Memorials and Martyr-Shrines. History

The strange notion of placing two churches side by side, which is what a double basilica amounts to, may perhaps be explained in terms of a difference of function. For, in addition to the churches required for straightforward congregational worship, another type of building found favour as a place where commemoration might be made of the departed and, in particular, of the martyrs. Here also Christian practice had been influenced by the customs of the pagan world.

In Rome offerings and banquets in honour of the departed, particularly on the ninth day after a death, were a part of pious family practice, while the festival of Parentalia, in February, served as a kind of All Souls' tide when such celebrations were the general rule. During that week the temples were closed and magistrates appeared without their badges of office; it was a time of solemn commemoration when living and dead might seem to feast together in clannish solidarity. Sometimes a tube was forced down into the vessel containing the ashes of the dead in order that these might literally have their share of the wine which the rest of the family were enjoying above.

In Christian circles the commemorative rites were of two kinds: the offering of the Eucharist, 'medicine of immortality', and the gathering together of family and friends for a community supper. But the two are not always clearly distinguished in the accounts and sometimes Eucharist and supper were combined, the one following the other. It was laid down, certainly by the fourth century, that the third, ninth and thirtieth days after a death in the family were fitting times for ceremonial observance, though the funeral suppers on occasion diverged from being the 'perfectly sober feasts' which Constantine approved into occasions of luxury and even licence which bishops felt obliged to curtail.

The desire therefore arose for buildings other than the churches designed for everyday use, where proper respect might be paid to the departed and, in particular, where the martyrs could be honoured. The Greek poet Hesiod had described the men of the Golden Age as 'kindly, deliverers from harm and guardians of mortal men', and similar virtues and powers were assigned, in Christian practice, to the martyrs. Theodoret, a scholarly Syrian bishop, explains the tradition of the Church by adopting Hesiod's lines and commenting on them in this way:

Now we, in similar fashion, acclaim as 'deliverers from harm and healers' those who were distinguished for devotion and met their death on that account. We do not call them 'divine'—may such mad folly be ever far from us!—but we speak of them as friends and servants of God who use their free access to him for the kindly purpose of securing for us an abundance of good things.

The value thus attached to the effective virtue of the martyrs led to a keen desire for burial as close as possible to a martyr's tomb, and funeral inscriptions bear witness to the belief that, when the day of Resurrection arrived, the martyrs, as they rose to life eternal, would draw along with them those whose bodies lay nearby. The earliest shrines, usually discovered only by excavation beneath two or three stages of later building, lack adornment or distinction of any kind but are tight packed with a disorderly lumber of coffins.

This clustering of tombs continued, at least in the West, when, in spite of Roman law, which declared that tombs should be inviolate, relics of the martyrs were transported from place to place and set in or close to the altars. St John, in his Revelation, 'saw underneath the altar the souls of them that had been slain for the word of God', and the original fixture, around which the martyr-shrine and, later, the martyr-church developed was the altar-slab adapted for funeral feasts.

Sometimes the first thing necessary was to clear space around the tomb in order to allow free access for the faithful. The Via Tiburtina in Rome, for example, was flanked with mausolea and tombs of every sort to which the Christian catacombs below ground provided a counterpart. One of these complex networks acquired high renown as containing the body of the martyred St Laurence. When peace was restored to the Church, the number of pilgrims increased greatly and Constantine, in an attempt to prevent ungracious jostling, isolated the tomb from its surroundings and hollowed out in the tufa a precinct22 of ample size, equipped with silver railings and much other decoration. It became customary for the pilgrims to assemble here, gaze at the tomb through a grating and let down strips of cloth which were then valued as bearing some touch of the martyr's healing power.

A few years later Constantine constructed another church close to and parallel with the original structure. This, the so-called basilica maior, eventually fell out of fashion and was allowed to collapse. Even its whereabouts were forgotten until excavation during the period 1950-7 disclosed the foundations. It proves to have been a large building, 95 metres in length, consisting of nave and two substantial aisles sweeping round and enclosing the apse. This style of building, which became a standard type in the fourth century, had two advantages in addition to its dignified appearance. Firstly, the break in the roof surface allowed the craftsmen to work with timbers of moderate size; secondly, as the aisles were lower than the nave, it was possible to insert clerestory windows all round and thus improve the lighting.

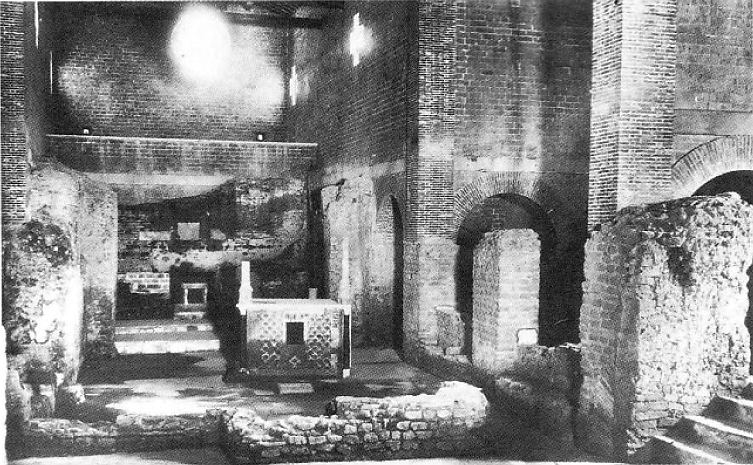

Even before the Peace of the Church some attempt had been made to ensure that the faithful might share in the liturgy celebrated on a martyr's anniversary. The underground chapel of St Alexander, on the Via Nomentana, shows the nature of these efforts (fig. 53). At first the bodies of Alexander and his companion Eventius lay in tombs that were difficult of access and the need therefore arose to construct nearby a triclia—the word originally means a bower or summerhouse—where a modest number of people might congregate for the services.

53. Rome: underground chapel of St Alexander

This triclia was still separated from the tombs by a partition-wall, so that the next stage was to excavate further and include the tombs within a more ample cult room which was enlarged a second time by breaking through some of the adjacent corridors. An altar-slab was set directly over the double tomb and enclosed by marble-lined panels with a grating (fenestella) in front which gave access to the relics below, while small columns rose from the four corners to support a canopy of honour. As Zeno, bishop of Verona, put it, the Sacrifice took place within 'sepulchres turned into temples' on 'tombs converted into altars'.

Development of a similar type occurred when the martyr's body lay not in a catacomb but in an open-air cemetery. Examples are provided by two cities that were military outposts of Empire in Lower Germany, Bonn and Xanten. At Bonn, excavations indicate arrangements of the simplest nature. The original shape of the cemetery was an informal, walled enclosure, pagan in character and containing two stone cubes which served as small tables for funeral banquets. One of the cubes still retains an earthenware vessel, let into its upper surface, designed to receive offerings of food and wine.

The cemetery appears to have passed into Christian hands about the year 300 and to have been enlarged at that time to provide space for numerous burials clustered around four sarcophagi which contained the bones of the soldier-martyrs Cassius, Florentius and their companions. The higgledy-piggledy layout was naturally felt inappropriate after a few years, and a paved meeting hall was built. Pagan tombstones were freely incorporated in the structure but crosses and the chi- rho emblem on the pavement marked it as a holy place where ever more imposing edifices might arise with the passing of the years.

Comparable arrangements have been noted at Xanten. Here too excavations carried out quite recently under successive layers of St Victor's church revealed a rectangular cavity enclosing two skeletons of men about forty years of age who had died as the result of repeated blows on head and chest. The skeletons have been identified, not unreasonably, with the local martyrs Victor and Mallosus. Whether that be so or not, there is certainly a funeral-table, roughly carved to receive offerings or to serve as an altar when the Eucharist came to be celebrated.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 803;