Images on Sarcophagi in Ancient Rome

Just as, in the most distressful times, Roman emperors put 'Peace' or 'Concord' on their coins, so wistful glances were cast at the gracious round of country pursuits and these, rather than scenes of tribulation, became in time a favourite choice for the decoration of sarcophagi. The work of plucking or treading grapes, with its Bacchic overtones, was especially popular. The usual formula runs, with slight variations, along these lines: in the foreground husbandmen, or naked genii, cheerfully trample grapes in a tub ornamented with a lion's head, as though in sombre reminder that, even amid the happiest occupations, danger lurks.

The owner of the vineyard, standing beneath the roof of a farm building, surveys the lively prospect; to the left someone on a ladder is picking grapes while, opposite, two men carry away a basket of grapes under the guidance of a third. This vine-treading motif gained ready acceptance in Christian circles where passages such as T am the true Vine' were well known. A splendid, if close-packed, sarcophagus, now shown in the Vatican, combines it with no less than three representations of the Good Shepherd, one bearded and two without a beard.

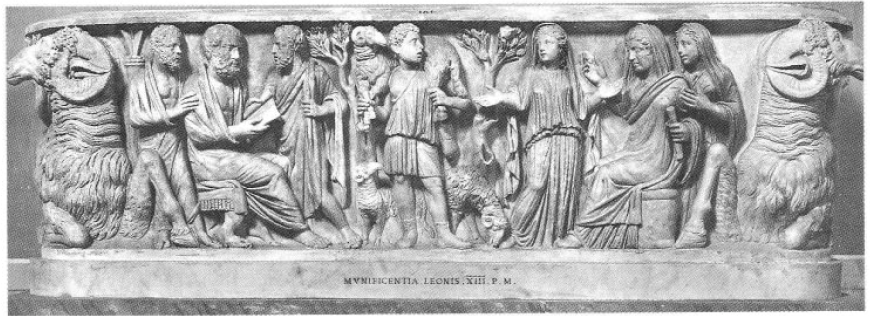

The god Dionysus can also appear, in Greek tradition, either as a mature, bearded man or as a graceful youth, and it seems that Christians happily absorbed into their art traces of his imagery. The entire front surface of the Three Shepherds sarcophagus (fig. 31), carved in marble of the finest quality and excellently preserved, is packed with the typically Bacchic figures of gay little winged cupids picking the grapes, carrying bunches away in baskets and trampling them vigorously in a tub. At one corner, however, the emblem of exuberant life, in this world and the next, is not wine but milk, the natural drink-offering of a pastoral people.

Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 191A: the Three Shepherds

In Aeschylus' tragedy The Persians, sweet white milk is one of the propitiatory gifts made to the departed, and, in Christian symbolism, milk, taken in connection with the Good Shepherd as the life-giving sustenance of lambs, implies the sacrament of the Eucharist. It was therefore not surprising that St Perpetua, shortly before her martyrdom at Carthage, had a vision in which 'a man with white hair and a shepherd’s tunic engaged in milking his sheep' offered her a morsel of curdled milk which she received with hands clasped together and ate rejoicing to find in her mouth a taste of great sweetness. On the Three Shepherds sarcophagus, then, the symbols of milk and wine combine in a scene of lush growth and vital energy. No wonder that a spectator, seated under one of the vines, raises his right hand in thankfulness while, with his left, he clasps the bowl into which an attendant is about to pour his share of the produce.

Another theme taken over without the slightest scruple was that of the contemplative philosopher, and here again the Christians adapted current practice to their needs. For the figure of the philosopher, representing education in its highest and purest form, seems to have derived originally from the influence of the Neoplatonists, whose leader Plotinus was teaching in Rome between 244 and 270 ad, though in Christian hands the philosopher is, of course, the teacher who finds his answer to the mystery of life in the scroll of the Gospels.

Christ may indeed be shown as the typical Cynic philosopher with long beard and dishevelled hair, a broad, almost naked, torso, and highly-strung, expectant gaze—the whole portrait is closer to fanaticism than to anything like sophistication.4 Usually, however, the Christian philosopher is more confident and composed because he knows the answer to the really important questions, and one attractive group of early Christian sarcophagi readily combines the symbolic types of philosopher, Good Shepherd and Owns.

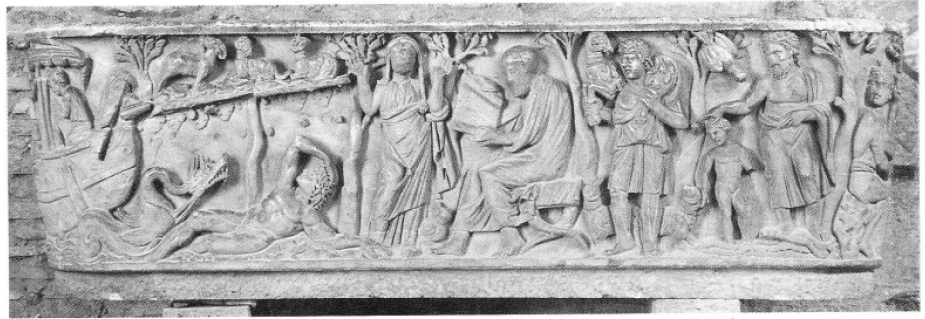

The best example of this combined theme is a sarcophagus found near the Via Salaria and now exhibited in the Vatican collection (181: fig. 32). Within a frame bounded by two vast rams' heads, the figures are arranged with a classic, harmonious sense of form. On the left sits the grave and bearded philosopher, clasping his book which contains, as his expression indicates, 'all we know and all we need to know'. Two companions press close to the philosopher in an attempt to learn his secrets. At the other end of the sarcophagus, another group of three persons precisely balances the philosopher and his friends. Here it is a woman, also seated between two attendants, who clasps the scroll of divine learning with one hand while the other is raised in a gesture of prayer.

32. Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 181: Philosopher, Oraus and Good Shepherd

The attendant maidens are not, however, looking at her: one is turning away, with hands outstretched, in the typical posture of the Orans, and both have their gaze riveted on the central figure of the composition, a young, curly-haired shepherd, standing between two rams and holding a third over his shoulders as he turns to face the suppliant women. The whole composition, dignified and well-spaced, is a concise sermon to the effect that true wisdom consists in turning to Christ as the guarantee of safety.

Philosopher, Orans and Good Shepherd continue for many years as symbols of true wisdom, faith and salvation, although, by the end of the third century, they tend to be overwhelmed by a riot of detail drawn from incidents in Biblical history. The carving is, however, still disciplined and orderly on the celebrated sarcophagus in the church of S. Maria Antiqua, in the Roman Forum (fig. 33). This sarcophagus is of an elongated tub-shape, with the narrative sculpture continued round the two ends but not at the back. The first scene is an elaborate version of the story of Jonah: Neptune seated, then the boat with two men in it, and finally Jonah lying in an attitude of graceful repose under his gourd tree, with the horrific monster, looking singularly unlike a whale, extended in all its menace nearby.

33. Rome: Sarcophagus of S. Maria Antiqua

The top of the tree is flattened to form a second register of carving, in which three horned rams appear. After the Jonah scene comes the Orans, standing between two trees and having a bird with upturned head near her feet: the whole composition is thus rich in allusions to Paradise. The philosopher is shown next, seated on a cross-legged stool and holding an open scroll. He is followed by a Good Shepherd of the 'young countryman' type and, immediately afterwards, by a Baptism scene. Here the Baptist, large and bearded, with his garment hanging loosely from his left shoulder, contrasts with the diminutive, boyish figure of Christ, who links this scene with the Good Shepherd motif by stretching out his right hand to touch one of the sheep. Finally two fruitpickers are shown, one sitting, one standing, beneath the trees from which they are filling their basket. The subjects of the Maria Antiqua sarcophagus may be conventional, but they are rendered in a manner which indicates high artistic imagination as well as technical skill.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 759;