Characteristics of Amphibians and Reptiles. The second part

Another salamander family, the Salamandridae or newts, undergo normal metamorphosis. After spending a period as terrestrial efts, they return to the water to breed, undergoing a second major change in form (although larval features are not regained). During all life stages, newts are protected by potent skin toxins, which make them unpalatable to all but a few potential predators. Newts, which occur as close as British Columbia, often have elaborate underwater courtship displays. Males deposit packages of sperm (spermatophores) on the substrate and entice females to pick them up with the lips of their cloaca. Fertilization is thus internal, as it is in most salamanders, although copulation is not involved.

The most speciose family of salamanders is the Plethodontidae. These are remarkable in that they lack lungs and exchange almost all of their respiratory gases through the skin. The tongue skeleton, which in most salamanders helps to force air back into the lungs, no longer has a dual function and is devoted entirely to assisting in prey capture. In some plethodontids, the tongue may be rapidly extended to distances almost as great as the length of the body, allowing the salamanders to capture insect prey at a considerable range. Plethodontids are also unusual in that most species do not exhibit a free larval stage. The eggs are laid in terrestrial nests and the embryos undergo direct development, hatching as miniature versions of the adults.

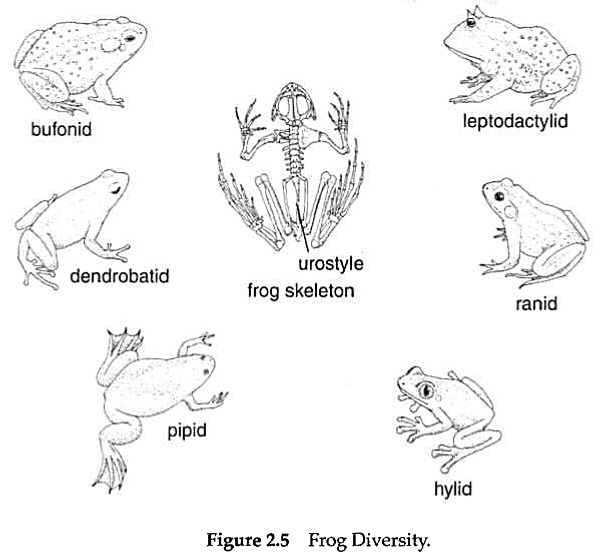

The frogs and toads (Fig. 2.5) constitute by far the largest group of amphibians. The more than 4,300 species are divided into about twenty-four families. Frogs and toads occur throughout the world, except for Antarctica and many remote oceanic islands. Anurans are immediately recognizable by: their short and compact bodies; elongate hind limbs; relatively short fore limbs; lack of tail; prominent eyes; lightly built skull; urostyle (fused and compacted caudal vertebrae); absence of free ribs; prominent tympanum (ear drum); external fertilization preceded by amplexus (male grasps female from dorsal surface); voice; and morphologically distinct tadpole larvae. Anurans are generally small, with some Eleutherodactylus being less than 12 mm in body length. There are, however, some relative giants such as Conraua goliath, a ranid frog from Africa, which attains a body length of 350 mm and a weight of three kilograms or more.

Unlike some salamanders, all anurans must undergo metamorphosis before they are able to breed. Many, however, undergo some or all of their premetamorphic development in the egg, often away from the water in specially constructed nests, but sometimes in the reproductive tract of the female. In some groups, the eggs or larvae are brooded in special pouches on the dorsal or lateral surfaces of the body, in the vocal sacs of males, or even in the stomach, as in the gastric brooding frog, Rheobatrachus silus of Australia. Typical free- living tadpoles are radically different in appearance from adults, much more so than are the larvae of salamanders when compared to their adults. Many organ systems are not expressed for much of the larval period, and metamorphosis is rapid and drastic. The diet, habitat and general ecology of the larvae are all forsaken for those typical of the adults.

One of the most notable traits of frogs in general is their ability to vocalize. The Amphibia is the first of the vertebrate groups to have a larynx (voice box). This is formed from the modified anterior end of the trachea (windpipe). With its associated cartilages and vocal cords, the larynx enables sounds to be produced. Tightening or relaxing of the vocal cords causes variations in pitch. Male frogs usually possess vocal sacs which act as resonators to help broad- cast species-specific advertisement calls to females. Vocalization is chiefly associated with mating, and the calls of frogs are as characteristic as those of birds. Most frogs do not have elaborate court- ship rituals like those of many salamanders. Rather, males grasp females in amplexus, and gametes of both sexes are shed into the water. Amplexus may persist for long periods of time. External fertilization is the rule in all frogs except a few representatives of the large families Bufonidae and Leptodactylidae, and in Ascaphus truei, the tailed frog (which may enter Alberta in the region of Waterton Lakes National Park).

Some frogs have toxins similar to those of salamanders. These include the tropical American dendrobatids, or arrow-poison frogs, as well as the true toads (Family Bufonidae), which are represented by three species in Alberta. In the genus Bufo, the poison is largely concentrated in large parotoid glands behind the eyes and is often more noxious than deadly. The secretion of certain arrow-poison frogs, however, is the most powerful animal-derived toxin known. The skin of a single arrow-poison frog may contain enough toxin to kill 10-20,000 mice. Many frogs, nonetheless, rely on their agility as a means of escape. Most features of frog anatomy are in some way related to modifications of the body for jumping or swimming.

The hind limbs are powerfully built and provide the thrust for both of these activities. The forelimbs and shoulder girdles of most terrestrial frogs are likewise modified as shock absorbers that receive the weight of the animal upon landing. Some frogs are capable of jumps exceeding five metres. Certain frog groups are characterized as being permanently aquatic. These include the pipids, of which Xenopus, a common laboratory animal, is an example. None of the Alberta species is exclusively aquatic, although Rana luteiventris spends much of its time submerged. Many more frogs have abandoned the water for the trees and are modified for an arboreal existence. Hylid frogs, in particular, have adhesive toe pads which help them cling to vegetation. In spite of the difficulties of obtaining water, frogs have also invaded desert regions, where burrowing and nocturnality protect them from excessive dehydration. In some frogs, water loss is also slowed by keratinization of the skin, or the secretion of a protective waxy layer over the exposed surfaces of the body.

Frogs are typically insectivores, although other prey may be taken. Most frogs obtain their prey by flipping out their tongue, which attaches at the front of the mouth. Tadpoles feed primarily on vegetation or detritus and may themselves be food for aquatic insects, fish and other tadpoles.

Despite the many differences between caecilians, salamanders and frogs, all share certain problems in dealing with their environments. Amphibian skin is typically highly permeable, and amphibians are prone to desiccation if exposed to a drying environment. Ultimately, most amphibians rely on a source of water for reproduction and larval existence. Such constraints have circumscribed the habitats and ecological niches available to amphibians. The strategies employed by amphibians to deal with the problems posed by the environment will form the basis for portions of the second part of this book.

Reptiles, which arose from an amphibian stock (Fig. 2.1), have escaped from many of the constraints acting upon living lissamphibians by way of two major innovations: a desiccation- resistant keratinized skin, and a shelled egg that permits direct development on land. Reptiles are therefore much more terrestrial than amphibians, and their distribution is not so closely related to the availability of free water.

Reptiles first appeared in the Carboniferous Period (about 330 million years ago) and radiated in the Permian period and through - out the Mesozoic Era. The latter is commonly known as the "Age of Reptiles" and is testimony to their apparent dominance in terrestrial situations during this time. Most conspicuous were the various groups collectively known as the dinosaurs. Until their sudden demise at the end of the Cretaceous Period (about 65 million years ago), the dinosaurs were the major large herbivores and carnivores throughout most of the world. The dinosaurs were representatives of a large group of reptiles known as the archosauromorphs. Other members of this lineage include the crocodylians, which still survive, and the flying pterosaurs. Birds too are archosauromorphs and, in fact, are the living legacy of the dinosaurs, current orthodoxy suggesting that they are their direct descendants.

The archosauromorphs are one major branch of a group of reptiles known as diapsids (= two arches) because of the configuration of bones on the side of the skull, behind the eye. The other major diapsid lineage is the Lepidosauromorpha. This group contains less spectacular animals, but includes the most successful of the living reptiles, the squamates (lizards and snakes), and their close relatives, the tuataras. Mesozoic reptiles also invaded the marine environment, a feat never achieved by the amphibians. The most well-known of these were the plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, which have no living relatives.

Another reptile group with some marine forms are the turtles. These animals established their particular body plan during the "Age of Reptiles" and have persisted relatively unchanged since that time. Synapsid reptiles, on the other hand, were also established early, but their history led them to one of the major transitions among tetrapods, resulting in the origin of mammals in the Triassic. Not surprisingly the synapsids are also known as the mammal-like reptiles.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 768;