Victorian Fashion: Bustle Revival, Tailored Styles & Home Sewing

The tightly encased silhouette from the mid-1870s and early 1880s gave way to the second bustle phase from around 1882. Household Words magazine in 1881 reported that ‘Indications strongly favour a general return to the tournure’, heralding the arrival of a new bustle style, which was worn slightly lower than its predecessor and protruded at a sharper angle, giving a more ‘shelf’-like appearance to the back of the fashionable shape.

Overskirts developed interesting drapery effects, some of which could be asymmetrical and very complex. Cassell’s Family Magazine described this style in 1888, claiming ‘Some of best tailors are bringing in petticoats of contrasting colour, richly trimmed, over which a long upper skirt is draped, low on one side, high on the other’. Jacket bodices took on a tailored look, a style which grew in popularity in the next few decades.

Some had false waistcoat fronts with contrasting fabrics, and featured turned-back revers and rows of numerous close-set buttons. Sleeves were generally quite tight, sometimes with cuffs that matched one of the contrasting fabrics used in the central bodice section or turned-back revers. By the late 1880s a small gathered puff developed at the shoulder, which would eventually grow to large proportions in the 1890s.

Interestingly, like other times of big fashion change, there was a fear that the crinoline would once again come back into fashion. After a report that this was imminent, a contributor to The Girl’s Own Paper assured its readers in 1883 that ‘I am glad to say that no danger exists of the kind, for the principles of good taste are far too widely spread for any of the leaders in our English society to go far beyond what is now worn’. By 1890, the bustle was once again abandoned. The Paris correspondent for Cassell’s Family Magazine reported that the French had already discarded the dress improver in August 1888: their skirts had no drapery, but fell straight and flat to the ground.

Dressmakers and Home-dressmaking. During the Victorian period, most clothes would be made up at home by the women of the family, or made by a professional dressmaker, who could be anywhere between a high fashion couturier, complete with fashion house, and the village seamstress: it would all depend on your skill level, how much money you had and how complicated the dress was to make.

There were a small number of ready-to-wear garments available to buy. These were normally items that required little or no individual fitting, such as underwear bought in standard measurement sizes, or mantles and capes where one size would fit most customers. Some partly made garments were also available for sale. These were often dresses where the skirts would be made up, and the matching fabric sold alongside it to be made into the bodice and rest of the dress, as this was the part which would need individual custom fitting.

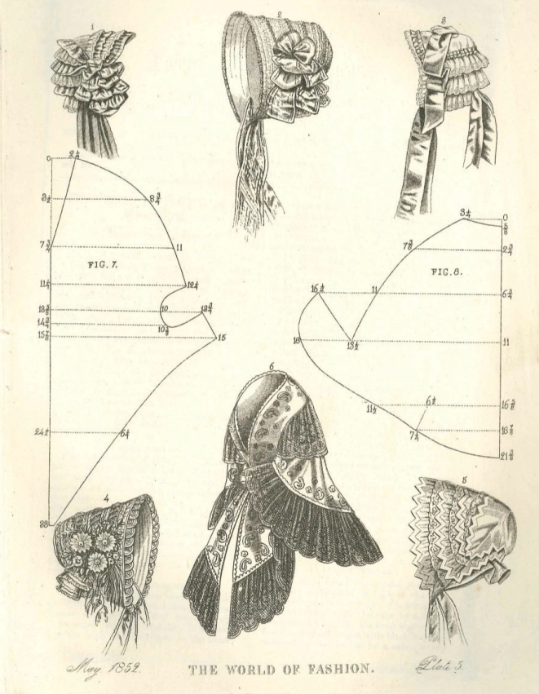

Home dressmaking was greatly assisted by the emergence of paper patterns, which were published in ladies’ fashion magazines or could be sent away for by post. An early example of this can be seen in a mantle pattern from The World of Fashion, 1852, which has instructions in the main text for drafting at full size, and instructions on how to make the item up. Many other magazines followed their example, such as our example from The Ladies’ Treasury in 1876 which gives instructions on how to send away for paper patterns. Readers were told they could order plain paper patterns free of postage cost, and were assured that ‘no difficulty can arise in making them up’.

Fig. 11.7. Pattern for a mantle given in The World of Fashion, 1852, with guidance provided in the magazine text

Such was the demand for these patterns that it was made clear that ‘Madame Vevay will be unable to execute an order under four days from receipt of letter’. Many dresses were also remade, or altered, rather than being made completely from scratch. Fabric, especially in the quantities required for some Victorian dresses, was an expensive commodity, and it was this rather than the labour time of the dressmaker that represented the most investment. When styles changed only slightly then dresses would be adapted, to update to the latest style of sleeve shape or trimming arrangement. This was a much more economical way of remaining fashionable than buying a completely new dress.

Date added: 2025-03-21; views: 481;