Catacomb Paintings: Progress in Style and Subject. The third part

The combination of pagan and Christian themes is found at its most striking in the attractive little burial-place lately re-discovered on the Latin Way and usually known as the Catacomb of the Via Dino Compagni. This has none of the higgledy-piggledy character shown bv many catacombs. The three shafts of which it is composed have the look, on plan, of an engineer's drawing, while much less space is taken up with galleries than with a well coordinated series of chapels.

Both the elaborate nature of these tomb- chambers and the quality of the painting indicate wealthy patrons, and emphasize the change which had come over Christian art by the middle of the fourth century. This change shows itself here in three ways. First, there is a wide variety of styles, corresponding to the ability and background of at least four groups of artists.

Secondly, a richness and amplitude about the whole place mark the establishment of the Christian faith in sophisticated circles, so that burial-vaults beneath the ground are built with elaborate cornices and all the architectural features which characterize the best type of mausoleum above ground. Thirdly, the conventional scenes drawn from the Old and New Testaments are handled with freedom and many new subjects are introduced; about a dozen appear here for the first time in the development of Christian art.

Most of the figures in the Biblical scenes are drawn with a marked economy of action and facial expression. Balaam, mounted on his ass, and the angel, looking like the typical philosopher, who bars his way with a dagger raised in the air, do not gaze at each other but are shown full face, confronting the spectator with round, dilated eves. The disciples listening to the Sermon on the Mount are shown rather more realistically in that, although their rounded heads and garments falling in vertical folds present a common pattern, they look intently towards the figure of Christ who, raised on the rock above them, dominates the scene.

The Samaritan woman at the well, though painted in a style resembling that of the Balaam episode, is more lively. The youthful Christ stands in an attitude of elegant mastery while the woman is so impressed that she ceases to draw her pitcher from the well and gazes at Christ in amazement from under her strongly- marked brows and neatly-dressed mop of black hair.

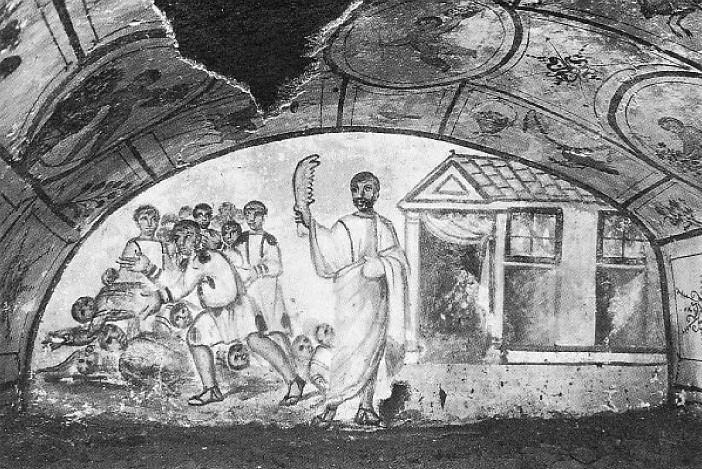

The lunette which shows Samson routing the Philistines with the jawbone of an ass is a still more vigorous composition (fig. 26). Here Samson stands in front of a house or shrine which occupies a third of the picture though it has no place in the story as given by the Book of Judges. He raises the jawbone in an attitude of poised, philosophic triumph while the Philistines flee in a rhythmically moving mass, their faces expressing with much individuality the emotions of fear and dismay.

26. Rome, Catacomb of the Via Dino Compagni. Wall-painting: Samson and the Philistines

Two crowd scenes, resembling one another in that they are similarly arranged over two panels set at right angles, present a contrast in method. The raising of Lazarus, no longer a matter restricted to Christ, the sister of Lazarus and one or two friends, has developed into a theme of world-wide application. Christ, shown as a young man barely distinguishable, except in size, from his companions, extends his rod towards the gabled tomb in which, however, Lazarus is not to be seen. Behind Christ is ranged a multitude of men, close-packed and attentive.

They narrowly resemble each other in clothing and posture; emotion is concentrated in their faces which, furrowed with dark, emphatic lines, show enough variety of movement to avoid the woodenness which might easily have marred so compact and stylized a company. But the other crowd scene, the crossing of the Red Sea, displays a more developed artistry. The little band of Israelites, painted in that pinkish purple which is the dominant colour in the picture, huddles to one side while the waters over which Moses stretches his magic wand form a central zone of unencumbered space before the jumbled but intensely dramatic onrush of the Egyptian cavalry with their blue helmets and long faces expressing horror at their impending doom.

A clearly differentiated group of paintings includes such Old Testament themes as Jacob’s dream and Abraham entertaining the three angels by the oaks of Mamre. Here the prevailing colour tends to be yellowish brown against a green background. The eyes, noses and mouths of the figures are robustly marked by thick lines of paint, while the rest of the face receives no emphasis; the hair falls, in a characteristic manner, amply and in a curving sweep from the crown of the head to the neck. The Mamre picture is notable for an elementary attempt to render perspective which causes the seated figure of Abraham to lean backwards and the three angels, wingless like those on Jacob's ladder, to incline forwards from what appears to be higher ground.

The Via Latina burial-place thus presents paintings of a quality unknown anywhere else in the catacombs for skilful technique, variety of subject and a richness of decoration which now and again comes near the sophisticated exuberance of baroque. The occurrence of the pagan themes confers an added interest. The winged genii are no more out of place than when they appear on a Christopher Wren screen, but the goddess Tellus (Earth), reclining on the ground amidst her flowers, with hand raised and a halo round her head, occupies the whole of the lunette above one of the tombs, which must be pagan, even though the peacocks above, birds of immortality drinking from the cup which holds the water of life, are found in Christian art also.

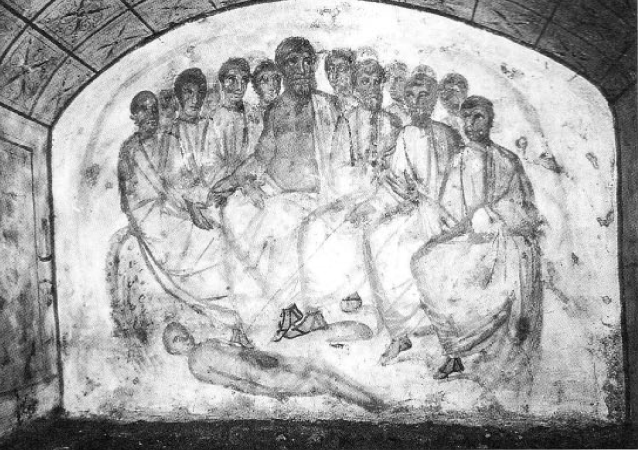

Another example of a mingling of pagan with Christian themes in the Via Latina burial-place is found in the chambers attached to the octagonal Room I. In one of the recesses Christ is shown, august and bearded, enthroned in majesty between Peter and Paul, who hold their scroll of apostolic authority. Nearby another niche contains a remarkable picture, of well-ordered and realistic classical style, which shows eleven men wearing the philosopher's customary garb and seated together in a row (fig. 27).

27. Rome, Catacomb of the Via Dino Compagni. Wall-painting: the philosophers and the dead boy

One member of this group stretches out his long wand to touch a small, naked figure lying on the ground in front of them all. This has been interpreted as depicting Aristotle’s achievement in withdrawing the soul from a boy's body and then restoring it with the help of a wand. If this explanation is correct, the pagan philosopher would in some measure correspond to the enthroned Christ in a mixed faith which takes something from both worlds. But the leader of this group sits in the centre; he is appreciably larger than the rest and he alone wears his pallium thrown back from the right shoulder in the manner of a Cynic philosopher but also typical of Christ as he is represented on some of the earliest sarcophagi.' The man with the wand is one of the disciples rather than the master, and the identification with Aristotle must therefore remain extremely doubtful.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 624;