Sarcophagi after Constantine. The third part

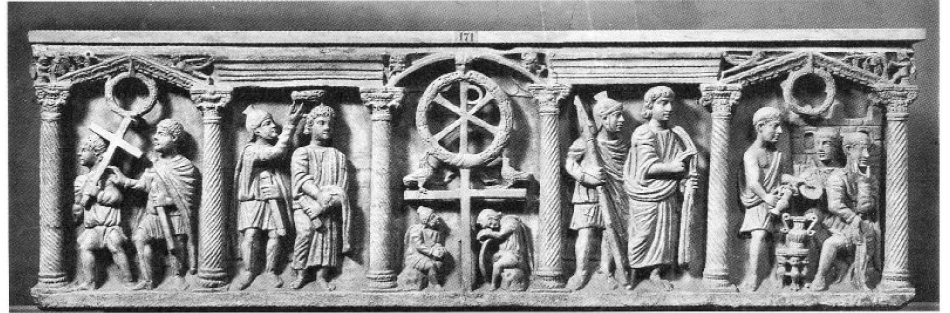

Following this line of argument, scenes from the Passion of Christ become valuable emblems of hope and confidence. The earliest Passion-sarcophagus is a splendidly designed example, worked in pinkish marble, now in the Vatican collection (fig. 40). The front is divided by an elaborate architectural arrangement of columns and entablature into five panels. On the right side a helmeted soldier leads the youthful Christ along as prisoner, while Pilate, supported by his legal assessor, sits in front of his city prepared to wash his hands in token of guiltlessness. To the left, a soldier crowns Christ with a laurel wreath while another soldier forces Simon of Cyrene to bear the cross uphill to Golgotha.

40. Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 171: a Passion-Sarcophagus

These realistic scenes are summed up, or commented on, in the symbolic language of the centre panel, surmounted by little faces representing sun and moon as if to emphasize that the matter is of worldwide and lasting importance. Within the panel stands a simple cross; beneath its arms two soldiers crouch, one fast asleep, the other numbed and bemused, as though in the presence of a miraculous resurrection. This much might be viewed as a continuation of the plain narrative, but over the summit of the cross a laurel crown, enclosing the chi-rho monogram, hangs from the beak of an eagle while two doves peck at the berries.

Just as the victorious general on the field of battle received the unfading crown of laurel as a sign of his triumphant prowess, so here the theme of the unconquerable cross works itself firmly into the midst of the Passion scenes. In accordance with this, Christ is shown not in terms of the agonized realism that became fashionable in the Middle Ages, but as the youthful hero, attractive and composed in face of inevitable destiny.

A few years later, in the middle of the fourth century, the idea that the Passion of Christ was an earthshaking triumph receives its proper development as a teaching and a trust handed over to the Church. On a vast sarcophagus in the Vatican Grottoes (174) scenes from the Passion are repeated within a regular framework of columns decorated with a wealth of abundant detail which suggests that the craftsmen were of Asiatic origin. To the left, the sacrifice of Isaac serves as Old Testament commentary, while the arrest of St Peter hints that those who continue the life of the Church may not hope to escape their share of redemptive suffering.

In this respect they present a contrast with Pilate who, on the right side of the sarcophagus, looks not at the graceful figure standing before him but straight ahead as he dips his fingers into the bowl of water which might be hoped to relieve him of responsibility. Meanwhile, at the centre of the drama, there is no veiled symbol of cross and laurel crown but Christ himself enthroned in gracious majesty above the submissive, obedient figure of Earth. Two apostles reverently attend him as, with right hand upheld in blessing, he extends with the other hand his scroll of authority towards the crouching, half-bowed form of Peter.

The fashion of decorating tombs with the figure of Christ in triumph developed along several distinct lines, but a common factor is a frame or background of architectural motifs and the presence of apostles, both themes having some connection with the political propaganda of the civil power, as illustrated on the Arch of Constantine.

Following this style of presentation, Christ is portrayed as dominant before the columns and arches of a heavenly city and flanked by the company chosen to bear his words to the ends of the earth. While this Christ is usually shown as the pattern of youthful comeliness, he may also appear in the form of a venerable, bearded figure, resembling the Zeus or Asclepius of pagan mythology, and dispensing to his eager yet awed apostles the scroll of the Law which, as the Ancient of Days, he promulgates for all time. A scene of this kind is clear enough in itself and additional commentary, however edifying, is hardly necessary. It is nevertheless sometimes provided, as when, on a fragmentary sarcophagus in the church of St Sebastian, the lambs of sacrifice, one bearing a cross on its head, crowd around the Master's feet.

The architectural theme, developed in such a way that it displays a line of recesses in the wall of a fortified city, is characteristic of a group known as the City-gate sarcophagi. One example, now' in the Louvre, shows this particular background with, before it, the Ascension of Elijah, as this event is recounted in the Second Book of Kings. Below the hooves of the four prancing horses that bear Elijah aloft is shown a river-god, presumably Jordan, holding a long reed and portrayed in the conventional manner found in first-century wall-painting from Pompeii. This river-god seems to be acclaiming Elijah while, nearby, Moses appears receiving the Law from the hand of God, on Mount Sinai.

Almost exactly the same type of city-gate background, with its arches, windows and battlements, is used on a large sarcophagus of Asiatic type and distinctly 'ecclesiastical' tone, found in the Vatican area but later transferred to the Louvre. The whole of the front surface is devoted to a single scene, that of Christ delivering his Law to the apostles. Christ stands bearded and majestic on a rock, his unique power emphasized by the elaborate patterning of capitals and pediment which frame his head and shoulders. On each side are ranged six apostles, uniformly clothed in their ample robes but so grouped—one, two, three on the left side; one, three, two on the right—as to avoid dullness or excessive rigidity. At Christ's feet two diminutive attendants crouch as, from his position head and shoulders above the apostles, he dispenses the scroll of his teaching to Peter, who advances bearing a jewelled cross on his shoulder. It would scarcely be possible to demonstrate more clearly the idea of celestial authority, standing over against the transitory might of the civil power.

A variant on the victory theme, and one that adheres more closely to that earlier style which emphasized the miracles of healing, is provided by those sarcophagi which make a particular feature of Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem. This scene is found, on one of the Vatican examples, with Adam and Eve at one end of the composition and Lazarus raised from the tomb at the other end, while a more crowded and elaborate manner of stressing the same lesson is provided bv the sarcophagi of the so-called Bethesda group.

A typical example, again in the Vatican collection, shows a rather mixed architectural background of gateways and pedimented columns before which occur the healings of the two blind men and the woman with the issue of blood. In the middle comes a double register with two scenes divided by a horizontal bar. Below lies the paralysed man, whether of Bethesda or Capernaum; above, he bears his bed away on his back at Christ's command, while the bystanders raise their hands in amazement.

Then, on the right, Christ is shown, like some victorious emperor, riding into Jerusalem triumphantly, on the donkey. The artist has been concerned to bring out as many details of the Biblical narrative as possible in the confined space. One man solemnly raises his hand as if to say, 'Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord'; others clasp branches which they have 'cut from the trees' while others again 'spread their garments in the way'. At the end an apostle holds the conqueror's garland in readiness. This type of Bethesda sarcophagus, with its crowded and confused middle section, was quite widely copied and is found as far away as Spain.

The noblest of all the sarcophagi, one that combines bold and attractive design with singular grace of craftsmanship, fortunately bears inscribed on its lid the date, 359 ad, and the name of Junius Bassus, who was prefect of Rome and received baptism on his deathbed. The front of this sarcophagus is divided by means of ornate columns into ten niches each containing a complete scene, but with never more than three figures shown, so that jostling and overcrowding are successfully avoided.

The five scenes of the upper register have a sober, elegant framework of rectangular lines, while the lower five are topped by flattish semicircles alternating with triangles, the resultant spaces being occupied by figures of lambs, delicate and charming enough but hinting at the idea of sacrifice. The profuse ornament of the carving as a whole and the gracefully posed forms suggest Hellenistic models, but the deep relief in which the figures are cut and the dignified Roman look on some of the faces point to a local artist of wide and generous sympathies. The panels are paired in a series illustrating doctrinal themes. The sacrifice of Isaac occurs at the top left while below, having lost all, Job is seated, disconsolate but faithful, on his dunghill. Next, Adam and Eve stand in shamefaced dismay; above them, the arrest of Peter suggests that the original sin and failure of mankind is countered by the atoning reconciliation to be found within the Church.

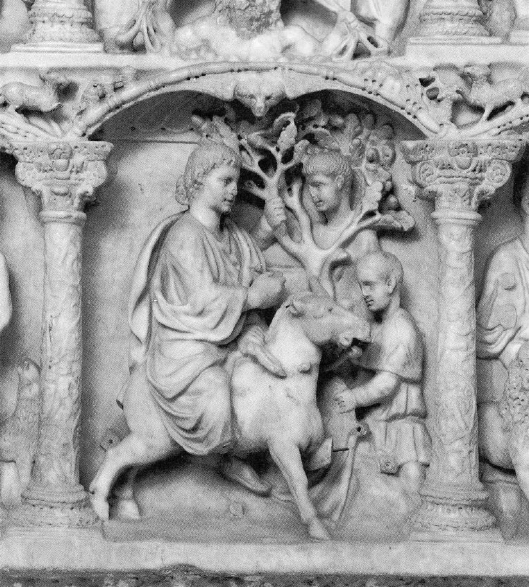

The lower panel of the central pair (fig. 41) shows Christ, graceful and half- smiling, upon the donkey that bears him to Jerusalem and to his doom; above, still the youthful counterpart of David but now calm and dignified as befits a heavenly Judge, he sits enthroned between the two princes of the apostles while the sky-god crouches beneath. The arrest of Jesus, shown once more as the prince of David's line clasping his scroll of office but with head bowed to accept the destiny of 'a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief', fittingly caps the type and example of Old Testament endurance, Daniel in the lions' den.

41. Rome, Vatican Grottoes. Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, central panel of lower row: the Triumphal Entry

Lastly, Pilate, staring irresolute into space as he prepares to wash his hands of Jesus' arrest, proclaims a worldly incapacity to perceive truth; he is contrasted with St Paul, the martyr-figure below him, who, determined but submissive in defence of the faith, inclines his head as he awaits the executioner's sword. The decoration of the ends of this sarcophagus, though conventional enough, completes the picture. The gathering of grapes, the reaping of corn and other figures which suggest the recurring seasons serve to indicate the blessedness of the eternal kingdom which the just would peacefully and thankfully enjoy.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 657;