Exemplars for a Music Composition Pedagogy

What follows are brief overviews of selected literature that may help teachers at all levels of instruction build a composition pedagogy that is carefully crafted and richly designed in terms of philosophy and learning theory. Exemplars are organized in two sections: one devoted to larger conceptual frames and the other to more detailed examples of application. They are carefully chosen for their compelling meaning for today’s teaching environment and usefulness in expanding time devoted to creative activities— particularly music composition.

Conceptual Frame Exemplars.Five groups of writing are considered: (1) an historical account of music composition pedagogy, (2) two works that address philosophy/learning theory as a base for music composition, (3) writings on creativity broadly viewed in the psychology literature, (4) writings on creativity specifically relevant to music education and composition teaching, and (5) teacher/composers’ own powerful words and actions.

Composition Pedagogy: An Historical Account. In the opening pages of one of the only extensive studies of music composition pedagogy, Williams (2010) proposed that

a pedagogy of musical composition be adopted that would reunite technique and creativity in a common field of study. Modifications to the pedagogical approach toward the teaching of both Music Theory and Composition are proposed in order to ensure that neither pursuit would remain isolated from its interrelated counterpart. By combining the “details, methods or skills which are applied to [music composition]” with the “capacity for, or state of, bringing [music] into being” a pedagogy emerges that can address all aspects of learning to compose. [italics and quotation marks in original, pp. 2-3]

This notion of technical understanding joined with creative composition process is at the heart of many accounts of music composition pedagogy as it relates to western art music and can be found in modern accounts of composition pedagogy in popular music as well (Clauhs, Powell, & Clements, 2020).

The study by Williams (2010) provided an historical account of the growth of composition as an improvisational experience before the eighteenth century and based on the study of conventions in treatises such as those noted, by Zarlino and others (pp. 24-25). This tradition continued into the eighteenth century and became more codified by the emergence of rules of species counterpoint by Fux, the notion of thoroughbass, and the systematic study of harmony by Rameau. This would dominate studies of music in the nineteenth century (Williams, 2010, p. 39). Also of note were composers’ attention to melody as noted by the writings of Mattheson and the memorization of the “stock melodic schemata for the realization of thoroughbass, or partimenti, in a stylistically appropriate manner” (p. 44).

Amidst this historical/technical background in the development of what might be thought of as today’s field of music theory, came the nineteenth century conservatoire that established music theory as the important landmark of music instruction as it exists today. The beginnings of pedagogy for music composition were likely embedded into the instruction of music theory. Attention to the emergence of the great composers of western art music in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was often attributed to the mastery of historically defined technical skills together with the romantic “mystery of genius” attribution. This “mystery of genius” is one of the major “myths” that has been inaccurately used to explain creative achievement (Sawyer, 2012).

As time passed, it became clear that the mastery of technique and the “genius” notion were not enough to explain compositional achievement. “The idea that studies in Fuxian counterpoint and Harmony could—or at least should—no longer serve as preludes to studies in composition led to a divide between the fields of music theory and composition at the turn of the twentieth century” (Williams, 2010, p. 56). By mid-century the separation of music theory and composition was complete as schools of music established both closely related but separate courses of study, especially at the graduate level.

Williams (2010) ended his work with an analysis of selected books on music composition designed for higher education, noting strengths and weaknesses with an eye toward the balance of technique and creativity.4 Williams also noted that the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) guidelines for undergraduate and graduate programs in composition are purposefully vague and are of no help in understanding contemporary composition pedagogy. In fact, even to this day, the lines between music theory and composition may not always be clear.

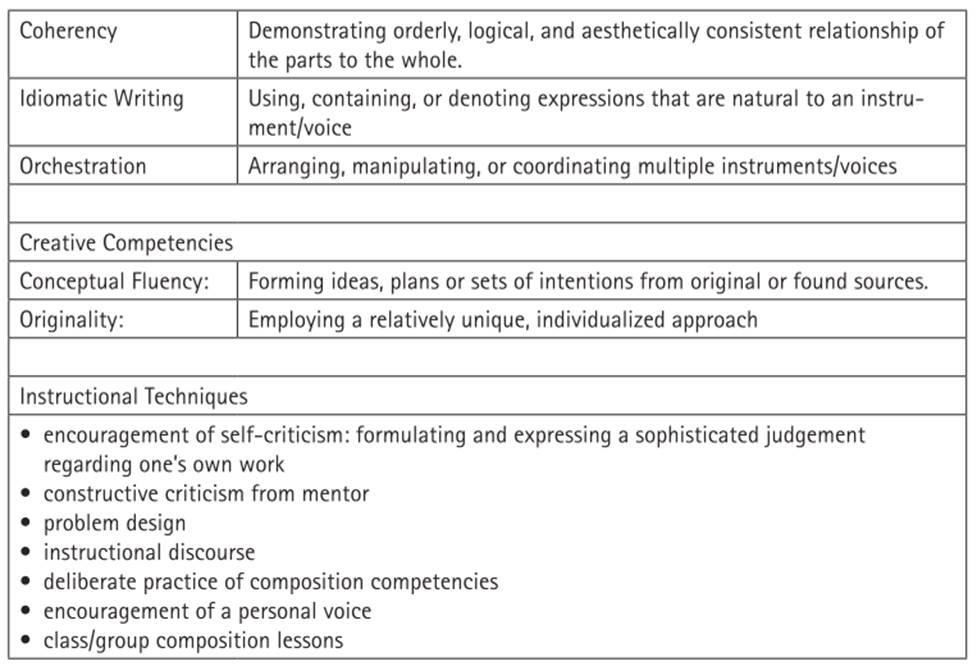

Perhaps to improve this, Williams proposed competencies that might be considered when framing music composition pedagogy, as well as providing hints toward some instructional techniques for guidance. These are displayed in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Technical/creative competencies and instructional techniques for music composition Pedagogy (adapted from Williams, 2010, pp. 107– 143)

Although crafted as recommendations for collegiate instruction, these competencies and techniques may be useful for compositional pedagogy at any level and appear in various forms in other exemplars to follow.

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 263;