Democracy in Ancient Greece

Democracy is a form of government in which the people directly decide on issues facing a political unit. In ancient Greece, the best and clearest example of this was in Athens, especially during the fifth and fourth centuries. Athenian democracy arose due to the political inadequacies of the earlier reforms instituted by Solon in the sixth century. His reforms brought about a political system based primarily on wealth, with the top political offices going to those who had the largest and most stable sources of income (usually land).

This led to discontent, especially among the city’s middle class, and helped propel Pisistratus into leadership as the tyrant during the mid-to-late sixth century. With the ouster of Pisistratus’s son Hippias in 509, Athens called upon one of its leading citizens, Cleisthenes, to establish a new system of government.

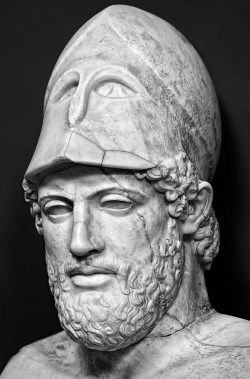

Bust of Pericles. (Abxyz/Dreamstime.com)

Cleisthenes recognized that Athens was faced with social and political inequalities based primarily upon the geographical distribution of its population. Those that lived in the coastal region or plains had extensive holdings in agriculture, producing a segment of the population that was conservative but wealthy.

Those that lived inland in the mountain or hill regions were often poor, with small land holdings; they also supported Pisistratus as he promoted new opportunities. Finally, there were those who lived in the city, who were often merchants but also included the urban poor, who desired entrance into the political monopoly held previously by the wealthy.

Cleisthenes realized that all three geographical areas had to be integrated into political life somehow to prevent the regional factionalism that had occurred during the previous century. The democracy of Athens would undergo a series of changes, mostly related to how the officeholders were chosen. In the earliest system, Cleisthenes still envisioned that each office would be filled by election. Later, this was sometimes changed to selection by lot.

Cleisthenes decided to use preexisting political forms as the basic building blocks and then add new entities where needed. He used the preexisting 139 demes as the first entity. These were geographical regions, small towns or hamlets, that were spread out across Attica, the geographical region of Athens and its surrounding territory.

The city itself had five demes. A deme classified as part of the city may not have actually been in the city but may have had some kind of close connection to it. Each deme varied in geographical size and population; some were small, with only a few hundred people, while others were large, approaching thousands. Cleisthenes ordered that all of the citizens be enrolled in one of the demes. Most likely, they were enrolled in the deme where they currently resided. What makes Cleisthenes’s reform crucial is that from then on, the descendants, regardless of where they lived, were always enrolled in the same deme as their ancestors.

In this way, if someone enrolled in one of the inland demes moved into the city, they and their descendants would still be a member of the inland deme. It is clear that Cleisthenes did not attempt to make each of the demes equal in population, probably because it would have disrupted the social fabric and continuity of the entire region.

Cleisthenes then created the trittyes, plural of trittys, which means “a third” in reference to the three types of land. He created ten trittyes for each of the three districts so that in total, there were thirty trittyes—ten for the city, ten for the coast, and ten for the inland (mountains or hills). The role of the trittys is unclear, other than acting as a bridge between the numerous demes and the few tribes. It may have been created as a way to bring disparate and nonadjoining demes from each region into the political system at the local level, without having much dissension.

The trittyes were composed of at least one deme, and there were usually more in each region, and those with multiple demes may have had their members based not on their proximity to boundaries, but to roads, allowing ease of communication. The trittyes may have played a part in military matters with the outfitting and organization of ships and the army. They typically derived their name from the largest deme in the trittys. With the demes then allocated to each of the trittyes, it is clear that each trittys did not have the same population; again, this may have been due to Cleisthenes desiring to have the next level, the tribes, as the averaging factor.

To ensure political stability, Cleisthenes then took one trittys from each of the three regions to create one tribe. In this plan, the thirty trittyes would create ten tribes, an increase over the four tribes created by Solon. It is probable that Cleisthenes determined that the varying-sized demes and trittyes would be averaged out in the new tribes. The tribe would now become the crucial element of the political system. All political offices were increased to ten—one for each tribe.

Competition was no longer among tribes, but rather within tribes. Individuals ran against members of their own tribe for office. In his plan, the geographical variations were now intermixed with the trittyes and the tribes. For example, two neighbors belonging to two different demes may be enrolled in two different trittyes. They would then be enrolled in two different tribes as well so that they could not vote for the same political officers.

At the same time, candidates could no longer attempt to create a power bloc from their own region. For example, a candidate from one region for an office in one tribe would need to get the support of the two other regions. A candidate from the city would need to get support from the demes in his tribe and the trittyes from the coast and inland. His competitor may not have been from the same region and would also need to get support from the other regions. In his system, Cleisthenes forced the three geographical regions to work together.

For Cleisthenes, everything revolved around the selection of officials from each tribe. This included the boule or council. When Solon reformed the Athenian constitution, he created a council or boule of 400; this group was made up of exmagistrates normally drawn from the upper class, with 100 representatives from each of the four tribes. Cleisthenes kept that framework but adapted it to his new system. Instead of 400 members, the boule would now have 500, with 50 members selected from each tribe. In addition, since the Athenian year was divided into ten months, each tribe was responsible for running the boule for one month. These councilors, or bouleutai, came from the various regions and demes. It was not an exact division; the city gave 130 members, the coast had 196, and 174 came from the inland.

It is unclear as to why there were these differences, but since the constitution remained unchanged for over two centuries, it must have worked without anyone objecting too much. It appears that by the mid-fifth century, and probably extending back to Cleisthenes’s original reform, members of the boule were selected by lot, without an election. In the later period after 450, individuals could serve on the boule no more than twice in their lifetime, and never in successive years. It is probable that Cleisthenes instituted the requirement that no one could serve more than once, and that this rule was relaxed during and after the Peloponnesian War, when the number of citizens was reduced.

As with all members of the citizenry eligible for holding office, one had to have a certain specified amount of property and wealth, although this sometimes seems to have been ignored later. Members of the boule began to receive pay in the 460s, after the reforms of Ephialtes and Pericles; it amounted to 5 obols for a regular member and 6 (or one drachma) for the prytaneis, members of the standing committee of the boule. Assuming that one served twice (which was not guaranteed), the number of citizens needed to serve in a twenty-five-year period would be 6,250 and more likely 10,000, showing how successful the system was in terms of bringing about broad representation of the citizenry.

Taking office in midsummer, the council members were granted honorific places in public celebrations and exempt from military duty; they were, however, required to stay in Attica and meet every day, except for holidays and days of bad omen, in the bouleuterion, or Council House, near the Agora. Most likely, one received pay only if they attended that day’s meeting. Members could speak in the meetings, although no one seems to have been forced to participate.

Each tribe served for one month as prytaneis, whose job it was to keep the agenda and run the meeting; the order was determined by lot. One of its members was chosen each day by lot to be its president, or epistates, and was in possession of the state seal and keys to the treasury; a person was limited to holding this office only once in his lifetime. The prytaneis received envoys and messengers.

The ultimate authority for the political life of Athens was the assembly, or Ecclesia. In theory, this body was composed of all Athenian citizens. On any given day when the assembly met, its total number of members probably only approached 6,000 at most, but that was still a sizable number. The constitution of Cleisthenes also had a safety valve—the idea of ostracism, in which an individual could be banished for ten years if the assembly voted as such. During the early period, the use of ostracism was commonly used as a way to get rid of antidemocratic elements.

The boule would debate proposals and other ideas and then present them to the assembly. To have something put on the agenda for the assembly, any officer of the state, council member, or even any citizen could come before the boule and make a proposal or proboulemata. The proposal could be precise, such as an honorific decree, or an open question on an important subject. It might be controversial, such as to wage war or make peace, but many were probably routine matters.

The boule was also involved in state finances, something that took on more prominence during the fifth century, when Athens achieved its naval empire. Although always subject to the assembly, the boule had extensive leeway in its judgment. Its members constituted the primary overseers of the state offices, especially when it came to their expenses.

One of the problems with the Athenian system, which gave the boule even more power, was that since officers and boards were selected by lot and usually not able to repeat service, there was high turnover, meaning that most of these people did not have a full understanding of the system and the intricacies involved in state finances. The boule and those who regularly interacted with it could use this lack of knowledge to their benefit.

The boule would appoint a board of ten auditors from the prytany as auditors to examine the accounts of each official. In later times, individuals were elected to serve as financial officers, and they could be reelected yearly to oversee the important military and civil funds. In some ways, the boule was powerful since it oversaw so much of Athenian politics and social life. However, at the same time, it was not that powerful because its membership constantly changed and that prevented one individual or group from holding much power or influence.

Cleisthenes’s constitution was continually altered. The major reforms occurred during the mid-fifth century, led by Pericles and Ephialtes. The latter was an opponent of Cimon (an anti-Persian general), who not only attempted a rapprochement with Persia but also wanted to make Athens even more democratic. He introduced attacks against individuals in the Council of Areopagus, which was a holdover from the earlier pre-Cleisthenes government.

It was made up of exarchons, creating a Council of Elders. It was originally established as a check on the monarchy and it later became a court of justice, ruling on cases of murder and manslaughter. It soon became the governing body for the city of Athens during the aristocratic government. The Council of Elders seems to have had some control over the election of magistrates, even though the archon and polemarch were elected by the Assembly.

It is possible that the council vetted the candidates first. These members were also in charge of punishing public officials if they violated the law, as well as of general administration of the laws and overseeing the working of the government. These were powerful checks not only on the people, but on the government in general. Ephialtes brought a series of lawsuits against individual members of the Areopagus and ultimately got a law passed stripping the Council of Elders of most of its oversight of the laws and government.

The council ultimately had jurisdiction only over cases of homicide and caring for the sacred olive trees of Athena, and it also had a say in the supervision of the Eleusinian property. The other responsibilities passed to the Council of 500, the Popular Assembly, and the law courts. This attack on the Areopagus was followed by an attack on the office of the Archon. Archons automatically became members of the Areopagus, and this was seen as an honor.

Previously, the office was unpaid, with its holders coming from the upper two classes. In 458 BC, when the attack on the Areopagus occurred, Ephialtes and/or Pericles moved to make the office of Archon a paid position. This meant that members of the third class were now eligible. Further changes made all of the offices chosen by lot. Previously, there had been a mixed system in which members were chosen by lot after an initial election into a pool, but this was now eliminated, and all but a very few numbers of offices (mainly military) were chosen by lot.

Ephialtes was successful in banishing Cimon through ostracism, but he in turn was assassinated, perhaps due to the ostracism or more likely political rivalry in his own faction. In addition, the system was altered so that pay was expanded for other positions and was introduced by Pericles, including for jurors and perhaps those who attended the Assembly.

Since jurors and perhaps those who attended the Assembly were now paid, it became an incentive to keep the number of Athenians constant to ensure enough citizens but not too many as to tax the system financially. This whole process was accomplished by a new law in 451 that restricted citizenship to those whose parents were both Athenians. If this law had been in place earlier, Cleisthenes, Themistocles, and Cimon would have been excluded.

Many of these changes occurred when Athens transformed the Delian League into an empire. When the treasury of the league was moved from Delos to Athens in 454, Athens had complete control over the league’s finances, which allowed it to pay for political offices, juries, and ultimately the rebuilding of the city. The democracy of Athens was therefore tied closely with the Delian League, and later the Athenian Empire. The democracy of Athens proved that decisions could be made by the people, regardless of their class.

Date added: 2024-08-19; views: 494;