Catacomb Paintings: The Image of Hercules, Moses and Turtura

Nothing, however, could be plainer than the events taken from the life of Hercules which are the sole theme of the paintings in the two niches of Room N. Hercules was the divine hero whose exploits were most particularly concerned with the conquest of Death. One of the most admired of his twelve Labours was the rescue of Alcestis, who had generously offered to die in place of her husband Admetus. Forcing his way past the monstrous dog Cerberus, who guarded the entrance to the lower world, Hercules raided Hell and brought Alcestis safely back to Admetus, a scene which the artist appropriately chose to illustrate in the catacomb. Nor is this surprising.

For, although the emperor Constantius ordered the closing of all pagan temples in the year 356, he was so overawed by the majesty of Rome when he visited it that he did little to enforce the principles which he had proclaimed and when, a little while later, Julian vainly attempted to substitute a revived paganism for Christianity, Hercules was put forward for imitation as a model of courage and wisdom. Thus people of conservative and patriotic temper, even if members of predominantly Christian families, might well choose to retain Hercules, an emblem of Rome's greatness as well as of immortality, beside the colourful incidents of the Bible story.

By the latter part of the fourth century interest in the catacombs was yielding to concern for churches above ground, though a few paintings of high quality exist here and there which reflect changes of taste observable in the mosaics and ivories. The Crypt of the Lambs in the Cemetery of Callistus presents a remarkable variation on the Moses story (fig. 28).

28. Rome, Cemetery of Callistus. Wall-painting: Moses

This painting, which dates from about 380, shows Moses in two scenes. On the left he is removing his shoes in obedience to the command given from the midst of the burning bush; here he appears as a young man with long face and rounded head. But just alongside occurs another figure of Moses, striking the rock and drawing from it a copious stream of water towards which a soldier hastens with flying cloak. In this second portrait he is shown bearded and with a mass of long, curly hair. The highlight on his nose is emphasized by the dark vertical line at each side and his eyes, brilliant but deep-set, express awe and foreboding at a miracle which he feels obliged to perform but at the cost of incurring God's anger.

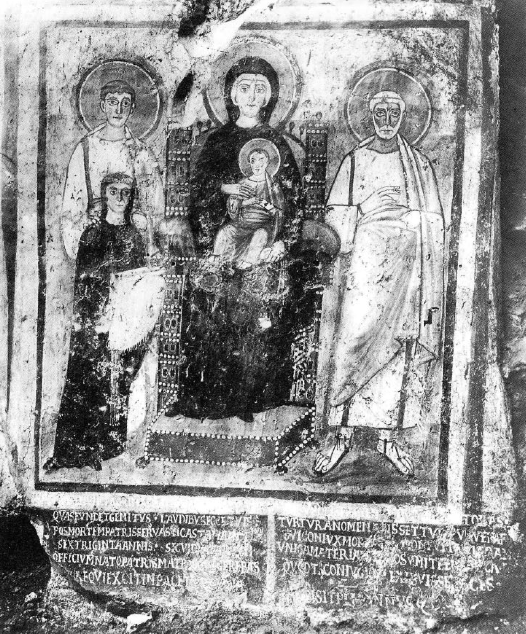

The chapel constructed in the Catacomb of Com- modilla to the honour of the martyrs shows the final stage alike of thought and style. Eyes are no longer round but almond-shaped, faces are elongated and thin, hair is so tightly drawn down over the head as to look almost like a helmet and haloes9 are a regular embellishment of all saintly persons. Realistic portraiture entirely disappears and the solemn, timeless atmosphere of Byzantine art prevails. One notable example of this transition is the painting which commemorates a certain Turtura (fig. 29).

29. Rome, Catacomb of Commodilla. Wall-painting: Virgin and Child with Turtura

This woman is being presented by two saints, Felix and Adauctus, to the Virgin and Child, but the mood is one of abstract dignity. The martyrs, one young, the other old, stand at either side of the Virgin's richly jewelled throne and, like all the figures, look straight ahead. Both are motionless except that Felix places one hand on Turtura's shoulder while Adauctus raises his hand in passionless assent. The Virgin, in her long, purple robe, has become an empress, calm and unmoved save for the protective gesture of her right hand with which she holds the Child seated in priestly costume on her lap. The art of the catacombs has advanced a very long way, in three or four centuries, from the primitive sketches of shepherd, anchor or fish.

Motives of ease and economy gradually caused catacombs to become unpopular for burials except near the shrines of martyrs, and, in the commotion caused by the onslaught of Goths, Vandals and finally Lombards, it was judged expedient to transfer the bones of martyrs to churches above ground, a move which led to complete oblivion and neglect for the subterranean tombs. But before these events, about the year 370, the zealous and turbulent Pope Damasus had, with his habitual energy, carried out many works of restoration and improvement to those burial-places where the martyrs rested. He widened passages, constructed new staircases and inserted light-shafts to make access and devotion easier for pilgrims, as well as beautifying certain sanctuaries with marble.

But his greatest achievement was to compose a set of versified inscriptions in honour of the martyrs and to employ a craftsman of the highest skill, Furius Dionysius Filo- calus, to carve these inscriptions on marble slabs. The lettering, subsequently copied by such artists as Eric Gill, is of exceptional grace and clarity, which is more than can be said of Damasus' poetry itself. The pope showed much perseverance in tracing the stories of the martyrs' lives, even if he sometimes allowed his enthusiasm to outrun his critical judgement, but he was inclined to summarize his researches in language so vague and verbose as to obscure his meaning.

Pilgrims to the shrines diligently copied Damasus' pedantic hexameters and thus it is often possible to complete fragmentary remains of the originals. One set of verses, found on the Vatican, runs thus:

The waters surrounded the hill and in their slow wandering soaked the bodies, the ashes and bones, of many. Damasus could not allow that those who had been buried, in the destiny that falls to all, should in their repose be obliged to suffer a second time so sad a fate. Straightway he set about undertaking a heavy task: he threw down the towering peaks of the vast hillside and examined with anxious care the inmost entrails of the earth. He dried all that the water had drenched and discovered the fountain which offers the grace of salvation.

A rather less fulsome instance of the same style of composition is provided by an inscription derived, with the help of a later copy, from fragments found in the Crypt of Hippolytus on the Tiburtine Way:

It is said that, although the tyrant’s commands were oppressing us, the priest Hippolytus continued in the schism of Novatus. But at the time when the sword rent the very heart of our Mother the Church, then in his devotion to Christ he sought the kingdom of the just and when the people asked which way to turn he bade them all follow the catholic faith. Having thus borne witness to the truth he deserves to be called our martyr. It is Damasus who records this tradition but Christ who brings all to the test.

The Spanish hymn-writer Prudentius speaks of this particular crypt in words which would serve to describe many catacombs and the emotions of those who descended into them:

Not far from the city rampart, in the open farmland, the mouth of the crypt gives entry to its murky pits. Into its secret recesses a steep path with curving stairs guides the way, while its winding course bars out the light. The brightness of day comes in, however, through the opening at the top and illumines the threshold of the entrance-hall. Then as, by gradual advance, you feel that the darkness of night is closing in everywhere through the mazes of the cavern, there occur openings pierced through the roof which cast bright rays about the cave.

Although the passages cut at random w’eave a pattern of narrow chambers and murky galleries, yet, where the rock has been cut away and a vault hollowed out and pierced through, light makes its way in abundantly. To such secret recesses the body of Hippolytus is entrusted hard by the place where an altar is dedicated to God and set up. The same altar-table bestows the sacrament and faithfully guards the martyr's bones. Now the shrine which encloses the relics of that brave soul gleams with solid silver. Wealthy hands have set in place a smooth surface of glistening panels, bright as a mirror and, not content to overlay the entrances with Parian marble, have added lavish gifts for adorning the whole place.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 706;