Etruscans. Greek interaction with the Italian region

Greek interaction with the Italian region centered on two main cultures, Carthaginian in the south and Etruscan in the north. Contacts with the Etruscans go back to the early post-Mycenaean period, when Greek traders, operating since the early Mycenaean period, continued to trade with the local Italian inhabitants, especially buying tin used in the making of bronze. In northern Italy, the Etruscans became one of the dominant political forces in the region.

People’s interactions with the Etruscans varied depending upon the situation and the period. When the Greek states engaged in trade, the Etruscans had good relations with them, but when they began to form colonies in Italy, the Etruscans took that as an attempt to reduce their power, which often led to political and military disputes.

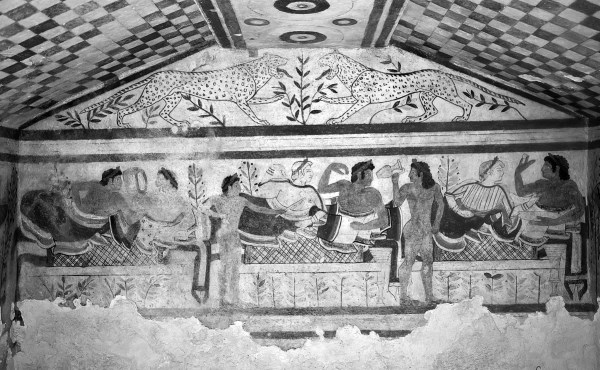

Etruscan tomb painting. (Perseomedusa/Dreamstime.com)

The Etruscans inhabited the part of Italy mainly north of the Tiber River to the Arno River, corresponding to the modern region of Tuscany. Their origins are clouded in mystery, with ancient authors differing about where they precisely came from. In the fifth century, Herodotus indicated that they came from Lydia in Asia Minor and migrated to Italy before the Mycenaean or Heroic Age, while during the Roman period, the antiquarian Dionysius of Halicarnassus stated that they were indigenous to northern Italy, a view currently supported by archaeological evidence. The reason for Herodotus viewing them as immigrants stems mainly from their language, which was different than that of the local Latins, forerunners to the Romans.

Etruscan language, culture, and political development clearly distinguished these people from the Greeks, and even from other Italians. Archaeology helps explain and elaborates on Herodotus’s view of the Etruscan culture. Their proximity to the coast allowed interaction with the Greeks, and the major Etruscan cities were at Caere, Tarquinii, Veii, Volaterrae, and Vulci. It appears that the Etruscans then moved inland, establishing cities at Arretium, Clusium, and Perugia in modern Umbria in the Tiber valley.

They then spread eastward beyond the Apennines. Support for the idea that the Etruscan language was indigenous can be seen from their cultural remains, which were unbroken from the earlier Italian Villanovan or Iron Age culture in Etruria; this attested that their origin was not from immigration from other parts of the Mediterranean. Their tombs, however, show a sudden influx of Greek material or influence, probably from their commercial interactions, and this may show a willingness of the elites to accept new and foreign ideas. It is not clear if the general population followed suit or if Greek culture prevailed.

The various cities and tribes were independent during the immediate post Mycenaean or Heroic Age, but by the seventh century, they had consolidated into the society now called the Etruscans, where they had developed their own distinct culture and beliefs. Archaeology provides the clearest examples of their cultural remains, especially in tombs that contain jewelry, sculpture, and paintings. These paintings, especially from the city of Tarquinii, show a cultural view that differed from Greek culture, where the Underworld is dark and fatalistic.

Rather, the Etruscans show scenes of banqueting, music, hunting, racing, and dancing, promoting a general sense of merriment. Herodotus in his description indicated that men and women were often together in public, indicating that the latter had a higher social status than in Greece. For example, Etruscan women were permitted to sit next to their husbands at banquets, own personal possessions, watch sporting events with men, inherit property, and even retain their own surnames when married. These scenes are represented in sculpture and grave paintings and may in fact point to a more liberal view of women by the Etruscans than by the Greeks— one that Herodotus found alien and distasteful.

In the area of craftsmanship, their products, especially jewelry, metalwork, and household goods, circulated throughout Italy and were greatly admired. Examples include the famous She-Wolf in Rome, symbol of the Roman state used throughout its history (and even today) and the Chimaera of Arezzo, (a fire-breathing creature), a bronze statue that some art historians have indicated is the best example of Etruscan art; especially noteworthy were their terra-cotta creations, many of which adorned their temples.

The Spartans exported pottery to Etruria from the mid-sixth century until the mid-fifth century. After this time, they did not expand on their arts as other cities did. After Sparta’s contact with the Etruscans diminished, Athens took over, supplying the Etruscans with red-figured pottery, reaching as far north as the Po River valley. The Etruscans supplied Athens with metalworks.

The Greeks after 600 attempted to establish more colonies in the west, which led them to conflict with the Etruscans. Allied with the Carthaginians, the Etruscans did not wish to see an increase in Greek colonies in central and northern Italy. The Phocaeans, who had colonized Massalia (Marseille), also pushed for more colonies in Spain and on Corsica at Alalia. The Carthaginian and Etruscan fleet destroyed the Phocaean fleet off Alalia in 535; although victorious, the Phocaeans had lost a large number of ships and decided to evacuate the island of Corsica and sought refuge in Rhegion in southern Italy. The Etruscans took over Corsica, while Carthage controlled Sardinia. The Etruscans prevented Greek settlements from moving into the north of Italy, while maintaining trade associations with both Carthage and the Greeks via the southern cities.

It was mostly in their political life that the Greeks came into contact with the Etruscans, who had dominated northern Italy by the seventh century and in the sixth century began to move south of the Tiber River into Campania, where they established the city of Capua around 600. Unlike the completely independent cities of Greece, the Etruscans had a confederation of independent cities based upon a common religious system centered at Volsinii. Around 550, they reached the zenith of their power, controlling most of the Italian peninsula from the Po River in the north to Capua in the south; this even included Rome, where they had even taken over the monarchy.

The last Roman kings were the Etruscan Tarquins, who were driven out in 509. Their power began to wane soon after a naval battle off Cumae in 474, when the Greek forces of Syracuse and Cumae combined to defeat them. Cumae had been founded in the eighth century just south of the Etruscan border and was in constant conflict with the Etruscans. In 504, Cumae defeated the Etruscans, but they still retained power and raised a fleet in 474 to retaliate against Cumae. Hiero I of Syracuse received a request from Cumae, and together with other Greek cities, he moved to keep the Etruscans out of the Bay of Naples.

The defeat at Cumae caused the Etruscans to lose their preeminent influence and power in southern Italy. Their power was further depleted by the Romans and Samnites, who pushed them north of the Tiber, and finally by the Celts, who in the late fifth century broke Etruscan power in the north. Their final major defeat occurred when Rome took the nearby city of Veii in 396, ending their threat to the new power in central Italy.

The Etruscans were not a consolidated league like Rome and they were not like the independent city-states of Greece, so when Rome began its conquests in the fourth and third centuries against individual cities, the Etruscans could not mount a formidable defense, and Rome ultimately conquered the Etruscans in Etruria and absorbed them.

The Etruscans imparted to the Romans many of their religious attributes. For example, the Roman temples differed from Greek temples in that they had a frontal approach, with steps only ascending in the front, as opposed to the Greek style, with stairs all around. The cella (room) contained a cult statue in the back of the temple, which was approached from the front porch.

This frontal axis displayed an altar outside the temple, followed by stairs up and through a colonnade, with an inscription overhead naming the god or goddess, and then into the enclosed walled room in the rear. Like the Greek temples, the Roman temples were seen as houses for the gods when they visited and in which their offerings could be stored for later use. The Etruscans acted as a strong transmitter of Greek culture to the Romans before the fifth century.

Date added: 2024-08-19; views: 443;