India, Ancient — Indus Valley. The Extent of the Indus Civilization’s Trade Contacts. Geography and Climate

The Indus civilization arose within the greater Indus Valley of Pakistan and northwestern India in the middle of the third millennium все. Its dates have been set using the radiocarbon method and cross ties with Mesopotamia to 2500-1900 все.

This period saw the emergence of the great Indus cities of Mohenjo Daro, Harappa, Dholavira, Ganweriwala, and Rakhigarhi. The cities, towns and villages of the Indus civilization were inhabited by diverse peoples who lived in a stratified society, engaged in craft and career specialization, and knew the art of writing.

The Extent of the Indus Civilization’s Trade Contacts. The Indus peoples had far reaching contacts with Mesopotamia, the Arabian (Persian) Gulf, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran. Much of this interaction was based on the trade of exotic products and raw materials: items made of lapis lazuli, carnelian, copper and bronze, woods, shells, pearls, and the like. In addition to the overland exchanges, we know that the Indus folk were also seafarers.

Mesopotamian cuneiform documents of the third millennium speak of maritime contact with Meluhha, reasonably associated with the Indus civilization. There are scores of sites in the Arabian Gulf with Indus pottery and other artifacts, including stamp seals with Indus writing. The remains of maritime fish and shells are represented at Indus civilization sites.

This maritime activity apparently extended to the import of plants to the Indian subcontinent. Millets like sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet, native to subSaharan Africa, were introduced there in the third millennium. Seafaring Harappans who reached the mouth of the Red Sea apparently brought these plants back to the subcontinent.

Geography and Climate. The environment of the greater Indus region is, and was, diverse. Millennia of degradation by man and domesticated animals have brought measurable change. There is no systematic, well-documented environmental reconstruction for the Holocene epoch (the past ten thousand years) in this part of the world. The sense one gets is that tree cover in the region was greater and probably more diversified in prehistoric times. Similarly, the grasslands and savannas were more lush and richer.

The river system was considerably different in the third and fourth millennia все from the one we see today. In the fourth and third millennia все there was a major river flowing out of the Siwalik Hills southwest toward the Indus Valley. This is known as the Sarasvati. A second river, the Drishadvati, joined it near the site of Kalibangan.

At that time the Yamuna River was a very small stream. The tectonics of the subcontinent led to changes in the watersheds of these rivers that led to the growth of the Yamuna at the expense of the Sarasvati-Drishadvati system. The Drishd- vati dried up in the fourth millennium, its waters going to the Yamuna, which grew in size over this time. The Sarasvati was largely dry by the beginnings of the first millennium все.

The precise course of the Indus River during the Indus civilization is not known, but studies of palaeo- channels show that it is likely that the channel was to the west of the city of Mohenjo Daro, nearer the foothills of Baluchistan.

The climate of the greater Indus region was entirely stable during the Holocene. There was most likely variation in both the monsoon (June to September) and the winter westerlies that bring rain to the western portions of the Indus civilization. But the evidence for real climatic change (as opposed to variation) is weak.

There is insufficient evidence to say that at any point during the Holocene there was enough change in rainfall, for example, to have had a measurable effect on crop yields and the production of grasslands for pasture. (The researchers Singh, Wasson, and Agrawal take a dissenting view in their 1990 article published in Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology).

Domestication of Plants and Animals. The key site on the subcontinent for evidence of the early domestication of plants and animals is Mehrgarh, where a settled village community is in evidence in the sixth or seventh millennium все. The peoples of Mehrgarh in Period I (7000-5000 все) had three forms of domesticated barley and three forms of domesticated wheat, with the barley representing more than 90 percent of the food grains recovered in excavation.

The noncereals so far identified for the period include the Indian jujube and dates, represented by stones in Periods I and II. There is also a possibility that cotton was cultivated in the Mehrgarh area at an early date (Period II, 5000-4000 все). Cotton fabric was preserved at Mohenjo Daro (2500-1900 все).

Humped zebu cattle, a native species, was domesticated at Mehrgarh, native sheep and goats may also have been domesticated. Wild forms of all three of these animals are found in the vicinity of Mehrgarh. This suite of domesticated animals was of fundamental importance to population growth and diversification in the greater Indus Valley, which eventually led to urbanization and the Indus civilization.

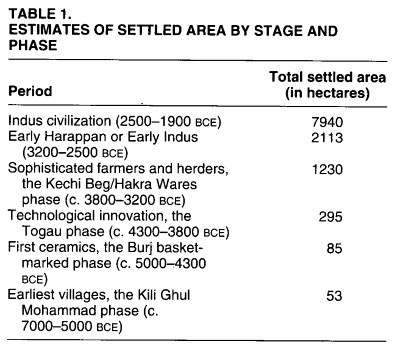

Sustained population growth in the greater Indus region cannot be directly observed, but by adding up the size estimates for sites from successive periods in the prehistoric Indus region we get a sense—not very precise, of course, but a rough estimate—of "size." This is not the total "size" since there are many sites yet to be discovered, and some sites have vanished from view, or all together.

Moreover, on sites with long-term occupation through many periods, size changes within each period is a critical factor. There are reasons to suggest that these factors apply equally to all sites in each of the archaeological periods that have been defined for the eras prior to the Indus civilization. This being so, one should then look not at the size figures per se, but at the changes between them to see long-term changes in population. (See table 1.)

Date added: 2023-08-30; views: 897;