Exercise and Stress: Opposing Effects on Disease Risk Factors

A final interaction between stress and exercise can be found at the level of disease risk factors, where exercise may systematically oppose the physiological impact of repeated stress reactivity. Evidence for such an interaction comes from the field of cardiovascular disease. Chronic stress is thought to negatively influence a set of atherogenic factors such as high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (bad) cholesterol, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (good) cholesterol, high triglycerides, high insulin, high heart rate and blood pressure, and a disturbed balance in the coagulation and fibrinolysis of the blood.

This cluster of risk factors is a common clinical finding that is not constituted at random but is the multifaceted symptom of a basic abnormality, called insulin resistance syndrome, rooted in overweight and inefficiency of the (muscular) tissue to take up glucose. These risk factors affect the integrity of the arterial walls in synergy, such that stress-induced increases in levels in one of these parameters increase the pathogenic effect on all of the others.

A few hours of exercise per week is known to be able to counter all these detrimental effects. Although no effects on stress reactivity (task minus baseline) are found, virtually all training studies show a decrease in absolute levels of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure during baseline and stress conditions. This effect is completely reverted after de-training, which strongly argues for a causal effect of exercise.

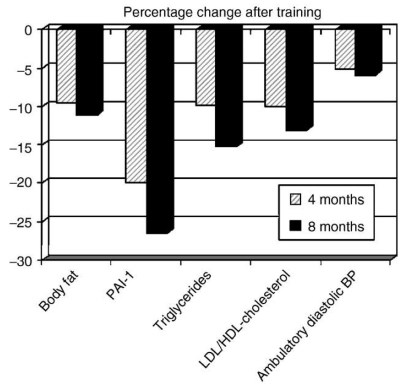

Ambulatory studies have confirmed that the significant decrease in heart rate and blood pressure remains intact in naturalistic situations. In addition, regular exercise reduces the LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio and triglyceride levels, increases fibrinolytic potential of the blood, and does so most likely through preventive maintenance of muscular insulin sensitivity. Figure 3 shows some of the simultaneous beneficial effects on various risk factors using data from the 4- and 8-month training programs described in Figure 2.

Figure 3. Beneficial effects of 4 and 8 months of aerobic exercising on a cluster of risk factors that are suspected to be affected by psychophysiological stress reactivity: percentage body fat; plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) activity, a risk indicator for disturbances in the coagulation–fibrinolysis balance; triglycerides; ratio of LDL (bad) to HDL (good) cholesterol; and ambulatory diastolic blood pressure

In conclusion, aerobic exercise should be seen as an excellent way to compensate for or prevent stress-related deterioration of cardiovascular health, even if psychological makeup or the acute reactivity to stress is unchanged after months of training. These health benefits suffice to strongly encourage the promotion of aerobic fitness programs to compensate for the aversive effects of daily stress.

Date added: 2024-08-23; views: 443;