Aerobic Exercise and Stress Reduction

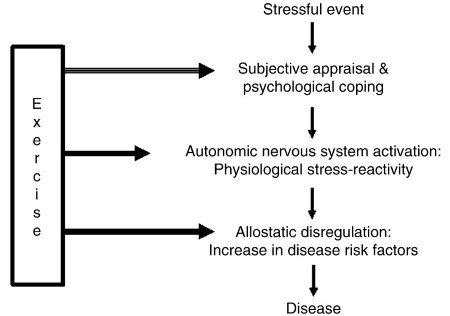

Sites of Interaction between Stress and Aerobic Exercise. This article reviews the evidence that regular aerobic exercise counters the detrimental effects of psychological stress. The hypothesized psychological, psychophysiological, and physiological effects of exercise are summarized in Figure 1. In order to protect against psychological stress and stress-related disease, exercise is hypothesized to have the following effects: (1) improve psychological coping with stress, (2) reduce physiological reactivity to stress, and (3) counteract the dysregulatory effects of stress reactivity on disease risk factors.

Figure 1. Hypothesized influences of aerobic exercise on the psychological and physiological effects of stressful events

Psychological Coping with Stress. Most of the research on the beneficial psychological effects of regular aerobic exercise has concentrated on improvements in well-being, often defined as the absence of negative affect, or on improvements in selfesteem and self-efficacy. Reducing negative affect, e.g., anxiety, hostility, or depression, decreases the chance that an event will be perceived as stressful (primary appraisal). Increasing feelings of self-efficacy increases the chance that coping skills are perceived to be adequate to deal with a stressful situation (secondary appraisal).

Well-being and self-esteem further modify interpersonal behavior such that less conflict is generated, and they favor adaptive problem-oriented coping and social support seeking over detrimental coping strategies such as denial and social isolation. Thus, exercise-induced improvements in psychological coping with stress may decrease the number of situations that are perceived to be stressful. This will decrease the frequency and duration of physiological stress reactions mediated by the autonomic nervous system. That is important because such stress reactivity, when often repeated, is thought to give rise to physiological dysregulation and ultimately disease (see Figure 1).

Regular exercisers have consistently been found to show the iceberg profile: they have higher vigor (the peak of the iceberg) and lower levels of anxiety, tension, apprehension, depression, and fatigue compared to nonexercisers. They are also found to be more outgoing, have greater self-esteem and selfefficacy, and score better on tests of coping skills. However, the coexistence of a healthy mind and a healthy body does not prove that the healthy mind is a consequence of the healthy body (such causality was never suggested by Juvenal, the Roman satirist who originated the adage of mens sana in corpore sano - he just prayed for both).

The beneficial psychological makeup of exercisers in cross-sectional studies may be based on common underlying influences on both exercise behavior and psychological distress. These may be of a genetic origin, or they may reflect environmental influences such as low socioeconomic status and poor social support networks that affect both exercise behavior and psychological well-being. Most importantly, the association may reflect a reversed causality, namely, that emotionally well-adjusted, agreeable, and self-confident individuals with low levels of stress are simply more attracted to sports and exercise, or that only such persons have the necessary energy and self-discipline to maintain an exercise regime. In short, the favorable psychological profile of exercisers may reflect self-selection.

To prove that exercise can be used as a prophylaxis against stress and stress-induced disease, longitudinal training studies are needed. Such training studies must be carefully designed. Subjective expectations, distraction, social attention/interaction, and trainer enthusiasm must be separated from the effects of aerobic exercise per se.

Therefore, the effectiveness of aerobic training must be compared to a placebo treatment, which may consist of stress management training, meditation, muscle relaxation, or a nonaerobic exercise program that aims to increase strength or flexibility rather than aerobic fitness. The subjects must not be allowed to choose these treatments, but are randomly assigned to either aerobic training or control treatment to prevent self-selection of subjects with a specific psychological makeup or a relatively high aerobic endowment into the training group.

Several well-designed longitudinal studies have reported improved mood or reductions in coping behavior, depression, and anxiety after a program of aerobic exercise training in comparison to control manipulations. Unfortunately, many others have failed to replicate these training effects. The most promising evidence comes from studies in clinically depressed patients. These studies tend to report beneficial psychological effects of exercise that match or even exceed those of pharmacological treatment.

Even in nonclinical populations, the training-induced changes in anxiety, depression, or self-esteem - when found - were generally largest in the subjects with the least favorable psychological profile before the start of the training. Without denying the potential of exercise as a therapy in subsets of subjects, most of the many reviews on this topic express only cautious optimism about the use of exercise for stress prevention in the population at large.

Date added: 2024-08-23; views: 458;