Christian Images on Sarcophagi. Image of Jonah

As a theme chosen to illustrate the benevolent and effective power of God, the story of Jonah became a firm favourite, even though the manner of showing his escape from peril is odd. It might be expected that the casting up of Jonah onto the seashore would be the incident most commonly shown, particularly as this is understood by St Matthew as a sign of the Resurrection; but in fact this part of the story is far less often depicted than Jonah beneath his gourd tree. And even here the Bible account is not followed very closely.

So far from appearing as a prophet angrily awaiting the destruction of Nineveh, Jonah is represented as lying, naked and carefree, in complete repose. Two influences may be at work here. Jewish legend recorded that Jonah's clothes were burnt inside the whale which threw him up on the shore weak as a newborn baby, whereat God graciously allowed a tree to grow up and shade him from the elements.

Perhaps more important as an influence on Christian art is the Greek story of Endymion, the beautiful youth beloved of the Moon, to whom Zeus granted the blessing of long-lasting slumber in perfect contentment. A pagan sarcophagus in the Museo Nazionale at Naples shows Endymion lying asleep in graceful felicity, and there are other parallels to the Christian artform, such as an Italian terracotta, now' in the Louvre, on w'hich Dionysus appears naked and sleeping beneath a vine. Jonah is in fact a symbol less of the final resurrection than of that sojourn of the departed in regions w'here, under the divine protection, they peacefully await the last trump. In pace, therefore, 'in peace', is the epitaph attached to the Jonah scene which forms the frieze on a Vatican sarcophagus commemorating 'Exuperantia, a very dear daughter'.

During the confusions and failures of nerve W'hich marked the latter part of the third century, pagan sarcophagi reverted to a chaste simplicity of classical forms. A typical example, from the church of S. Sebastiano, has slim pilasters at the end, followed by a series of seventeen vertical channels on each side of a circular frame containing realistic portraits of a husband and wife. But the expression on the faces shows a melancholy characteristic of this period when Roman culture seemed to be breaking down: the eyes stare upwards into nothingness, the lips are tight set in despairing resolution.

By contrast the Christians, while not blind to contemporary disasters, were inclined to view them as signs that the world was drawing to its end. A crisis of this nature provoked not pessimism but a confident trust in the God who controlled the end of things no less than their beginning, and the ground for that trust was provided by the incidents, demonstrating the divine power, which were recorded in Holy Scripture. The decoration of the sarcophagi therefore marks a certain change from hints and symbols to the open, literal proclamation of Biblical scenes. In the excitement at all this, some of the earlier restraint and dignity is lost, and the surface of the coffins frequently becomes over-crowded.

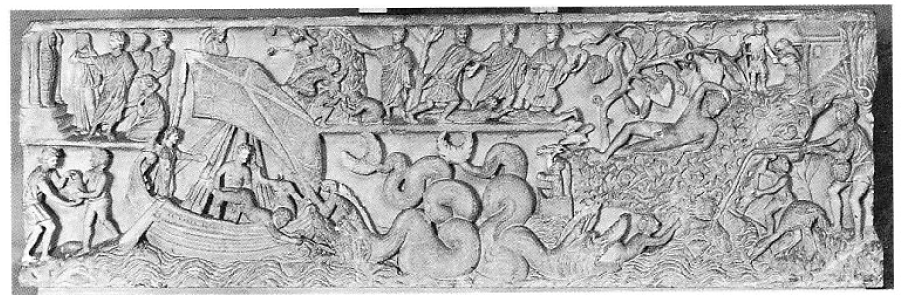

This change is illustrated by the most famous of the 'Jonah sarcophagi', Vatican 119 (fig. 34). The entire surface of the front, considerably restored, is covered with sculpture, but vigour and a sense of rhythm prevent the detail from becoming tedious. The middle of the scene is occupied by two enormous whales, of almost identical size and shape. While their bodies coil in parallel curves, their heads are turned in opposite directions. The creature on the left opens its mouth to receive Jonah, who is hurled from a sailing-ship into the sea by three members of the crew. His hands are stretched out in what appears an attitude of supplication, and his gesture is precisely the same when he is vomited forth, by the whale in the right of the picture, onto the shore.

Here are reeds and bushes, rendered in a somewhat impressionistic manner by deep use of the drill, as well as a heron, a crab, two snails and a lizard. An angler, with his basket on his arm and assisted by a small boy, is in the act of drawing a fish out of the water; above, a shepherd tends his beasts in front of a sheepfold of elaborate workmanship. Nearby, Jonah appears for the third time, under a gourd tree depicted with accuracy and much artistic skill. Sleeping in his conventional attitude of perfect composure, he is, perhaps, the little fish hooked by the Angler as he swims in the waters of baptism, in any case one of the sheep whom the Good Shepherd guards in his heavenly mansion. He is, moreover, contained in the ark of salvation, typified by Noah floating in a tiny chest by the side of the whale.

Here the story of Jonah has been worked out with an assured delicacy and invention along the lines of a recognized formula. But the artist was not content merely with his cycle of Jonah scenes. The upper part of the sarcophagus is marked off bv a horizontal boundary-line which supports three Biblical illustrations, though the predominance of the Jonah motif is such that it intrudes into the space assigned to this top register. The first of the events is difficult to interpret: three men are rushing hastily away to the right and, in doing so, trample on two others who have fallen down. The meaning is obscure, but among the guesses which have been made at it are Lot's flight from Sodom and the arrest of St Peter. In the centre stands the dignified figure of Moses, who, with his wand, strikes the rock from which the thirsty Israelites eagerly drink the water assuring them of life.

Some maintain that the figure is really that of St Peter, the counterpart of Moses in the New Covenant, who refreshes the Gentiles with the waters of true and saving doctrine. Whether the figure be Moses or Peter, his action illustrates the principle laid down by Hermas, the second-century prophet, in one of his visions: 'Your life was saved and shall be saved through water.' At the left-hand side, amid a group of astonished onlookers, Christ stands in a similar attitude of benevolent power as, with hand outstretched, he summons Lazarus to 'leave his charnel-cave'.

The raising of Lazarus, which provided a secure Biblical foundation for the doctrine of the resurrection of the flesh, became, from the end of the third century, a subject frequently presented on the sarcophagi in a classic pattern. An early example, carved before restrained formality had given place to an exuberant medley of small, jostling figures, is provided by a child's sarcophagus now preserved in the Capitoline Museum at Rome. The front surface of the coffin is divided by vertical lines into five panels of unequal size. The two end-panels show the father in philosopher's costume and the mother as an Orans.

The central panel contains the boy's portrait within a circle having two birds above and a pastoral scene, with tree, shepherd, and sheep below, while the two large intermediate panels offer their message of hope. That on the right side shows the philosopher seated and clasping his copy of the Gospels, from which he reads to an attentive, eager group of two men and two women. This philosopher has about him no air of the frenzied prophet or half-naked Cynic: the pallium with which he is clothed hangs in dignified fashion and there are sandals on his feet. He is in fact the type and exemplar of one who teaches meaningful truth.

With almost exactly the same appearance and clothing Christ appears, on the left side, standing with two companions before a little shrine that has two columns supporting a triangular pediment. At the top of four steps within the entrance of this formalized tomb is set the figure of Lazarus swathed from head to foot in burial garments. Christ, retaining the roll of the Gospels in his left hand, stretches out his right hand which clasps the miracle-worker's wand. The word of philosophic wisdom is thus ratified by an act of majesty and power which serves for the bereaved as a heartening precedent.

Another comforting episode that frequently recurs is the Multiplication of the Loaves, where the Feeding of the Five Thousand, reduced to a convenient shorthand summary with no more than two or three persons present, hints at the Eucharist. Thus emphasis is given not only to the idea of the true philosophy bringing light, but also to the concept of sacraments as unfailing spiritual nourishment.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 631;