History of the catacombs in the Vatican. Continuation

Four other sarcophagi are contained within the Tomb of the Egyptians. One is a plain and humble affair made of terracotta. Painted inside the recess where this coffin lies are the figure of a woman and a fragmentary inscription including the word deposita ('laid to rest'), a Christian formula confirmed by the Christian symbols of palm-branch and dove. In this tomb, then, the three emblems of Horus, Dionysus and Christ declare a common message of undying hope.

The burial-place, however, which provides the classic example of a transition from pagan to Christian uses is the diminutive Tomb M, approached by a short passageway from the north side of the street. This tomb was constructed during the second century for the family of the Julii. In addition to the evidence of cremation, the epitaph, now lost, of a child named Julius Tarpeianus bears witness by its form to pagan beliefs. But either the Julian family became Christian or they rendered up their mausoleum to another family, which held that faith and saw fit to decorate the ceiling and top portions of north, east and west walls with pictures made up from the little cubes of opaque glass known as 'mosaic'. Some of the cubes have fallen from their place and disappeared; they have, however, left impressions in the plaster which held them and on which the designs had been painted in fresco for the mosaicist to follow.

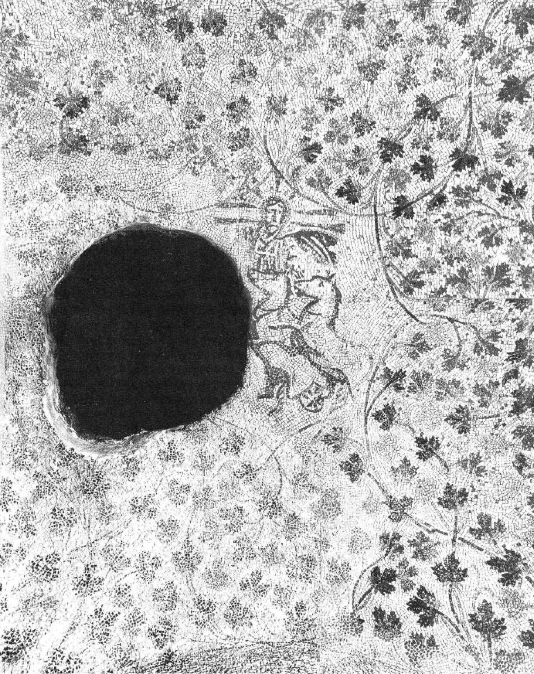

The subjects shown on these walls are typical of the funerary art of the third century: Jonah falling into the whale's mouth, the Good Shepherd, and the Angler fishing for souls in the waters of baptism. But on the ceiling, where fortunately the mosaic is in large part preserved, occurs a more striking figure that owes its form to pagan models. Within a framework of vine- leaves—some light, some dark, but all brilliant green—Helios, the Sun God, ascends heavenwards in his chariot drawn by two prancing white horses (fig. 22). Behind his head is a halo, from which rays of light shoot forth, but their arrangement powerfully suggests a cross, and, in this Christian context, it proves that the figure is in fact not Helios but Christ,’ the Sun of Righteousness, arising, as the hymn says, to 'triumph o'er the shades of night'.

22. Rome, the Vatican, Tomb M. Mosaic showing Christ as the Sun of Righteousness

A little further west the row of dignified sepulchres gives place to a confused scattering of humble tombs, and it is here that the 'Shrine of St Peter' is to be found. The tradition which held this to be Peter's burial-place was sufficiently strong, early in the fourth century, to present the emperor Constantine with great practical difficulties in constructing his majestic church on a hilly and inconvenient site from which, moreover, at the risk of causing considerable offence, he had to remove a number of existing tombs. But the excavations which have in recent years been carried out beneath this venerated spot have failed to discover any obvious tomb of St Peter, still less his body lying in a large coffin of solid bronze to which reference is made in the earliest official biography of the Roman bishops.

What has been found, at the central point now marked by Bernini's great canopy, could be described as a shrine, but it is one which leaves many questions unanswered. Set amidst a cluster of tombs, one or two certainly pagan, others possibly Christian, runs the so-called Red Wall, which can be dated with very fair assurance to the period 160-70 ad. Built into this wall, and contemporary with it, are the remains of a structure consisting of three niches, one on top of the other and resembling, in general architectural style, the inscribed monuments which were sometimes added to the front of grandiose tombs. In this case the two upper sections, slightly over two metres in height, seem to have looked like a diminutive altar, with a marble slab, supported on two small detached columns, separating the niches.

The columns, in their turn, rested on another slab of marble, below which is a rectangular recess which may be seen as the third niche, usually held to be later than the rest of the structure, and cut into the Red Wall when this had already been built. The recess when discovered contained nothing but rubble; but nearby, under and at the back of the Red Wall, human bones were found—no very surprising discovery to make in a cemetery area. The suggestion has been put forward, reasonably but not with complete assurance, that this niched structure is the 'trophy' of Peter on the Vatican Hill mentioned by the presbyter Gaius.

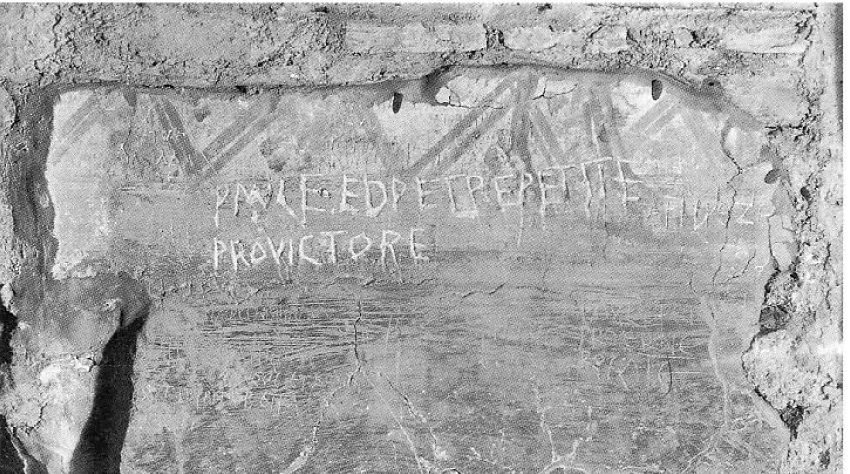

The little shrine which Constantine made the focal point of his basilica may or may not have been Peter's 'trophy'. That it was regarded, at least by the end of the third century, as a place of pilgrimage is witnessed by the large number of graffiti scratched on the walls nearby. These inscriptions are, however, simple prayers on behalf of relatives—'Nicasius, mayest thou live in Christ', and so forth—without any reference to Peter, except one short appeal, written in Greek, which alludes to a Peter who is by no means certainly the apostle. This is in marked contrast to the numerous invocations of both Peter and Paul found in the Catacomb of Sebastian: 'Peter and Paul, remember us', 'Paul and Peter, pray for Victor' (fig. 23) and many more of similar type.

23. Rome, Catacomb of Sebastian. Inscription: 'Paul and Peter, pray for Victor'

That the apostles were here called upon for aid in a shrine frequented by simple pilgrims has led to the fanciful theory that the bodies of Peter and Paul were moved to a crypt in San Sebastiano during a persecution carried out by the emperor Valerian in 258 ad and subsequently returned, in the time of Constantine, to their proper resting-places on the Vatican and on the Ostian Way. It may indeed be noted that the Calendar of Filocalus (354 ad) records festivals of Peter on the Vatican, Paul on the Ostian Way and both 'in the catacombs', that is, in the Catacomb of Sebastian.

Of this particular cemetery Pope Damasus I stated, in an inscription now known only from medieval copies: 'Anyone who is enquiring about the history of Peter and of Paul likewise must understand that the saints dwelt here once upon a time.' By 'dwelt' Damasus meant 'were buried', but this evidence comes from the latter part of the fourth century, and a crabbed reference in the Filocalian Calendar to events in 'the consulship of Tuscus and Bassus' (238 ad) is far from clear. It may mean only that, in the distressful times of Valerian, celebrations in honour of Peter and Paul were initiated and the aid of the apostles invoked.

The evidence of archaeology concerning St Peter may therefore be summed up concisely, though in a manner which leaves much detail uncertain. Peter was honoured, together with St Paul, in the Catacomb of Sebastian, and it appears that some may have supposed that this was his place of burial. On the other hand, his name is closely connected with the Vatican, where a monument to him was pointed out as early as 200 ad. The precise nature of this 'trophy' can hardly be determined, but it may very plausibly be identified with the niched structure, now rather fragmentary, which Constantine made the focal point of his great church and which remains so today. Of Peter's grave, as such, no trace remains, nor did Constantine leave any record to say whether he interpreted the shrine as marking the site of Peter's tomb. Nevertheless, as in Palestine, so in Rome the emperor clearly went out of his way to mark by a building of much splendour one of the sites hallowed by local tradition.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 913;