Characterization of Amphibians and Reptiles

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES ARE traditionally studied together and form the subject matter for the discipline of herpetology. This clustering is artificial in an evolutionary sense, since these two very different groups have been evolving independently for a very long time. The association of the two groups is based on their shared absence of features, such as feathers or hair, which characterize the other, more conspicuous, tetrapod lineages. Further, while amphibians and reptiles are very distinctive in regard to their genealogy, they do share a number of similar physiological and behavioural traits that are related to their particular modes of existence.

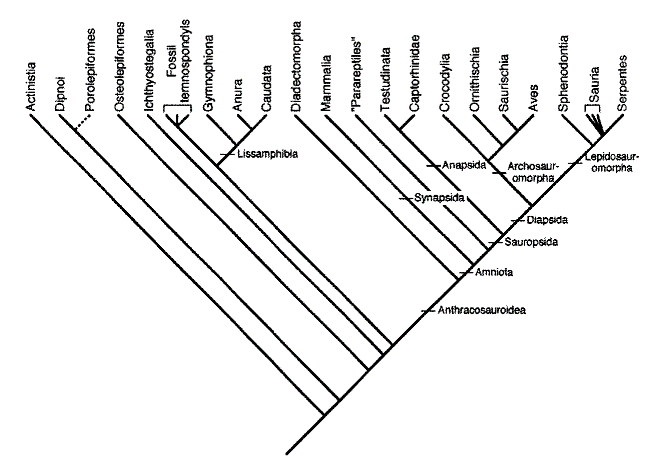

In the Devonian Period (about 400 million years ago) a group of freshwater bony fishes with a well-ossified vertebral column ("back-bone") and stout, fleshy limb-like fins gave rise to the stem amphibians, the first truly terrestrial vertebrates (Fig. 2.1).

These fishes, the osteolepiform rhipidistians, were somewhat similar in appearance to the living lungfishes and the coelacanth. All are members of a group of vertebrates collectively known as sarcopterygians. The early amphibians were in many ways quite dissimilar in appearance from those of today, but also displayed many common features. Throughout the latter part of the Palaeozoic Era and into the first part of the Mesozoic the amphibians diversified and exhibited a wide array of body forms and sizes. Only two of the many lineages of fossil amphibians gave rise to animals that survived to the present day. One group, the temnospondyls, are believed to have been the ancestors of the Lissamphibia, the group that includes all of the living amphibians. The second group, the anthracosaurs, are thought to have led to the reptiles, and ultimately, through them, to the other amniotes (birds and mammals).

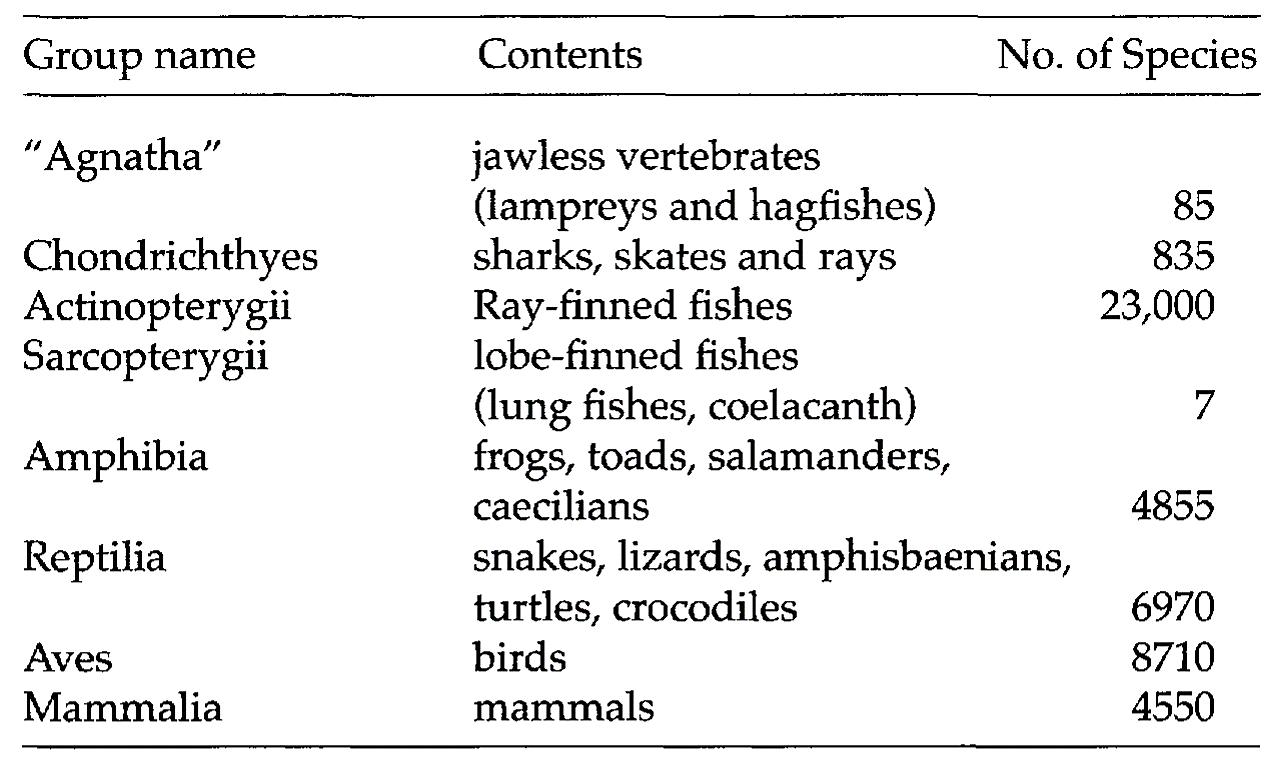

In all, there are about 49,000 living species of vertebrates and these are distributed among the following groups:

The term "Lissamphibia" combines the essential features of these living animals, referring to their typical biphasic lifestyle (living both in water and on land = amphibia) and their generally smooth (liss-) skin. Neither of these features, taken literally, characterize all members of the group, however, as among the almost 5,000 species currently recognized a great deal of variation in body form and lifestyle is seen. The features that were shared by the ancestor of all the living amphibians, and therefore serve to unite the group, are rather more subtle. Chief among these are characteristics of the teeth, skull, vertebrae, ribs, hearing apparatus, skin, eyes and musculature.

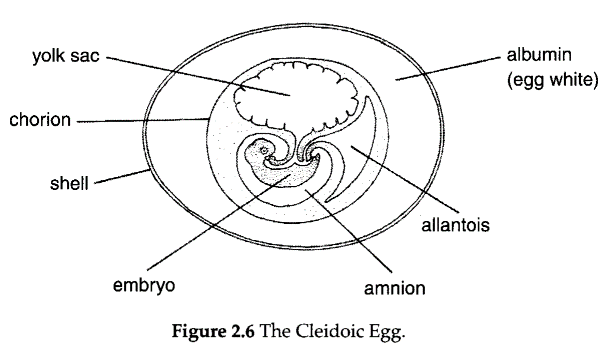

Some characteristics of amphibians are adaptations to life on land, others to life in the water. Their eggs are laid in water or in moist surroundings, and they are covered by several gelatinous envelopes but do not possess a shell or embryonic membranes other than the yolk sac (see Fig. 2.6).

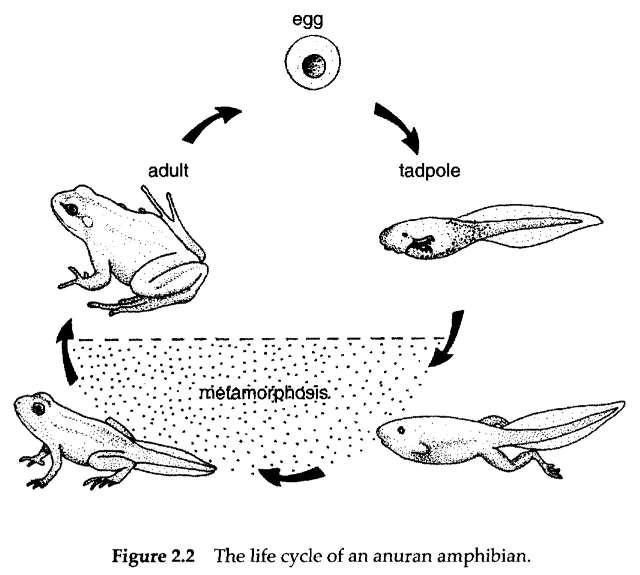

Extant amphibians retain a larval stage in their life history (Fig. 2.2). Thus, in most cases, the eggs give rise to a free-living "tadpole" stage that somewhat later metamorphoses to produce the definitive adult. In some species, the free-living larval stage is reduced or almost eliminated from the life cycle, but such instances are rare. The tadpole or larva is essentially an aquatic feeding machine and makes effective use of seasonally abundant plant life or prey items, depending upon the species, and thus permits a rapid increase in the biomass of the population. The food resources used by the larvae may be much different from those consumed by the adults, and at metamorphosis there may be marked changes in the gut system, as well as in external appearance, as the shift in diet takes place. The fact that amphibians have a larval stage has led to the belief that they are "chained to the water." This view, however, results largely from study of northern temperate amphibians, and many tropical forms show adaptations that enable them to develop, either partially or completely, in the absence of water.

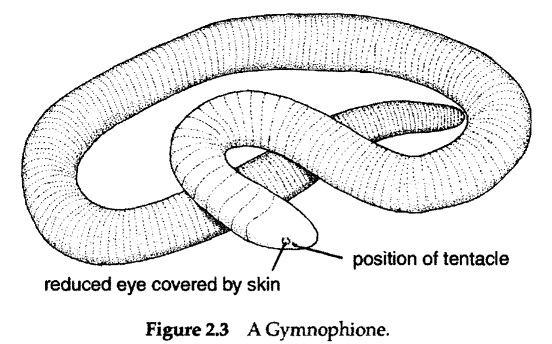

The living members of the Amphibia are divided into three major subgroups, two of which occur in Alberta. The least known and smallest group are the caecilians (Gymnophiona) (Fig. 2.3). These approximately 160 species of elongate, limbless animals are limited in their distribution to the tropical regions of the Americas, Africa and Asia. The caecilians are primarily burrowers, but some species are aquatic.

They feed primarily on insects, annelids (segmented worms) and other invertebrates. Although the eyes are usually reduced and often covered with skin or even bone, caecilians are able to perceive their external environment through a number of other sense organs including the tentacle, a small chemoreceptive device unique to the Gymnophiona. Caecilian eggs are usually few in number and heavily yolked, and in many forms the embryos are retained in the mother's oviduct for the entire embryonic period.

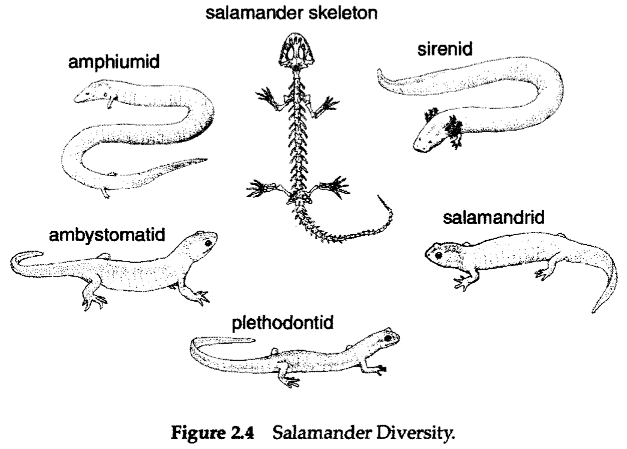

The remaining two groups of amphibians constitute the more familiar salamanders (Caudata) and frogs (Anura). The first of these is largely restricted to the Northern Hemisphere and achieves its greatest diversity in North America, where eight of the nine families are represented. Salamanders (Fig. 2.4) are characterized by: their generalized tetrapod body form, usually with four-toed fore feet and five-toed (pentadactyl) hind feet; metamorphosis from a well- limbed larva with external gills; long tail; teeth in both jaws; internal fertilization; and absence of external ears. There are approximately 390 species of living salamanders, ranging in size from the tiny neo- tropical Thorius (30 mm total length) to the giant aquatic salamanders of China and Japan, Andrias, which reach lengths of 1.8 m and may weigh more than 60 kg.

Although most are terrestrial as adults, many salamanders retain the features of the larval stage and are unable to metamorphose, maturing sexually and breeding as apparent juveniles—a phenomenon known as paedomorphosis (= childlike form). Some of these salamanders, such as members of the families Amphiumidae and Sirenidae, not only retain larval features, such as gills, but also show reduction of the limbs. Some other salamanders may utilize paedomorphosis as an option to overcome unfavourable conditions, but will metamorphose if and when conditions are appropriate and will reproduce as typical, terrestrial adults.

The best examples of facultative paedomorphs are shown by members of the family Ambystomatidae, which is the only group of salamanders found in Alberta. It is possible that this option is exercised by northern populations of the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) in Alberta. As in certain other groups of salamanders, ambystomatids have the ability to regenerate lost limbs or portions thereof, although this capacity is related to size, and larger individuals may lose this potential.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 763;