Characteristics of Amphibians and Reptiles. Fourth part

All turtles lay eggs which, even in sea turtles, are buried on land. In some turtles, the choice of egg-laying site is especially important as it may influence the sex ratio of the offspring in the clutch. In these turtles, sex determination is temperature-dependent rather than genetically programmed. The depth of individual eggs within the nest exposes them to different temperatures along a temperature gradient. Eggs deeper in the nest, where temperatures are cooler, will form males, while eggs incubated at warmer temperatures, nearer the surface, yield females. The temperature at which this transition occurs may vary with latitude, both within and between species. If they survive to maturity, individuals of most turtle species may live to relatively old ages. In at least some species of tortoises (Family Testudinidae), longevity may exceed one hundred years.

One of the largest families of turtles is the fresh-water Emydidae. This is primarily a northern group of turtles with many representatives in North America. Alberta's only confirmed chelonian, Chrysemys picta, is a representative of this group and is rather typical in its general features. This family and all of the northern turtle families are characterized by their ability to bend the neck in a vertically directed S-shaped curve. Many can draw the entire head and neck into the protective shell.

This group of turtles, the cryptodires, has a southern hemisphere counterpart, the pleurodires, which bend the neck in a horizontally oriented curve and cannot hide the head under the carapace. The carapace itself influences all aspects of turtle biology. It is formed by bony plates derived from the skin that fuse with one another and with the ribs and vertebrae. Turtles also possess a ventral shield, the plastron, which may be attached to the carapace by a bony bridge between the fore and hind limbs. In some forms, such as box turtles, the plastron may be hinged to allow it to be closed against the carapace when the head, limbs and tail are withdrawn. The shell may be reduced in some species, such

as Chelydra serpentina, the snapping turtle, which has a reduced plastron, sea turtles (Families Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidae), which have reduced carapaces, and soft-shelled turtles (Family Trionychidae), which have both components reduced and exhibit a rather fleshy shell.

Despite their relatively small number of species, turtles play an important economic role in many human societies. The outer covering of the carapace of sea turtles, "tortoise shell," is valued for its decorative properties. Sea turtles are also hunted for their meat and eggs. Snapping turtles and many other species are also sought after for their flesh. Turtles are popular in the pet trade. In the case of some species, these various human pressures on populations have resulted in a drastic decline in numbers, and even extinction.

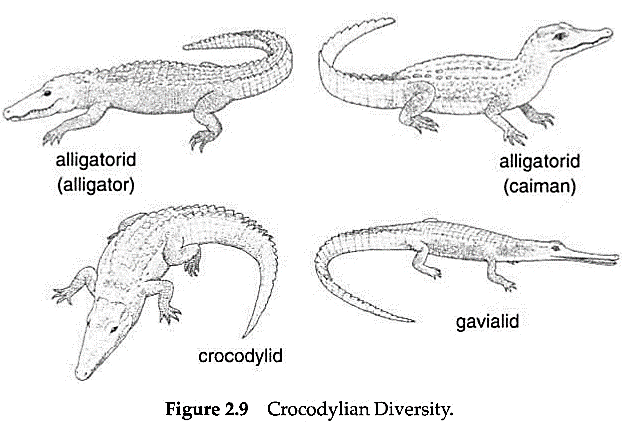

Crocodylians (Fig. 2.9) are a group of twenty-three species of archosauromorph reptiles that today occur mostly in the tropics and subtropics. They are quadrupedal and generally largely aquatic. Some species occur in salt water and may travel great distances at sea. Crocodylians, which include alligators, caimans and gavials, as well as crocodiles proper, are characterized by a diapsid skull; elongate, well-toothed jaws; a secondary palate; lack of clavicles (collar bones); abdominal ribs (gastralia); a specialized ankle joint; osteoderms (bony plates) in the skin; a four-chambered heart; presence of an unpaired penis; and a laterally compressed tail, often with a single or paired dorsal ridge. All crocodylians are large, with several species exceeding six metres in total length.

Only two crocodylians are native to North America. Crocodylus acutus is found in southern Florida and Alligator mississippiensis is widespread in the southeastern United States. Like turtles, crocodylians are hunted, primarily for their skins which are used in the manufacture of leather goods. This activity was responsible for a great decline in alligator populations earlier in the century, but with government protection alligators have returned to many areas of their former range. In many areas of the world, crocodylians are farmed for their hides and meat. Crocodylians may also interact with humans in another way. Because of their large size, they may be dangerous, especially during the period of reproduction and brooding, and have been responsible for human deaths.

Crocodylians rely exclusively on animal prey. Smaller individuals may take insects and small vertebrates while larger animals eat fish, reptiles and mammals. Crocodiles have a complex social behaviour, and the adults provide parental care to the young. As in turtles, nest sites are chosen carefully as sex is determined by temperature. In the American alligator, intermediate temperatures produce males, whereas low or very high temperatures produce females.

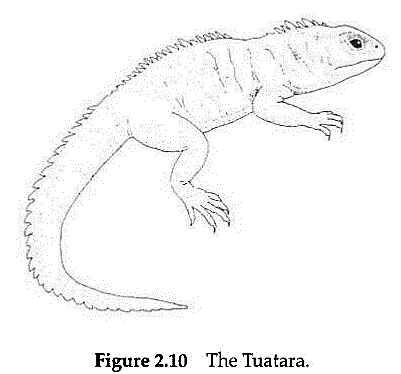

The tuatara (Fig. 2.10), Sphenodon punctatus, is placed in a group of its own, the Sphenodontia. A second species has recently been recognized on the basis of genetic differentiation. Tuataras are the sole survivors of a major radiation of lepidosauromorph reptiles. The tuatara, which is lizard-like in appearance, occurs only on about thirty small islands off the coasts of the main islands of New Zealand. It may be distinguished from its nearest living relatives, the squamates (lizards and snakes) by its possession of an unmodified diapsid skull; overlapping processes on the ribs (uncinate processes); gastralia (abdominal "ribs"); absence of a tympanum; and absence of a copulatory organ in males. Tuataras reach sixty centimetres in total length and over one kilogram in weight. Males are larger than females.

Sphenodon is extremely long-lived, reaching confirmed ages in excess of sixty years. Sexual maturity is not attained until an age of approximately twenty. This longevity is related to the low temperatures in the animal's environment (for reptiles, which are ectothermic, age is perhaps most meaningfully measured in terms of metabolic rate rather than absolute time). Tuataras are generally active at night and frequently tolerate temperatures below 10°C. By day, they occupy burrows which may be those of seabirds (with which they may cohabit) or of their own construction. Although they are probably primarily insectivorous, tuataras may also eat lizards and the seabirds that share their daytime retreats.

Fertilization by way of copulation occurs about nine months before females lay eggs in burrows excavated for that purpose. Incubation lasts about twelve to fifteen months, the longest period known for any living reptile. The eggs and juveniles are especially sensitive to predation, and the introduction of non-native mammals, especially rats, has wreaked havoc on some tuatara populations. Before the advent of man (and with him, other mammals), Sphenodon was widespread on the larger islands of New Zealand.

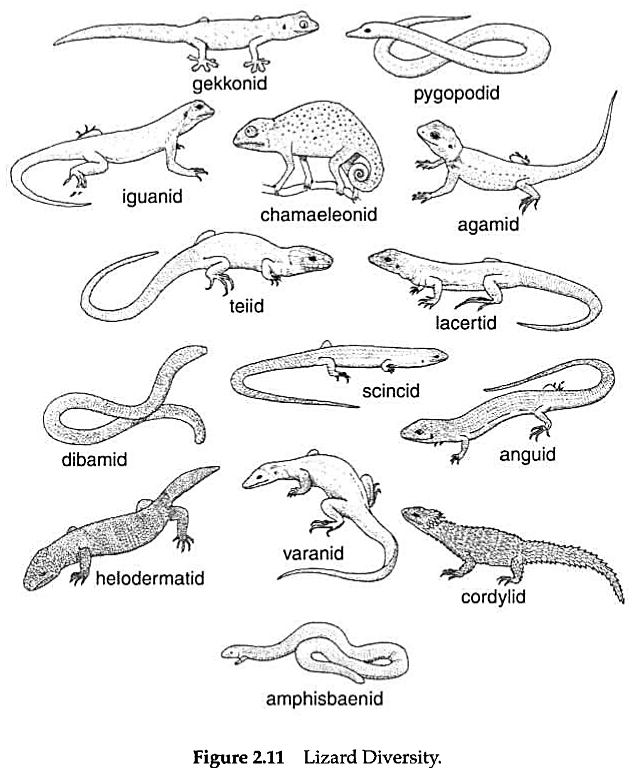

The vast majority of living reptiles belong to the Squamata. The two groups included in this order are the lizards and snakes. Snakes, however, arose from within lizards. Lizards can, therefore, only be defined as squamates that lack the special features of snakes. Squamates are characterized by a streptostylic (moveable) quadrate bone in the skull; a reduction in the original diapsid skull arches; paired copulatory hemipenes in males; and absence of gastralia. In addition, lizards possess the following features that have been evolutionarily lost in snakes: specialized wrist and ankle joints; gracile limbs; and a "heel" formed by the hooked metatarsal bone of the fifth digit.

There is a great deal of variation among the more than 4,000 species of lizards (Fig. 2.11). They range throughout the world except for very high latitudes. In size, they range from geckos (Family Gekkonidae) less than forty millimetres in total length to Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis, Family Varanidae) occasionally reaching three metres in length. Fossil varanids were even larger, and the closely related aquatic mosasaurs were the largest liz- ards ever to have existed, reaching lengths of more than ten metres.

Most lizards are insectivorous, but some larger species are carnivorous and others are largely or entirely herbivorous. The beaded lizards (Family Helodermatidae) employ venom in subduing prey and are the only lizards to do so. For most lizards, prey capture involves the use of the jaws, but in some forms, exemplified by chamaeleons (Family Chamaeleonidae), the tongue is used as a prehensile tool to capture small prey items. Like some plethodontid salamanders, chamaeleons are able to very rapidly project the tongue to a great distance. The mechanism used by these animals, however, is rather different from that of the lungless salamanders.

Chamaeleons also differ in their style of locomotion from most other lizards. Typical lizards (such as those of the families Iguanidae, Lacertidae, Agamidae and Teiidae) have a sprawling posture and move by a combination of lateral undulations of the body and powerful strokes of the limbs. Chamaeleons, on the other hand, have compressed bodies, erect posture and move slowly and deliberately with little involvement of body motions. Climbing is common in lizards but has reached its extreme in the family Gekkonidae.

Many geckos possess a complex adhesive mechanism that allows them to adhere to smooth surfaces and even to ascend vertical faces and hang upside down. Representatives of many other lizard families, on the other hand, have partially or wholly forsaken limbs, usually in association with a burrowing lifestyle. Such forms move in a serpentine fashion, sending waves down the length of the body and pushing against the substrate with their ventral and lateral scales. Examples of these types can be found in the families Pygopodidae, Dibamidae, Anniellidae, Scincidae, Gymnophthalmidae, Anguidae and the gerrhosaurs among the Cordylidae.

Another group, the amphisbaenians, are also chiefly limbless. These animals, which are sometimes placed as a separate branch of the squamates, are exceptionally specialized for a burrowing existence and use their strongly braced skulls to wedge into the substrata as they tunnel.

Although most lizards lay eggs (oviparity), representatives of many families have independently evolved viviparity (the bringing forth of live young). At least one skink (Family Scincidae) has a mammalian type of placental association between mother and young. Incubation period, clutch size and frequency of breeding vary by family, habitat, age and body size.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 771;