Memorials and tombs of martyrs. Story. Continuation

Other tombs jostle one another on all sides, and, as at Bonn, an enclosure for Christian burials seems to have taken the place of an even more haphazard series of pagan interments. At a number of other places, in eastern France as well as in the Rhineland, clear evidence has been found of venerated burial-places, such as those of St Severinus at Cologne, Irenaeus at Lyon or the local saints of Metz and Mainz, lying beneath churches often of much later construction.

The precinct, open to the sky, transformed by stages into a martyr-church of great magnificence: such seems to have been the usual course of development. A modest example may be traced at Tipasa, on the coast of Algeria. The site seems to have been at first a simple burial-ground, enclosed by a wall and connected with a subterranean grotto. In about the year 400 Bishop Alexander converted the precinct into a chapel, its pillars irregularly ranged within a building that is five-sided rather than rectangular because one wall is awkwardly re-aligned to include the entrance to the grotto.

Many tombs and at least one semicircular table for use at funeral feasts were dotted about the floor, while two parts of the chapel were set aside for special purposes. An apse at the west end contained a single tomb, perhaps that of the founder bishop, while a group of revered tombs was gathered together and packed closely one against the other to form the floor of a sanctuary beneath and just behind the raised altar. The men thus honoured are described in an inscription as 'the righteous of an earlier time', an expression which may mean that they were martyrs but might also refer simply to Alexander's predecessors as bishops of Tipasa. In either case this church illustrates the fashion whereby the tombs of saintly persons, grouped in the open air during a period of persecution, were subsequently protected by a shrine both from the elements and from undue pressure by less worthy persons.

Something of the same kind occurred at Nola, near Naples. Here the wealthy bishop Paulinus modified and in large measure rebuilt the church at the beginning of the fifth century. His particular interest was the tomb of St Felix, which he enclosed in a courtyard skirted by low walls pierced with arches on supporting columns. This courtyard formed a graceful portico set in front of the new church, a rather splendid basilica with trefoil choir.25 Walls, columns and paved floor were of marble while the roofs of mosaic shone in the light of numerous lamps suspended from the ceiling.

But attached to the church was a complex of rooms, some of which, modest in dimension and with no claim whatever to artistic excellence, were no more than rectangular halls set up at an earlier period to protect such martyr-relics as had been gathered together for the edification of the faithful. Not only were these first halls of an unpretentious type, but the tombs made no claim to distinction and were quietly covered, without any feeling that their virtue was thus extinguished, by the flooring of stone slabs and mosaic which Paulinus provided. The curious effect of the constructions at Nola is that, although the great St Felix lay in an honoured tomb, this tomb remained outside in a shrine of its own. At Nola, as at Bonn and Xanten, martyrs might be revered piously yet with an entire absence of display.

Antioch, in Syria, provides several examples of collective martyr-shrines. There is, in the first place, the Cemetery, a precinct within which lay the bodies of numerous martyrs who had met their deaths in a series of persecutions. Some enjoyed the dignity of a chapel assigned to their own particular cult, but many were packed closely together with the tombs of the faithful crowding about them. There is the 'Martyr- shrine of the Romanesian Gate', where the bodies of a number of saints were deposited, with what might seem a certain lack of ceremony, in a low crypt underneath the pavement of the sanctuary. The coffins lay on the ground and could be moved about in any emergency, so that, when the crypt became a place of interment for Arian heretics during the latter years of the fourth century, the coffins of the orthodox were transferred to an uncontaminated resting-place in the upper part of the church.

The development of the martyr-shrine is illustrated best of all by the excavations which have been carried out at Salona, a military base on the Dalmatian coast where the emperor Diocletian, a native of the place, built himself a vast palace rather on the lines of an elaborate army camp. Naturally there was no lack of buildings appropriated to the various cults of the Empire, and these served to suggest the form taken by the shrines dedicated to the Christian martyrs. Pagan chapels could indeed be taken over with little adaptation for Christian uses.

One instance of this is offered by the chapels sacred to Nemesis, the goddess of Fate, which were part of the equipment of the amphitheatre at Salona. These chapels were situated close by the passage along which the gladiators passed into the arena and along which, in the time of Diocletian's persecution, the company of Christian martyrs advanced to meet their death. After the victory of the Church, oratories where the gladiators had made their vows to Fate became memorial chapels to the martyrs who were commemorated, before the end of the fifth century, by inscribed pictures which adorned the walls.

Salona fell completely into decay after its sack by the Avars in the year 614. The pattern of Christian life has therefore to be reconstructed from fragmentary remains, but three principal cemeteries may be distinguished where churches took their form under the influence of martyrs' tombs and the holiness attributed to them.

At one of these cemeteries, Kapljuc, the church, constructed bv Bishop Leontius about 360 ad, is shaped as a basilica. The plan is commonplace enough, composed of a nave from which aisles are marked off on each side by a row of columns, an apse, and, at the opposite end of the building, an area largely taken up by tombs and memorials. But it looks as though the basilica of Leontius represents the final stage in a process of development extending over half a century. Originally the apse was set up against a piece of wall to shelter the body of the martyred priest Asterius, in accordance with an earlier practice, illustrated by frescoes at Pompeii, whereby semicircular walls, occasionally amplified into the form of a vaulted apse, served to protect a votive column or funeral monument.

The saint's devotees gathered in the open air, but there was not a great deal of room and only a little way off stood another celebrated martvr- tomb which took a rather different form. This was the sepulchre of four military saints who, like Asterius, had met their deaths in Diocletian's persecution, and the upper surface of the tomb, with holes for the pouring of libations, provided a convenient table at which the faithful might celebrate their feasts of commemoration; for this purpose a bench also was supplied. These two rather primitive martyr-shrines were subsequently linked together, in that they were enclosed by a rectangular precinct isolating them from more ordinary graves.

The third stage was reached when Bishop Leontius, regarding as inadequate an arrangement which left the worshippers standing in the open air, constructed his basilica which, without disturbing the precinct that contained honoured tombs, should simply include it within the space of an ample chancel. Around this a miscellaneous array of tombs and mausolea sprang up, clustering as close as possible to the shrines of the 'holy martyrs whose ashes drive far away the wicked demons'.

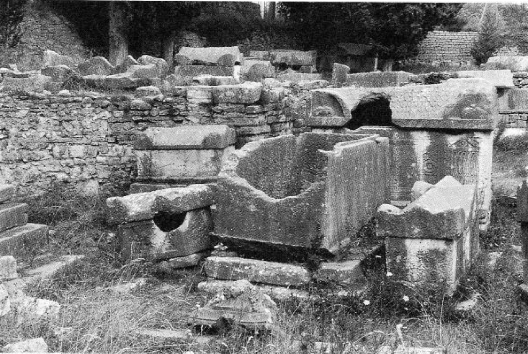

The Manastirine cemetery at Salona had a history not unlike that of Kapljuc. The nucleus seems to have been a martvr-tomb, probably that of Bishop Domnio, attached to the wall of a villa and sheltered by an apsidal canopy. Around this the faithful thought it fitting to construct a precinct shaped with a fairly wide cross piece and a rather narrow approach section: in other words it resembled a church lacking aisles but with the rough equivalent of a transept. The picture is complicated by the large number of competing shrines which jostled up against that of Bishop Domnio, and when the church was extended lengthways to form a basilica of more regular shape, the whole area near the martyr's grave was cluttered with the chaotic jumble of tombs discovered when excavations were carried out at the end of the nineteenth century (fig. 54).

54. Salona, Manastirine cemetery: coffins jostling the tomb of Domnio

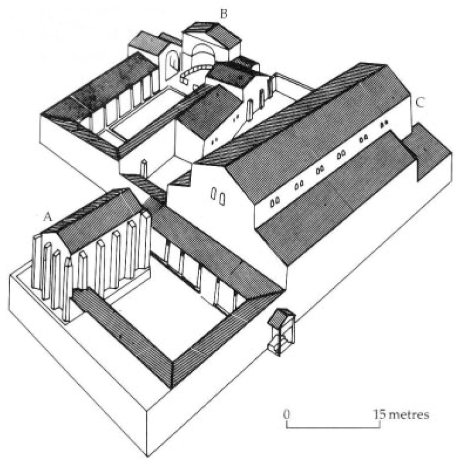

The Marusinac cemetery, also at Salona, tells a similar story (fig. 55), though here the area was apparently in private hands and development followed a somewhat more leisurely course. Here again the focal point was a tomb, that of the martyr St Anastasius, a fuller who was thrown into the sea by order of Diocletian. Apparently the body of Anastasius was first laid in a chapel constructed by a wealthy woman named Asclepia.

55. Salona: reconstruction of Marusinac cemetery. A. Original shrine; B. Second shrine; C. Roofed basilica

This chapel, a buttressed rectangle with small, internal apse, was arranged on two floors. The altar of remembrance was perhaps set on the upper floor immediately above the martyr's grave while, more certainly, places were reserved at the lower level for the tombs of Asclepia and her husband. This somewhat restricted arrangement did not last very long, and the body of Anastasius was removed to a vaulted apse, easier of access, nearby. Two matching rectangular rooms were built north and south, making a transept in rudimentary form.

The central space was left open to the sky so that when, as at Manastirine, the funeral complex was enlarged, the appearance inside was that of a courtyard set in front of a sanctuary and flanked by covered enclosures. The general shape, again, is that of a basilica but one with a roofless nave. The colonnaded portico of this church extended to meet another church of St Anastasius, a roofed basilica of conventional pattern built with considerable splendour as indicated by the well-preserved mosaic of geometrical patterns which adorns the floor. The shrine of Marusinac therefore came to possess two churches set very close together and nearly parallel.

Though now in a sadly ruined state, the cemeteries at Salona serve to demonstrate how the cult of the martyrs, adopting some of the practices and architectural forms of pagan hero-worship, influenced, at any rate in detail, the development of Christian churches.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 859;