Sarcophagi after Constantine. Second part

Sarcophagus 161 is one of those richer in symbolic content than in artistic achievement. Participants in the action, together with the onlookers, are lined up in two rigid rows, facing more or less straight ahead in stiff formality. Other examples of the same period are less crowded and rather more flexible in the arrangement of the figures. Thus the Monograms Sarcophagus, found during excavation under the Vatican, displays vigour of movement as well as a somewhat more adventurous rendering of the scenes. At the left corner, the soldier drinking from the stream of water is no diminutive puppet but stands, stern and strong-featured, as tall as St Peter.

The Apostle, in his turn, performs two functions. With his right hand he clasps the wonder-working rod, but his face is sharply turned away from the thirsty soldiers to confront the youthful Christ, shown with long, curly hair, right hand raised in blessing, or reproof, and left hand clutching a scroll marked with the sign of victory. Meanwhile the cock, looking more like a fanciful bird from some medieval bestiary, crows vociferously. The deep-channelled lines which mark the folds of the garments run in contrasting directions and the whole scene conveys liveliness and spiritual tension.

The crowded appearance of the frieze sarcophagi is avoided in the variety which alternates carved scenes at the ends and in the centre with two panels of wavy 'strigillations' cut in the stone. There is less condensed instruction to be had, but the eye is rested by the curving lines and can concentrate more readily on the subjects illustrated. These are usually of the conventional type. One sarcophagus from the Catacomb of Praetextatus shows an Orans, in the centre, being escorted to Paradise by two venerable companions who are no doubt the apostles Peter and Paul, while at each end an identical Good Shepherd, with a bulky ram on his back, turns a benevolent gaze in the direction of the Orans.

Occasionally a more surprising combination of themes is offered, as on a sarcophagus from the monastery of St Catherine at Rome. Here the central scene displays Christ as teacher, between two disciples, while at each end a winged, naked male figure clasps a half-clothed female form. The classical emblems of Amor, the divine Love, embracing Psyche, the individual human soul, here replace the Biblical sign of the Good Shepherd.

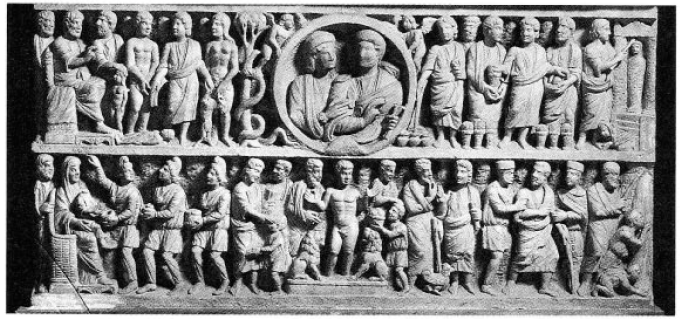

Another means whereby some feeling of repose may be obtained amid the confused activity of a frieze is when a circular 'tondo', containing a portrait of the deceased, interrupts the narrative. From the viewpoint of artistry this device of the tondo becomes particularly effective when, in the full development of style during the reign of Constantine, the lessons of Christian history are deployed in a double row, separated merely by a straight horizontal line. An important example is supplied by the Trinity Sarcophagus (Vatican 104) where the workmanship seems, though more elegant, akin to that found on Constantine's great triumphal arch. On this sarcophagus (fig. 37) the story' of Fall and Redemption is given a pleasantly personal twist.

37. Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 104: the Trinity Sarcophagus

The upper register begins with the creation of Eve, who receives a blessing from the three Persons of the Godhead, shown as dignified, bearded men, while Adam lies supine on the ground. Closely attached to this scene is another, in which God, appearing this time as a young man with curly hair, stands between the naked Adam and Eve while the Serpent, unabashed, coils its way up the Tree of Knowledge. As if to show that there are grounds for hope, a lamb stands on its hind legs in front of Eve, reaching up towards her. The tondo follows, upheld by two little angels. It contains a realistic portrait of husband and wife, their faith indicated by the scroll of Christian learning which the man clasps in his left hand. The other half of the top register contains the two sacramental scenes of the water at Cana being turned into wine and the Multiplication of the Loaves.

Finally comes the conventional Lazarus scene which includes Mary, the sister of Lazarus, or perhaps the woman with the issue of blood, crouching at the feet of Christ. Immediately below the portraits of the deceased man and wife, and thus in the centre of the composition, appears the sturdy figure of Daniel standing on a plinth which represents the lions' den. The two lions, one at each side, have the air of heraldic animals rather than of ravenous beasts and over their head Habakkuk is allowed quietly to pass the basket of loaves which sustained Daniel in prison. This whole scene, set at the focal point of a funeral monument, suggests the safe emergence of human souls from the midst of trials and danger.

The left side of the lower register is taken up almost entirely with an extended illustration of the visit of the Magi. Joseph sfands in amazement behind the throne on which the Virgin sits as the Three Wise Men, wearing their pointed Phrygian caps, approach expectantly with their gifts for the Christ child. This intimation of the Redeemer's advent is designed to balance precisely the Creation and the Fall, shown by the figures above; thus there is space only for a very compressed version of the healing of the blind man before Daniel appears. Then, on the other side, the mission of the Church is suggested by the three customary incidents from the life of St Peter—the denial, with Peter clutching his beard in dismay, the arrest, and the water drawn from the barren rock to help the thirst)' soldiers. Recessed behind the protagonists, a number of heads imply that the drama is of universal importance.

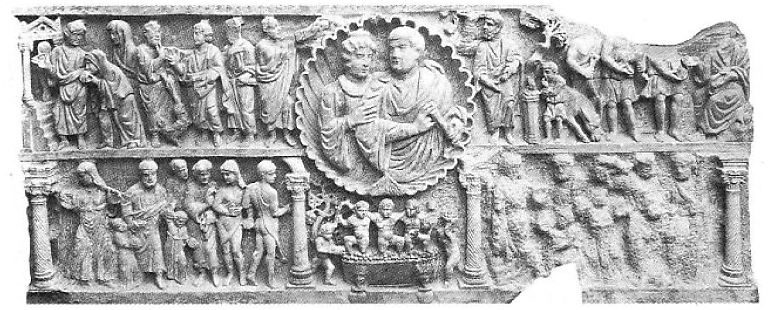

As the fourth century advanced, the sculptors came to realize that a jumbled frieze, however rich in symbolic value, might become obscure and tedious to look at. They therefore emphasized the central tondo, now often enriched with channelled decoration, to such an extent that the busts of the departed, much larger in scale than the other figures, dominate the whole. Probably the noblest example of this style and period is the Two Brothers sarcophagus in the Vatican Collection (fig. 38). Here the central medallion, in classic scallop-shell form, contains the busts not of husband and wife but of two grave and bearded men so alike that they may well have been twin brothers.

38. Rome, Vatican Museum. Sarcophagus 183B: the Two Brothers

The figures which compose the various scenes are no longer sketched in low relief; they stand out to a depth of about 15 centimetres, like so many statuettes, delicately modelled, with deep-set eyes directed on far, eternal realities. There is a certain novelty in both choice and treatment of the subjects illustrated. At the left corner of the upper register the gabled columns of Lazarus' tomb are shown in conventional fashion, but no corpse fast tied in burial bands can be seen at the open door. Instead, Mary, the sister of Lazarus, bows forward to kiss the hand of Christ. This touch of indirect suggestion and human pathos is matched by the appearance of Christ himself, a graceful youth who expresses the keenest sympathy as he inclines his head gently towards the woman whose grief has been turned to sudden joy.

This natural mode of portraiture and concern for historical event is borne out at the other end of the frieze, where there occurs a rather elaborate representation of Pilate preparing to w-ash his hands in token that he is 'innocent of the blood of this just person'. This scene can hardly be regarded as a compact symbol; rather it bears witness to a vivid interest in the details of the Passion story and those who participated in it. Pilate is shown not as a stylized figure but as an individual Roman, authoritative yet gripped by doubt and apprehension. The space immediately below the scallop-shell medallion once more displays the confident figure of Daniel between his upward-gazing lions.

But beside Daniel, and still beneath the medallion, another subject is illustrated: an elderly scholar sits contemplating the tablets on which his philosophy is inscribed while two soldiers stand nearby, one clutching at the precious tablets, the other spying through a tree. This scene, which might be the equivalent of Peter's arrest, is of artistic importance by reason of the two trees, one stunted, one with clumps of deeply-drilled foliage, which frame it. For the trees serve to check the monotony of figures in sequence, and thus lead up to the system of dividing a frieze into panels by means of columns.

An early essay in this style (about 340 ad) is provided by the Sarcophagus of Lot, recently discovered near the church of S. Sebastiano in Rome (fig. 39). The workmanship of this sarcophagus rivals the finest pagan examples; indeed the rhythmical symmetry of the well-spaced figures and their imaginative poses have about them an air of Renaissance culture. This impression is confirmed by the traces of colour still evident and by the ready alliance of pagan with Christian themes. The upper row of subjects, flanking the husband and wife in their scallop-shell medallion, closely resembles the arrangement of the Two Brothers sarcophagus, but the lower register is entirely different.

39. Rome, S. Sebastiano: the Sarcophagus of Lot

Two robust columns, with capitals and the suggestion of an arch springing from them, enclose the dramatic spectacle of Lot's flight from Sodom. The other side is similar in pattern though here, for whatever reason, the figures have been left incomplete. But immediately below the medallion with its portraits of the departed, five naked little boys trample out the vineyard grapes in a Bacchic ecstasy of abundant vitality; the lid of the sarcophagus with its cherubs and hunting-scenes repeats the theme of life and vigour.

The use of columns, suggested by the Sarcophagus of Lot, led to the adoption in the Roman workshops of a dignified, formal style which, in the middle of the fourth century, transformed the muddled lively frieze into a range of separated scenes, each within its own frame. Yet the message of the sarcophagi retains its unified character by reason of the closest connection between one subject and another, nowhere more clearly shown than on the various 'Passion- sarcophagi' which compose, at this period, a clearly- marked group. The interest has shifted momentarily from Christ as wonder-worker to Christ victorious through suffering. The suffering is real enough, but it is understood in terms of triumph rather than pathos, of hope for all rather than despair.

The sarcophagi are, in fact, an artistic expression of doctrines which were being pronounced at the time by such Fathers of the Church as Athanasius:

For the Word, knowing that the corruption of men could not be undone unless there was a death, and it was not possible for the Word to die, being immortal and the Son of the Father; for this reason he takes to himself a body that can die, so that this body, sharing in the Word who is above all, may become liable to death on behalf of all, and on account of the indwelling Word may remain immortal, and in future the corruption may cease in all by the grace of the resurrection.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 680;