Stone Carving. The Sarcophagi

As with painting, so with sculpture. The Christian church unselfconsciously adopted the classical fashion of carving stone surfaces with figures in relief. The noblest and earliest example of this technique in Rome is the Ara Pacis Augustae, a monument dedicated by the Senate, about ю вс, to commemorate the safe return of the emperor Augustus from military operations in Gaul and Spain. The building consists of an altar enclosed within walls that are decorated on two sides with a procession of men advancing in pairs.

The whole composition, sometimes described as a Romanized version of the Parthenon frieze, breathes a spirit of controlled grandeur, while the variety of the figures and the sense of perspective gained by alternating high with low relief bestow a liveliness not always found in the columns and triumphal arches set up a little later by the emperors. The east and west sides of the Ara Pacis show figures, not in procession but in static groups, celebrating the rites of sacrifice or enacting scenes drawn from classical myth; the frieze below luxuriates with foliage.

What is here demonstrated is the complexity of Roman artistic taste. A liking for clear, realistic portraiture joins with religious or allegorical scenes as if to show that human life, however down-to-earth, is touched with mystery and aspiration, just as the frieze pattern of leaves and tendrils bears witness to keen, Wordsworthian delight in the varied charm of Nature's works. Not all Roman carving in relief matches the quality of the Ara Pacis; it can easily become lumpy and overcrowded or degenerate into the lifeless repetition of standard themes, as may be observed in certain of the sarcophagi.

Sarcophagi are large but moveable coffins originally, it would seem, developed from the sculptured tombs of Asia Minor. The Etruscans made use of stone sarcophagi with figured lids showing people recumbent at a banqueting-couch and in Rome, as the practice of cremation gradually declined, sarcophagi made to contain the bodies of distinguished personages came into fashion. Many of these coffins were produced in Asia Minor for export. Some, particularly those made of marble from Proconnesus, are decorated on all four sides with wreaths of flowers or leaves and bunches of grapes.

The stone sarcophagi, by contrast, usually show human figures, carved in high relief, standing or sitting within niches marked off, one from the other, by the roofs and columns of Greek architecture. On occasion Apollo and the Muses are introduced as a theme suggesting the harmonies of heaven or, with no less acceptance, the Labours of Hercules, as a reminder that perseverance in arduous and honourable tasks brings its eventual reward. Another type of sarcophagus, perhaps a more purely Roman product, was carved on three sides only, the back being left plain in order to fit against a wall: the ends, whether squared or rounded, often had a mask or lion's head as decoration.

The front of the sarcophagus was treated in various ways, and three principal types may be distinguished. The first consisted of panels, plain or fluted, with a portrait bust of the deceased in the centre. Another type was characterized by heavy, stiffly carved garlands of fruit and flowers, upheld by cupids, nymphs or Victories. The garlands resembled those presented to the dead at the time of burial or on their anniversaries, while the cupids and other allegorical figures conferred a vague aura of other-worldliness, touched here and there with terror when ghastly masks stood out, in harsh contrast, against the rich abundance of natural life.

On the third type of sarcophagus, however, there could be clearer and more definite representations, with human figures standing immobile like statues on the west front of a Gothic cathedral or, more often, jostling together in a melee which only great artistic skill could preserve from confusion. These scenes sometimes displayed the works of husbandry appropriate to the various seasons. More often, however, well-known incidents from ancient story were set forth—Bacchus, perhaps, revelling in triumph over evil, or Dionysus, in all the charm of youthful beauty, rescuing Ariadne, asleep on the Naxian shore, from the envious grasp of Death. Such was the heritage of forms and ideas readily taken over -by the Church when the first Christian sarcophagi came to be made in the late third century ad—a period in which the wealthier Christians found themselves able to emulate pagan neighbours in the splendour of their funeral arrangements.

The best and most frequent examples of Christian sarcophagi are, naturally enough, to be found in Rome; many of them are now gathered in the great collections of the Vatican and the Museo Nazionale. But Spain and North Africa have supplied quite a number, while the agreeable and civilized Province of Southern Gaul (later Provence) has yielded sarcophagi of high quality that deserve to be seen as products of a distinctive local school, with Arles as its centre.

Most of the early sarcophagi were made of marble, commonly white Carrara, though coarse-grained marbles from the Ionian Islands and veined marble from Asia Minor were regularly imported. Porphyry, by reason of its rarity and the magnificence of its purple colour, seems to have been reserved for members of the imperial house. The sculptors preferred to work on a single block but might be obliged, if their patrons tightened the purse-strings, to piece together coffins from several chunks of marble, not always suitably matched, or to carve in one of the softer, and cheaper, limestones.

The sculptor worked with two tools, the chisel and the drill, this last being used for boring holes to indicate eyes or other features and for channelling out the lines of drapery. One such Christian craftsman is known by name, Eutropus, and his grave-slab, discovered in the Cemetery of SS. Marcellinus and Peter in Rome, has on it, beneath the elegant lettering of the inscription, a rough engraving of Eutropus at work. He is seated in a chair opposite a raised sarcophagus on which wavy lines and lions' heads have already been carved, and, assisted by an apprentice, he operates the drill by means of a cord; near his feet lie chisel and mallet.

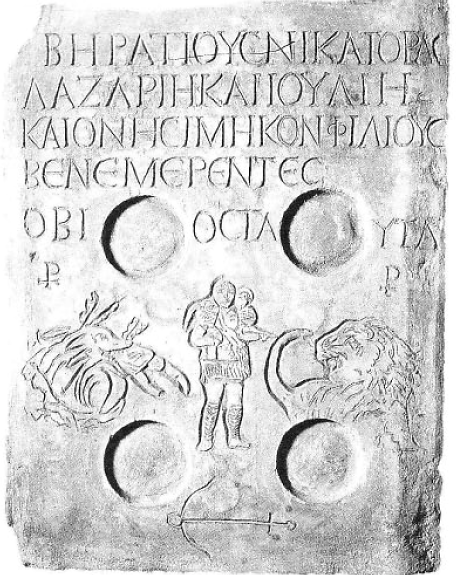

Occasionally the marble was tinted with yellow, red, gold, or blue, and became a 'polychrome'. The colours could be lavishly applied, in the way the Etruscans had liked to treat marble, but more often the figures were delicately touched so as to soften the portraiture and give it a supernatural reference. By contrast with such graceful artistry some of the carving was extremely crude. One example of this rough but undeniably sincere workmanship is the inscription of a certain Beratius, now in the Vatican Museum (fig. 30).

30. Rome, Vatican Museum: the inscription of Beratius

This, a grave-slab rather than a sarcophagus proper, exhibits three figures: on the left a ravenous monster of indeterminate type is swallowing a man; on the right a roaring lion raises a paw to strike; in the centre stands the Good Shepherd. The drawing may be childishly incompetent, but fear of death could hardly be more vividly displayed than by the man, nor firmer hope represented than bv the shepherd with the lamb straddled over his shoulders and the symbolic anchor at his feet.

While the Christian sarcophagi cannot be precisely dated, the general course of their development is reasonably clear. The turbulent conditions experienced in the early part of the third century, when emperor succeeded emperor with bewildering rapidity, gave a certain topical appropriateness to the vast battle sarcophagi with which victorious generals were honoured. But expressions of pride and triumph gave place to the agonized grimaces of suffering just as, on the companion-pieces which illustrated lionhunts, courage and vigour came to be less emphasized than the ferocious torments which beset mankind.

The Christian version of this theme, following the pattern of the Beratius inscription, is illustrated by a large tub-shaped sarcophagus found at Rome but now preserved in the Louvre (Number 2982). On this coffin a juvenile Good Shepherd is shown, standing between two trees. He bears an enormous ram on his back, while a smaller sheep at his feet looks confidently upward. On either side, near the two ends of the sarcophagus, appears a very large lion’s head, with elaborate mane and mouth savagely opened to gobble up those who have no protector.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 531;