Psychophysiological Stress Reactivity

The various training-induced adaptations in the organization of the autonomic nervous system and its target organs, e.g., dominance of the parasympathetic over the sympathetic nervous system, greater sensitivity for hormonal cues (ß-adrenergic receptors, insulin sensitivity), and better vascularization of muscle tissue, may all critically influence the pattern and intensity of physiological responses to stress, even if psychological coping with stress is unchanged.

Although peak reactivity may not be influenced or even larger in exercisers, habituation during stress and recovery after stress may be faster, analogous with their physiological adaptation to bouts of exercise. An extensive set of studies has compared stress reactivity of well-trained exercisers with that of untrained nonexercisers. In about half of these studies, reduced stress reactivity and/or enhanced recovery was found in exercisers.

The reverse was found only twice. Although these studies support the idea of lower stress reactivity in exercisers, they were mostly cross-sectional in nature. Consequently, self-selection factors and differences in endowment for fitness and/or psychological makeup, rather than exercise behavior, may explain the differences in reactivity.

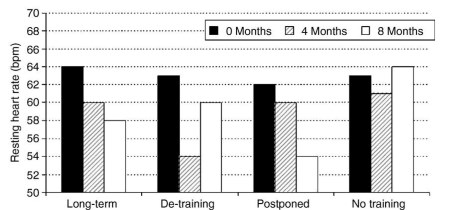

Again, training studies yield the most meaningful answers. Figure 2 provides an example of a typical design of a study to assess exercise training effects on physiological stress reactivity. In this study, four groups of adult males took part in an aerobic training program consisting of two to three sessions weekly over periods of either 4 or 8 months. Control subjects were put on a waiting list for 4 months or remained untrained entirely. Some of the trained subjects were de-trained; after an initial 4-month training program, they had to abstain from intensive exercise for 4 months.

Figure 2. A design for a training study (de Geus et al. (1993) Psychosomatic Medicine 55, 347–363) on physiological stress reactivity. The effects of the experimental manipulation are illustrated by the effects on resting heart rate

The figure illustrates how the various manipulations were closely followed by changes in resting heart rate. The effectiveness of aerobic training was further measured by the peak oxygen consumption during a supramaximal exercise test, expressed as milliliters oxygen consumed per kilogram body weight (VO2max). VO2max is generally held to be the best indicator of aerobic fitness and is highly correlated to actual endurance performance (e.g., Cooper test or shuttle run).

The average improvement in VO2max amounted to 14% after 4 months and 16% after 8 months, which is the gain usually attained in longterm and intensive training programs. In spite of improved fitness, this study found no evidence of an effect of aerobic exercise training on an extensive set of physiological responses that included heart rate and blood pressure, stress hormones, indices of cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic drive, and indices of peripheral vascular versus cardiac output responding.

Stress reactivity tended to decrease over repeated measurements, but the decreases in reactivity were not affected by aerobic training or ensuing de-training. These results correspond fully with those of many other studies showing that aerobic training does not systematically reduce reactivity to stress or enhance recovery afterward.

Date added: 2024-08-23; views: 411;