Statuary. First Centuries of the Christian Church

By contrast with the abundance of sarcophagi, examples of statues carved in the round during the early centuries of the Christian Church are very rare. Both the Mosaic condemnation of graven images and a general desire to separate themselves from pagan associations led such third-centurv Fathers as Origen to blame those who 'fix their gaze on the evil handiwork of sculptors'. Even when peace was restored to the Church and Constantine, an impassioned collector of statues, presented fine examples not only to his new capital city but also to the various churches which enjoyed his patronage, the growing desire for splendour was, in general, satisfied rather by painting and mosaic than by statuary.

Writing in about the year 310, Eusebius notes that in his day one might see at Caesarea Philippi two bronze figures carved in relief, of the woman with the issue of blood crouching before Jesus 'clothed in comely fashion in a double cloak'. Whether Eusebius was correct in his interpretation cannot now be determined; it was not unknown, in later periods, for pagan statues to be Christianized and to be stamped, in confirmation, with the sign of the cross.

The marble statue of a philosopher, seated in an attitude of calm authority, was found at Rome in 1551 and is now in the Museo Pio Cristiano. Head and hands are missing but the pose of the figure and the manner in which the draperies are executed point to a skilled craftsman. One side of the philosopher's chair is engraved with a list of writings attributed to Hippolytus, a scholarly controversialist exiled from Rome in 235, while the other side offers tables for calculating the date of Easter such as were contained in Hippolytus' treatise 'On the Pascha'. The excellence of the carving has led some observers to doubt whether the statue could have been produced in Christian circles in the first half of the third century, and to suggest that it may have been the product of a pagan workshop and adapted in commemoration of Hippolytus.

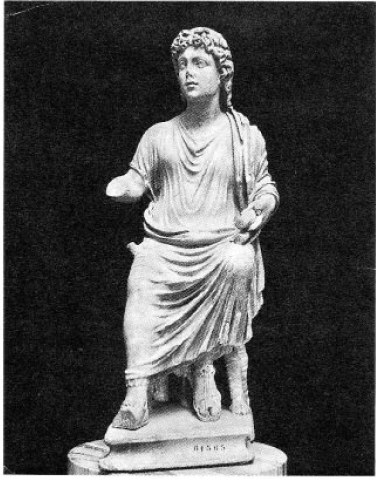

An attractive marble figure, of unknown provenance but now in the Museo Nazionale at Rome, has commonly been described as 'Christ teaching his followers' (fig. 47). The young man, enveloped in drapery and seated with one knee raised, holds a scroll in his left hand; but the soft, effeminate lines and luxuriant coiffure explain the title by which the statue was originally known: 'seated poetess'.

47. Rome, Museo Nazionale. Statuette 61565: Christ teaching

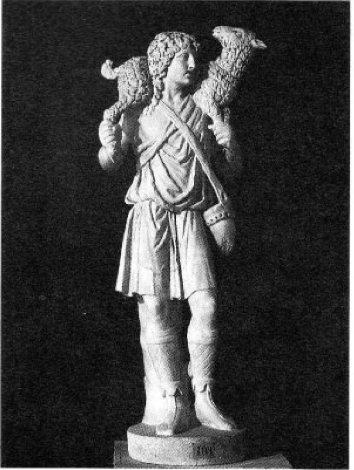

The touches of romantic idealism would accord with a second-century date and thus make identification with Christ extremely doubtful. But, although the third century, with its frequent upheavals, set a fashion for artefacts of a rougher and harsher nature, the old ideals and art- forms maintained their hold in aristocratic as well as in religious circles. The boy-Christ shown on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus and the curly-haired Christ of the Passion-sarcophagus (174) display an easy grace amply charged with sentiment, and one may assign to the same period of manufacture, roughly 360 ad, the 'seated poetess', accepted as Christ teaching his disciples.’ Similar in feeling is the marble statue of a youthful shepherd, also of unknown origin but now in the Vatican Museum (fig. 48).

48. Rome, Vatican Museum: sculpture of the youthful Good Shepherd

Clad in the rustic exomis, a sleeveless tunic, and with purse slung over his right shoulder, he clasps with both hands the sheep which he bears across his back. In the treatment of the eye, with the pupil slightly off centre in order to emphasize the reflective upward glance, may be recognized, with reference to the sarcophagi, a device typical of the middle of the fourth century. Statuettes of the Good Shepherd may have been thought useful in protecting houses from misfortune, for several other examples have come to light. A rough and homely specimen, unearthed at Corinth, is now in the Byzantine Museum at Athens, while another diminutive example, skilfully carved in bone, has found its way to the Louvre. The Cleveland Museum of Art also contains just such a statuette (fig. 49).

49. Cleveland, Museum of Art: sculpture of the mature Jonah Good Shepherd

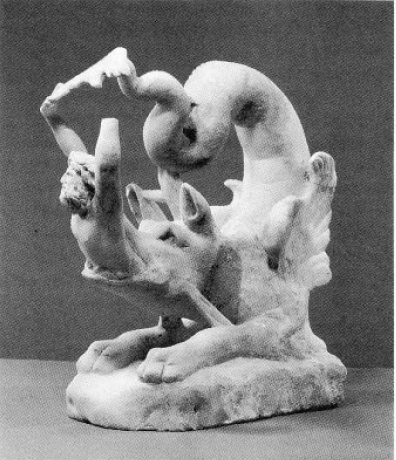

Another sign of prayer or thanksgiving for deliverance from peril seems to have been provided by marble statuettes, of eastern Mediterranean origin, showing Jonah's escape from the whale. One set of these, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, is associated with a group of male and female portrait-busts which, by reason of clothing and hairstyle, point to a date near 285 ad. The Jonah figures represent a type of garden ornament favoured by wealthy pagan families, and it seems strange that themes of Christian interest should be incorporated, in defiance of official policy, into a form of luxurious decoration more commonly exemplified by Orpheus.

The statuettes, though considered by some not to be genuine early Christian artefacts, may nevertheless be seen as refined essays in the tradition of Hellenistic baroque. Jonah is shown as a mature man with full beard and mop of hair. The most dramatic of the figures presents a rhythmical, circular shape with the tail of an exceptionally sinuous whale curving over almost to touch Jonah's head as he emerges from its mouth (fig. 50).

50. Cleveland, Museum of Art. Marble statuette: escaping from the whale

The bronze statue of St Peter, majestically enthroned with the key of authority in his hand, which is one of the attractions of St Peter's in Rome, is now firmly ascribed to the thirteenth century rather than the fourth, though its posture was probably suggested by a seated figure, carved from polychrome marble but extensively restored, in the Vatican Grottoes.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 625;