Facilitating Engaged Music Listening

Thus far, we have considered ways in which music listening can serve as the foundation and inspiration for students generating compositional products. Student composers internalize models of pitch and rhythm patterns, harmonic and formal structures, and style-specific idiomatic features simply by listening to musics in their surrounding environments, with or without teacher guidance. Focused listening, however, can facilitate student composers gaining insight into the artistic music elemental relationships that lead to feelingful responses. As music educators, we have the opportunity to scaffold music listening experiences that deliberately draw students’ attention to ways in which composers organize sounds and create artistic and feelingful impressions.

What then are examples of specific pedagogical strategies that teachers might implement in order to lead students toward personal soundscape development and expansion, such that music listening directly leads to informed, inspired, and thoughtful compositions that are not only musically and artistically formed but are also emotionally engaging? How might teachers facilitate engaged music listening?

Much of my pedagogical and research work has focused on observing and analyzing students’ verbal, visual, and kinesthetic responses to music listening as means for driving student-centered pedagogy that facilitates music listening skill development (Kerchner, 1996, 2000, 2009). By considering what I have learned from music student learners, I offer the following pedagogical strategies as starting points for teachers to consider and adapt according to their specific music teaching and learning contexts.

Questioning and Offering Feedback. It can be challenging for teachers, who are typically highly trained and knowledgeable musicians, to remember that what they perceive and process musically is not necessarily what students recognize as obvious features of a music listening example. Similarly, what draws students into a music listening example may be completely different from teachers’ aesthetic and musical values developed throughout their accumulated (and presumably varied) music listening experiences. Therefore, it is important to select musical examples that clearly demonstrate a musical element, compositional tool, or emotional impression and to guide the music listening experiences for the purposes of engaged instructional listening. Students’ compositions might also serve as illustrative examples. While students listen to musical examples in order to inform their own compositional work, they can also learn from listening to, analyzing, and reflecting on their own work.

To add awareness to the music listening experience, teachers are encouraged to provide students with focus directives or questions that lead them to discover something specific in music listening examples—a pattern, a rhythm, an instrumental or vocal interaction, a theme, a melodic contour, or a feeling impression. Students bring these options into their own awareness as possibilities for their own compositions. Otherwise, teachers can assume that individual students will each focus their attention on a variety of musical features during classroom or ensemble music listening experiences. Both directives and questions are presented prior to the listening and serve to focus students’ attention. Debriefing about what the students noticed relative to the point of guided focus immediately follows listening to the musical example. These discussions, in turn, lead to another listening of the same musical excerpt to either listen for a different musical feature or to listen again for the original musical feature brought to the students’ attention, but perhaps missed in the plethora of musical information that moves rapidly through time and space.

A focus directive is a statement with which the teacher invites students to do something during the music listening, often as a way of gauging their listening discrimination skills. Sample directives include: “When you hear this theme (students learn to sing the theme before the question is posed), stand up" “Raise your hand when you hear the music begin to move faster (accelerate)" “Hold up your pointer finger when you hear the trombone, and hold up your pinky finger when you hear the flute" “As you listen to the music, think about how the composer created the image of a fast machine as we listen to John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine" The teacher gives the students a direction regarding what they should do or consider as they listen to the music. No question is actually posed, however.

Teachers’ carefully-worded focus questions posed prior to musical listening experiences can encourage students to imagine, think in musical sound, dream, predict, compare, contrast, anticipate, speculate, critique, reflect, and pose their own questions (Kerchner, 2014). A focus question is a prompt for the students to consider during the act of music listening. For example, “As we listen, which instruments do you hear? We’ll discuss after the music ends" Notice this particular focus question asks a “closed question" and converges on a correct response, usually offered verbally by students.

Another type of question is a “guided question" that points the students’ focus of attention toward something specific about the music. An example might be: “As we listen to the music, what do you notice about the way the different instruments play the theme when it returns in the conclusion of the composition?" This question focuses the students’ attention on the musical instruments and a repeated musical theme, but there is also room for students’ personal interpretations about the relationship between the instruments and the theme. Teachers pose “open-ended focus questions" prior to listening to a musical excerpt in order to intentionally prime cognitive and emotional wells. These questions solicit a variety of diverse student responses, certainly not limited to a single accurate response. Open-ended questions can also be crafted to be intentionally vague when teachers want to engage students’ imaginations and cast the net wide to see what they are thinking, feeling, and hearing as they listen to a composition. These open-ended questions might include: “What did you notice about the musical mood?" or “What did you notice or experience as you listened to this piece?"

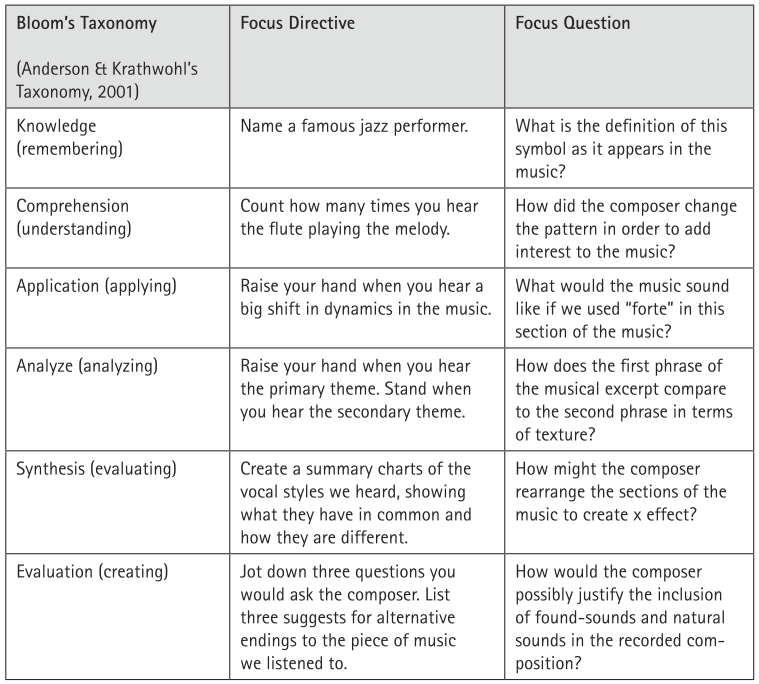

Providing focus directives and posing focus questions require teachers to reflect on what specifically they want the students to glean from the music listening excerpt. In addition to asking an array of questions—closed, guided, and open-ended—teachers are also encouraged to pose questions that engage the cognitive skills reflected in each of the six levels of Benjamin Bloom’s et al. (1956) Cognitive Taxonomy. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) reimagined this taxonomy by reversing the synthesis and evaluation levels within the taxonomy and using verbs (instead of nouns) to depict the how humans demonstrate the various levels of thinking.

Bloom’s hierarchical levels include foundational, concrete levels of thinking (knowledge, comprehension, and application) and move to the levels that represent higher- order thinking (analysis, synthesis, and evaluation). Asking questions that engage the type of thinking indicative of each level of the taxonomy helps students become cognitively flexible. Varied questioning moves students beyond lower-level memorization and recall of facts and into higher-level application and analysis. Developing these higher-order thinking skills results in the capacity to generate ideas, problem-solve, reflect, and develop personal preferences. Examples of questions and directives for each of Bloom’s taxonomic levels are found in Figure 10.1; Anderson and Krathwohl’s taxonomic descriptors are in parentheses.

Figure 10.1. Focus directives and questions based on Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956)

Teachers are encouraged to model how to articulate guided and open-ended questions and how to provide specific observational feedback on students’ compositional processes and products. Observational feedback statements (“I noticed that ….”) are especially useful to student composers, since they remove personal judgement and state directly what the peers (and teachers) have heard and experienced by listening to the composition. Peer comments such as, “This composition is good” or “I like it” provide the composer little detail for improving or taking alternative pathways toward crafting intended musical, artistic, or feelingful impressions. Instead, teachers might prompt peer reviewers to add the word “because” to complete the statement with description: “This composition is good, because….” Or “I like this composition, because….” With these observational and descriptive statements, student composers receive specific feedback, and peer reviewers develop their critical thinking skills by articulating the reasons for the feedback they offer the composer

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 264;