Nineteenth-century advances. The Huttonian theory

The Huttonian theory had suggested that Earth history consisted of an endless succession of interchanges of land and sea. This sequence of submergences and emergences was essentially unravelled by the nineteenth-century stratigraphers through their studies of the Earth’s strata, some formations being of terrestrial origin and others marine. But they were to discover that the story of the Earth was far more complex than Hutton could ever have supposed. In three areas — paleontology, paleoclimatology and tectonics — the unexpected complexities proved to be quite astonishing in their character.

Long before the nineteenth century it had been recognized that many fossils were representatives of now extinct species. It had even become clear that extinction was by no means a fate reserved exclusively for small creatures such as corals and molluscs; Pierre Simon Pallas (1741-1811), for instance, had in the 1770s described the remains of the extinct mammoth and woolly rhinoceros which are so widespread in the Russian Arctic. The geological world was nevertheless entirely unprepared for the discovery of the remains of the great Mesozoic reptiles — the dinosaurs.

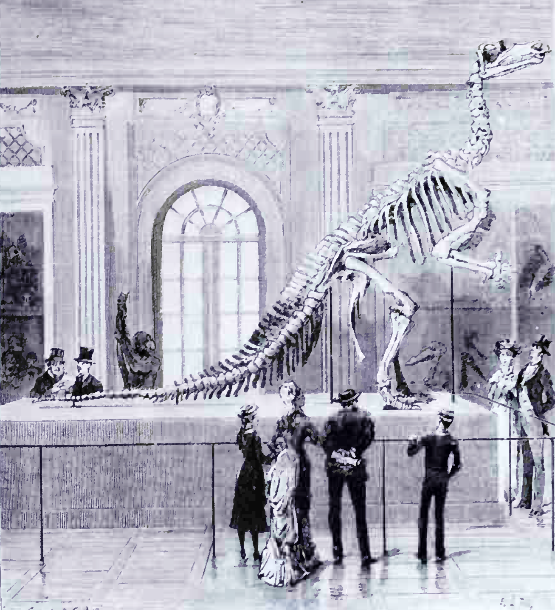

The first dinosaur fossils to be identified—they were parts of an iguanodon—were unearthed in the 1820s by Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790-1852) at Tilgate Forest in the Cretaceous rocks of the English Weald. Equally famous were the remains of the ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs retrieved by Mary Anning (1799-1847) from the Liassic clays at Lyme Regis on the south coast of England. By the middle of the century a wide range of massive Mesozoic creatures was known; they immediately captured the public interest and this they have ever since retained (Figure 1.11).

1.11: A giant ignanadon on show in the Brussels Museum. From Le Nature (Paris, 27 October 1883)

Many of the most remarkable nineteenth-century discoveries of extinct reptilian and other vertebrate life forms were made between the 1860s and the 1880s in the Mesozoic and Tertiary beds of the American West, ranging from New Mexico northwards into Wyoming. In that region a fierce rivalry developed between Edward Drinker Cope (1840-97) and Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-99), each man determined to disregard both natural hazards and the Indian menace in an effort to outdo the other in the unearthing of further and even stranger new species. It was these paleontological discoveries, the outlandish and the commonplace, which provided the vital historical underpinning for that most famed of nineteenth-century scientific theories — Darwin’s theory of the origin of species by means of natural selection.

Geology revealed that dramatic changes had occurred in the Earth’s flora and fauna, and remarkable fluctuations in the Earth’s climates were also discovered. In particular it became clear that recently there » had been a glacial period during which large portions of the Earth’s surface had been shrouded by ice sheets such as those that today survive only in Antarctica and Greenland.

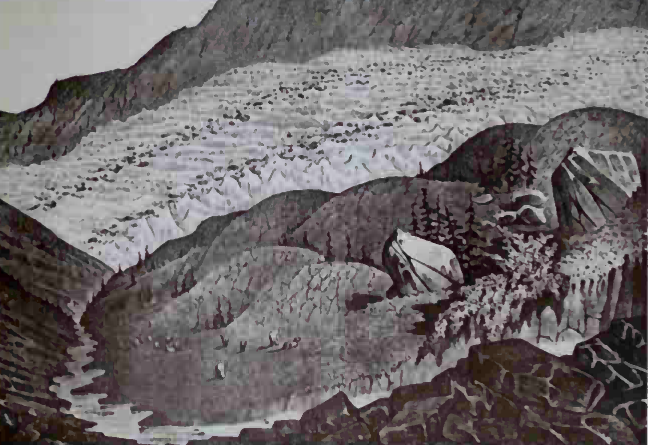

The glacial theory began to be developed during the 1820s in Switzerland following the realization that erratics, moraines, striations and other phenomena lying downstream of the snouts of the present glaciers could most conveniently be explained by supposing those glaciers once to have been more extensive than they are today. In 18)6 the idea was taken up by Louis John Rodolph Agassiz (1807-73) and in the following year he began to use the term the Ice Age (die Eiszeit) and to voice the somewhat exaggerated view Chat the whole of Europe as far south as the Mediterranean had recently been engulfed by ice flowing southwards from the North Pole (Figure 1.12).

1.12: Clacialli polished rocks and moraim debris at the edge of the Zerman glacier. From Louis Agassiz's Etudes sur les glaciers ( 1840)

To many, this idea of a glacial 'deluge' seemed dangerously like a reversion to Catastrophism, particularly since there seemed to be no mechanism available to account for the supposed refrigeration. But gradually, during the l840s and 1850s, it became increasingly clear that the ice of former glaciers did offer the best explanation for the vast spreads of sand and gravel mantling so much of the northern hemisphere Indeed, it was soon perceived that the Pleistocene glaciation was but the most recent of a number of such events; it was in 1856 that William Thomas Blanford (1832 - 1905) ascribed a glacial origin to the Talehir conglomerates of India, thus taking a first step towards the recognition of the widespread Permo- Carboniferous glaciation of lands that were once located in the southern hemisphere.

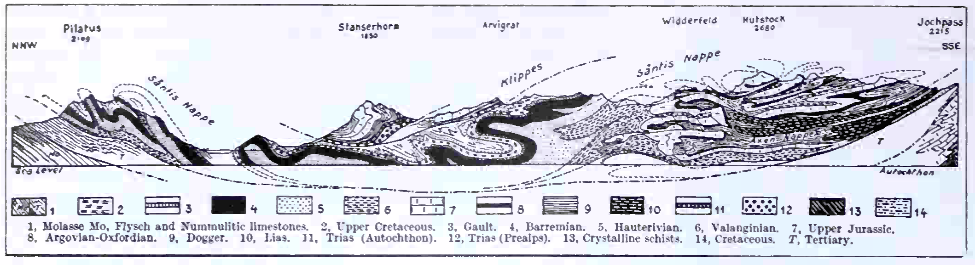

The third of the three startling discoveries was that our continental rocks have been subjected to tectonic movements upon a gigantic scale. In some places vast slices of rock were found to have been forced over their neighbours for distances of tens of kilometres, while in other places detailed mapping of the rocks showed them to have been bent into huge recumbent folds or nappes. It was in 1841 that Arnold Escher von der Linth (1807-72) first described such structures in the Alps, and his work there was later developed by Albert Heim (1849-1937) (Figure 1.13).

1.13: A section across the High Calcareous Alps of central Switzerland compiled by Albert Heim. From Leon William Collet’s The Structure of the Alps London, 1927)

In the 1880s Lapworth identified similar structures in the north-west Highlands of Scotland where large-scale movement has occurred along the Moine thrust. Looking at the cross-sections of the region arising from his field studies. Lapworth remarked: 'Such sections are to a certain extent astounding, yet they do occur His amazement is understandable, but such overthrusts are now known to be a commonplace phenomenon.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw the Earth sciences take rapid strides forward: the second half of the century was a period of consolidation. One sign of the increasing maturity of the Earth sciences in the years after 1850 was the establishment of specialist societies such as the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1876) or the Seismological Society of Japan (1880). Geologists were also feeling the need for closer international cooperation, and. following an American initiative, the international Union of Geological Sciences was founded. Its first meeting was held in Paris in 1878. since when the Union has reconvened every few years in cities the world over.

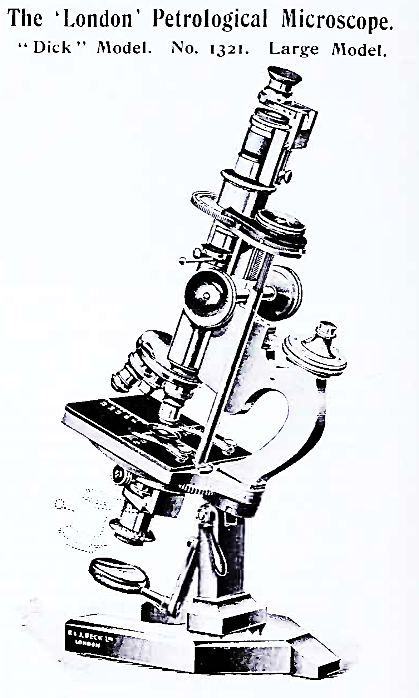

One of the most significant developments in the Earth sciences during the second half of the nineteenth century was the development of a new and vitally important technique: the examination of rocks in thin section using the petrological microscope. Its originator was William Nicol (c 1768 – 1851) of Edinburgh. Anxious to study the microstructures in fossil woods, in about 1830 he ground down some wood specimens until they were transparent enough to be studied beneath a microscope. Initially there was little interest in his idea, but in the 1850s Henry Clifton Sorby (1826 - 1908) learned of Nicol's technique and applied it to the production of thin sections of actual rocks. Again geologists were slow in appreciating the full significance of the work- some thought it absurd to study the structure of a mountain through a microscope — but in the 1870s the achievements of Nicol and Sorby at last made their impact when Ferdinand Zirkel (1838 - 1912) in Leipzig adopted the new technique enthusiastically. From that time onwards the rock in thin section and the petrological microscope have been two of geologists' most valued aids (Figure 1.14).

1.14: An early petrological microscope. From a catalogue of scientific instruments issued by R. & J. Beck Ltd (London, c 1910)

One other development of the second half of the nineteenth century deserves mention because, although trivial in itself, it held enormous portents for the future. In 1859 at Titusville, Pennsylvania, в the Drake well, the world's first oil well, was drilled. Until then geologists had thought about neither the nature of oil and natural gas nor the possibility of large-scale exploitation of the world's oil resources. This was soon to change, for from that small beginning in 1859 has grown the enormous modern oil- and gas-producing industries, in which geology and geologists have played a vital role.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 677;