sides, to create a deeper porch so that the colonnade extended around the entire structure. These in turn allowed for more developments for temples producing the straight-lined Doric order, the less massive and more graceful Ionic order of Asia Minor, or the merging of the two orders creating the Corinthian order in the fifth century, probably at Corinth.

The siting of buildings was also important in the development of civic architecture. It was important for a visitor to see at least two sides of a building or temple in order to comprehend its size and function. This included making the columns at the ends thicker than in the central part of the colonnade to highlight regularity so that the light would produce the illusion of all the columns being regular. This also featured columns that taper at the top and swell in the middle or entasis to create the illusion that the columns were in fact the same size. This allowed the structure to appear homogeneous and straight.

Greek architecture can be seen in a variety of forms and styles. The Greeks were known for their precision and high-quality creations. Their forms of perspective and use of formulas became standard throughout the Mediterranean. The main development was in the post and lintel, with vertical posts supporting a horizontal lintel. The fundamental component of Greek architecture was the column, which during the Archaic and Classical periods were represented by the Doric and Ionic capitals.

In the late Classical and into the Hellenistic ages, the Corinthian capital became common. Solid stone drums rested on top of each other to form a vertical column. The columns were wider at the bottom and then became narrower at the top, but they had an outward or convex curve (bulge) or entasis, which gave the appearance to correct the optical illusion that the columns became concave. At the top was the capital, which was convex in the Doric order while scrolling out in the Ionic and concave in the Corinthian.

Doric columns had no base, and the columns were fluted. The capitals had two parts, a flat slab called an abacus that was wider than the column to support the beams, and a plain echinus or molding, a cushion-like slab. The entablature, a horizontal continuous lintel, rested on top of the capital and was composed of three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. The architrave was usually plain, with the exception of a small band that has pegs attached to them called guttae.

The frieze has stone slabs of alternating series of triglyphs, a tablet with three vertical bars or groves, and metopes, square spaces between the triglyphs, often decorated with relief sculptures. At either end of the building was the pediment, often decorated with sculptures. Like the triglyphs and metopes, the pediment had reliefs, which later had sculptures in the round. These triangular pediments were enclosed by gables.

Ionic columns had bases to support them that had more vertical flutes than the Doric columns. The Ionic capital has two volutes (also called scrolls), spiral scrolllike ornaments that rested on a band of palm leaf ornaments. The abacus became narrow, and the entablature was now just three horizontal bands, and the echinus was fluted. What became more important in the Ionic order was the frieze, which became a sculptural relief running around the whole building, a continuous scene that usually told a story.

The third order, the Corinthian, had capitals with bell-shaped echinus and were richly decorated with acanthus leaves, spirals, and palmettes. In addition, on each corner was a pair of volutes so that from any side, the same image was presented. From the remains, the Doric order was more prevalent on the mainland and southern Italy. The Ionic order was found more on the Aegean islands and in Asia Minor.

The temple became the most common type of architectural form in the Greek world, with many examples found, especially in what is now southern Italy and Sicily. These temples were usually oblong, with a series of columns around the building, and they held cult statues meant to protect the cities.

The original temples were most likely constructed of wood, and later some were made of stone as well. Although most of the largest temples in antiquity were probably 150 feet long, some, like the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, were 300 feet long.

The general structure of the Doric order, especially temples, featured the stepped platform, which had the stylobate, or the floor of the temple on which the columns were placed, on top. The columns with grooves or flutings supported the capital, which had the echinus or molding around the abacus, which supported the entablature. The first part of the entablature was the architrave, or a horizontal beam supported by the columns.

On top of this was a small ribbon or taenia of molding. It was on this that the frieze sat, made up of triglyphs and metopes. The triglyphs, three vertical bands, had under them the regula, a fillet, and gutta, which probably were used to repel water so that it would run off. In between the triglyphs was the frieze or metope. On top of this was the cornice, a horizontal decorative molding that crowned the entablature and encased the entablature.

Below the cornice was the mutules, square blocks aligned with the triglyphs, which harkened to earlier times, when the structure was made of wood, and this is where the wooden rafters were held in place by pegs. Above the cornice was a pediment supporting the roof, and on its edge was the sima, an upturned edge that formed a gutter that fed into downspouts. Above the door and window was the tympanum, a semicircular sculpture.

On the far edge and corner of the pediment was the acroterion, an ornamental ornament that could be a statue or simple acanthus. Across the span of the structure was the roof, which was often supported in the interior of the structure with more columns. Originally, the structures would be made of thatch, but with the rise of stone, ceramic tiles were used.

The Ionic order had a large base on which the slender, fluted columns rose. On its capital, two opposed volutes are in the echinus. Unlike the plain echinus of the Doric order, the Ionic order has an egg-and-dart motif. Typically, the height was nine times its diameter at the base. Whereas the Doric order column had twenty flutes, the Ionic order column had twenty-four.

During the Classical period beginning in 447, the construction of the great building in Athens was under the direction of Pheidias and the general planning of Pericles. The Classical Age gave rise to the theoretical concept of beauty, and it was seen in the areas of architecture with the development of proportion and order.

In addition to temples, other Greek architectural structures include stadiums, theaters, and propylaea (gates). The stadium, oblong and oval, encouraged the development of athleticism. Located on the outskirts of cities, these structures were used during the great festivals. The stadium often had a bank of seats rising along the long, straight sides. The long sides would be open at one end, while the other end had a curve.

Another Greek architectural structure was the theater, a half-circle cut into the side of a hill with seats rising upward, with a stage at the bottom. Theaters were built throughout the Greek world and allowed the union of civic and religious functions since many of the theatrical productions took place during religious festivals.

Still another Greek structure was the propylaea or gate. The great Propylaea on the Acropolis is one of the best examples of aligning religious and civic functions. The Propylaea followed the Ionic order in order to support a higher roof than Doric columns could attain.

The Propylaea provided a monumental entrance to the Acropolis on its western side. As a gate, it would also act as security. Since the entrance was not only for people but also for sacrificial animals, a sloping roadway in addition to steps was created. To accomplish this, the architect had the entrance on a lower level on the east and an exit on a higher level on the east. To ensure a graceful design, the roadway became the central axis with the west entrance, with two other entrances with steps for pedestrians.

The Propylaea also included two porticoes, as well as a picture gallery. It was built just prior to the Peloponnesian War (437-432), and its construction was interrupted by the war (it lacks two planned audience halls and was never completed).

Some other Greek unusual buildings include the Tholoi, or circular structures. Their design and purpose are not always known. It is possible that they derived from the early circular huts or to covers of a sacred hearth. In Athens, the Tiolos in the Agora was the official dining room for the chairmen of the Boule. The Tholoi at Epidaurus and Delphi are extremely refined buildings.

The Tholos at Epidaurus was built by Polykleitos the Younger in the early fourth century, who also constructed the theater at Epidaurus. The Tholos had two colonnades, an outer Doric and an inner Corinthian. The Tholos at Delphi is often associated with the priestess of the Oracle. Another unusual architectural structure was the tomb of Mausolus of Halicarnassus, which was 150 feet high with a pyramidal roof.

The evolution of Greek architecture allowed the further development of civic and religious life. The religious structures soon spread throughout the Greek world and became prominent in the Classical Age, when the union of civic and religious functions can best be seen at Athens. The new structures promoted the glory of Athens and its empire.

Date added: 2024-07-23; views: 559;