Time in geology. Various theories

Most geologists of the first half of the nineteenth century accepted that the Earth must be very old. As far back as 1779 Georges Louis Lectere. Comte de Buffon (1707-88), had argued that 75 000 years must have elapsed since the Creation: in Russia Mikhail Vasilievich Lomonosov (1711 - 65) had proposed that the Earth must be hundreds of thousands of years old, in 1785 Hutton had hoped for time unlimited; and by the 1810s geologists were thinking of the age of the Earth in terms of millions of years.

To some extent this development was a result of diminished respect for the Scriptures and their chronology, but far more important in bringing about the change were two discoveries arising from stratigraphical studies. First, such studies had revealed the enormous total thickness of the world's sedimentary pile. In On the Origin of Species (1859), for instance, Charles Darwin (1809 - 82) quoted 13 3/4 miles (22 km) as the cumulative total of the British strati graphical column.

Clearly the formation of so great a thickness of sedimentary strata must have occupied an enormous length of tune. Second, within such sedimentary rocks an amazing variety of fossils, many of them representing now extinct tile forms, was discovered. Again, it seemed obvious that the development, existence and ultimate extinction of so many species must have occupied an eon of time.

Thus from the 1830s onwards geologists really felt few temporal constraints upon their speculations, although in the middle decades of the century the physicist Lord Kelvin (1824-1907) did cause some consternation in the geological camp when he employed physical arguments in an effort to restrict the age of the Earth to less than fifty million years. His reasoning was based upon the supposed rate of the Earth's cooling from its presumed origin as a gaseous ball, but his logic was later undermined by the discovery that the release of radioactive energy was constantly augmenting the Earth's heat balance. This left the geologists free to return to their belief in an enormously ancient Earth, and today » it is thought that the true age of the Earth must be around 4600 million years.

It was Sir Charles Lyell (1797-1875) who made the geological world fully aware of the possibilities inherent in the new. extended lime scale. The first volume of Ins classic Principles of Geology was published in London in 18 10. and achieved enormous popularity reaching its twelfth English edition in 1875. It was Lvell's object to demonstrate the validity of Hutton's thesis that slow-acting natural processes, such as those operating around us today are entirely adequate to explain all geological phenomena. provided sufficient time is allowed for their operation.

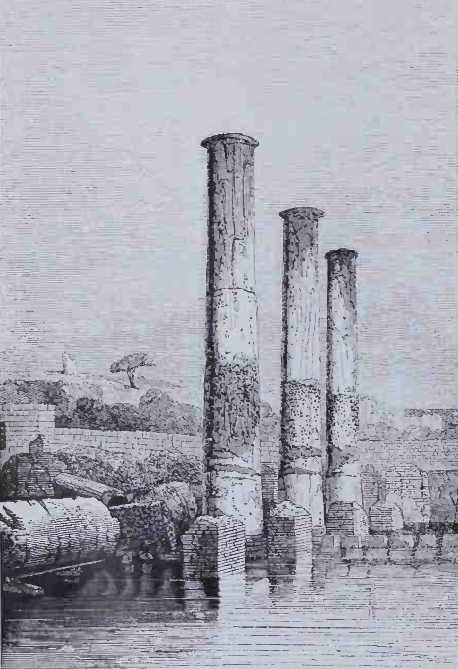

There was no need to invoke catastrophic events, no need even to suppose that present processes had operated with greater intensity in former years, in short, Lyell taught that the present is the key to the past - he became the foremost advocate of the uniformitarian philosophy. One site held particular significance for Lyell and was regularly illustrated in the Principles: the so-called Temple of Jupiter Serapis lying near Pozzuoli on the Bay of Naples (Figure 1.10).

1.10: The so-called Temple of Jupiter Serapis near Pozzuoli on the Bay of Naples. From Sir Charles Lyells Principles of Geology (seventh edition. London. 1847)

The temple is known to have stood above sea level in the second century ad, but the presence in the marble columns of marine bivalve borings up to a height of 7 m above high-water mark shows that at some time since the second century the temple has been submerged to at least that depth. It then rose again so that in Lyell's day the platform of the temple stood 300 mm below high-water mark. All this, Lyell observed, had happened as a result of Earth movements so gentle that some of the temple’s slender columns had survived without being toppled.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 719;