Sarcophagi after Constantine. First part

The battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 ad may justifiably be seen as one of the turning-points of history.

Thereafter,

Constantine, the most mighty victor, resplendent with every virtue that godliness bestows, formed the Roman Empire into a single united whole. So then there was taken away from men all fear of those who formerly oppressed them; they celebrated brilliant festivals; all things were filled with light and men, formerly downcast, looked at each other with smiling countenances and beaming eyes.

In other words, the emperor Constantine brought the persecution of Christians to an end and set about using them as the cement of what he hoped would be a unified and purposeful Empire.

Christian art-forms during this period not unnaturally acquired a touch of triumph and exhilaration; buildings suddenly became large and their decoration magnificent. But the fortunes of life and death, as they affected individuals, remained uncertain, and the sarcophagi continued to proclaim that security could be found only through faith in a God whose mighty works were the guarantee of his benevolent power.

The sarcophagi of the early fourth century exhibit two principal characteristics. One group, of which the sarcophagus of the Villa Doria Pamphili may serve as an example, shows a pastoral scene set amidst all the exuberance of nature. The Good Shepherd, stocky and bearded, stands in the centre. A large tree, occupying each end, stretches out horizontal branches which, in effect, divide the entire front into three registers crammed with men, birds and beasts jostling each other in guileless companionship. The composition as a whole :

They shall come and sing in the height of Zion, and shall flow together unto the goodness of the Lord, to the corn and to the wine and to the oil and to the young of the flock and of the herd; and their soul shall be as a watered garden.

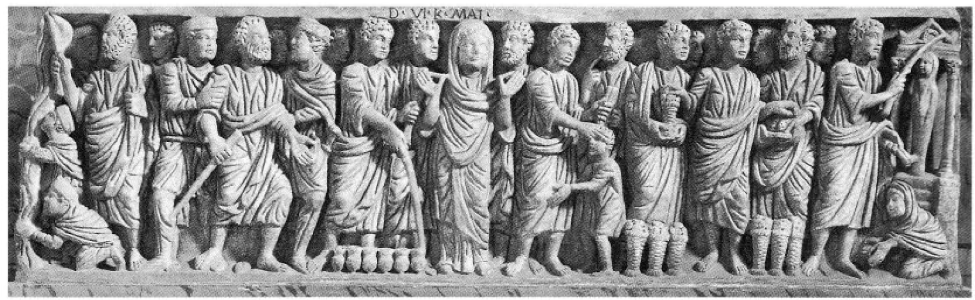

But the most typical characteristic of these sarcophagi is a tight-packed row, or double row, of figures displaying a set of Biblical scenes not always to be easily disentangled from one another. The dominant personality is Christ, displaying his acts of power and thus proving himself worthy to receive honour and glory. As in the case of the catacomb paintings, new subjects are introduced at this time but usually with a clear bearing on the central theme. Thus incidents drawn from the Old Testament, such as the sacrifice of Isaac, look ahead to the Christian dispensation, while episodes which illustrate the life of St Peter proclaim, or at least hint strongly at, the continuing miracle of Christ's power operative within the Church and spreading far and wide among the nations of the earth.

The Jairus sarcophagus in the museum at Arles (fig. 35) reveals something of this new mode of interpreting Christ's majesty. For here the middle is occupied by the figure of Christ, seated rather formally in a chair set on a plinth, as though he were another Diocletian or Constantine. Meanwhile the apostles offer their homage in the conventional manner, veiling their hands and inclining their bodies. During this period, however, such a display of obsequious reverence was rare: more typical are the Vatican sarcophagi 191 and 161, which show a similar frieze effect but in two distinct forms. Number 191 represents the group of Abraham-Christ sarcophagi in which Old Testament scenes are eagerly introduced as a commentary on Christ's achievement.

35. Arles, Musee Lapidaire d'Art Chretien. Sarcophagus: Christ seated among the Apostles and the raising of Jairus's daughter

The usual practice is to show, at the left corner of the tomb's face, Abraham preparing to slay his son Isaac—an event which was held to forecast the Crucifixion. As a symmetrical counterpart of this incident, Christ arouses Lazarus from the tomb and the churchman is thereby reminded that Christ by his death awakes mankind from death. The obvious symbol of this conquest of mortality is the life-conferring Eucharist indicated, in the middle of the frieze, by Christ multiplying the loaves of bread for those who otherwise would have starved to death.

On this particular sarcophagus the Lazarus scene is not shown in accordance with the usual convention of the mummified figure standing at the entrance of his tomb. For here Christ, attended by two apostles, stretches out his magician's wand to touch the head of a dead man—whether Lazarus or another—lying at his feet, while nearby the corpse's counterpart stands, diminutive but very much alive. What the artist has done is to compress not only the spatial extent of the picture but also its time-sequence: the 'before and after' of Christ's action are shown as simultaneous parts of one miracle of deliverance.

The standard themes found in this type of frieze sarcophagus were often filled in, more or less according to taste, with shorthand versions of Gospel events or their prefigurations in the Old Testament. Vatican sarcophagus 191 illustrates Christ healing the man born blind, the paralytic and the woman with the issue of blood. Accompanying these scenes is another, marking the cause of the distresses which require Christ's intervention, namely Adam and Eve standing coyly beside the Tree of Knowledge and clasping their figleaves to their bodies. One end of the sarcophagus is decorated with Moses striking the rock, the other with Daniel and with the three men in the fiery furnace. Thus the artist, ranging his figures in a stiff, rather monotonous manner, has found himself able to include a great deal that, to the understanding eye, would make for edification and comfort.

Sarcophagus 161 belongs to the other contemporary group, which omits Old Testament subjects and chooses instead events from the life of St Peter. The three most commonly shown are the denial of Christ, who gazes reproachfully at Peter as the cock crows, the arrest, when two soldiers in flat helmets and military boots grasp the Apostle from either side, and the scene where Peter is likened to Moses, as the inspired wonder-worker capable of causing water to flow even from the stony rock (fig. 36).

36. Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 161: miraculous events. Peter drawing water from the rock balances the raising of Lazarus

This last illustration was deemed to be of especial significance and it therefore occupies one corner of this and other sarcophagi, balancing the miracle of Lazarus at the opposite end. In one of the many apocryphal stories which circulated in Rome concerning Peter, it was recorded that the stream of water from the rock so astonished the Roman soldiers who benefited from it that they embraced Christianity.

But the point stressed on the sarcophagi is not conversion but the flow of the water of life dispensed by the chief of the apostles. In the third century the idea that the salvation of God may be readily symbolized by the refreshing power of water receives artistic expression in pictures of the Baptism of Christ, Moses striking the rock or the Samaritan woman at the well. Thereafter St Cyprian's view prevailed, that the Church alone has power to dispense this saving grace. With the increasingly firm belief in the authority of Peter and his successors, this gift is displayed as mediated by Peter representing the Church.

The two corners of sarcophagus 161, and others in the same group, are thus closely connected as depicting two parts of one process. Peter, as he causes the saving water to flow, indicates the starting-point of a Christian life—reception through baptism within the bosom of the Church—while Christ, raising Lazarus from the tomb, shows concretely that the end of a Christian's course on earth is advancement to eternal life.

Peter and Christ complement one another as Pupil to Master, Church to Eternity, Prophecy to Fulfilment. Appropriately enough on sarcophagi of this type, the central position is taken by an Orans, the faithful soul who is the subject of this stupendous process, and the water pots of Cana no less than the baskets containing bread enough to feed five thousand hint at the sacramental means whereby the life of the faithful is maintained within this divine economy of redemption.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 686;