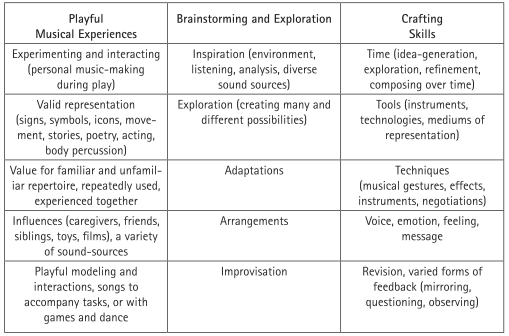

Brainstorming and Exploration. Crafting Compositional Skills

Brainstorming and Exploration.Beyond musical experiences and understandings, focused brainstorming and exploratory opportunities can also build ownership in adapting known music. As Patricia Sheehan Campbell (2010) mentioned, children do this naturally, and teachers can encourage it further. The lines between adapting known music and creating original music will blur, particularly for young children who may not recognize the ways known musics influence their own ideas. Regardless of the degree of originality in a child’s musical creation, their feelings of originality are often empowering and deeply meaningful. According to Sir Ken Robinson (2001), the development of one’s creativity can take shape in many ways. Children make use of the materials and tools in their environment and assign meanings to manipulate them (Robinson, 2001). Young children may use invented songs to communicate their feelings or to narrate their environments (Barrett, 2012) as they make meaning for themselves and of themselves (Kaschub & Smith, 2017).

The ways children interact with others impact improvisation and development of musical material (Barrett, 2012), which may not only lead to composition, but can exist as composition. Children might repeat and elaborate on rhythmic or melodic ideas and draw heavily from known musics. These adjustments and arrangements from known music demonstrate growing abilities to think divergently. Educators can task children with varied adaptations and arrangements, creating opportunities to experiment with sounds inspired by their experiences. According to Burnard (2012), young children enter the classroom as music-makers who create and bear their own cultural experiences and music educators can use this as a point of connection.

Rob Deemer (2016) noted that pre-service music teachers should work with composers to gain skills in composing. In-service music educators might also seek some composers for residencies and guest workshops, particularly if they are playful and flexible. These partnerships can take place once or over a period of time and may be fruitful depending on program goals.

In an artist collaboration project described by Julia Getino et al. (2018), students began by listening to and analyzing a professional composer’s work. Following a listening analysis and guided discussion, students generated musical ideas in groups through instructional composition exercises. They then created musical ideas based on characteristics of the prior analysis. The exercises prepared students to create appealing sounds, manipulate sound sources, and consider the interactions of sounds.

These activities provided pathways they could return to when composing their own works. It is important however, that when children compose, composers are aware of their support role rather than directive. Children should focus on creating the most possible ideas, along with most different ways of doing them, rather than a best way, in line with Baer and Kaufman (2012) and Torrance (1965) creative categories of fluency, flexibility, and originality. Brainstorming exercises should also be separate from processes of editing and refining, as brainstorming can be most fruitful with open attitude of “anything is possible.”

Crafting Compositional Skills.Children grow from continuous opportunities to generate, organize, and refine musical ideas. One’s accumulation of experiences can build musicianship skills. In this section I discuss continuous opportunities to compose. I also discuss structural considerations, and topics of meaning and expressivity.

Continuous Opportunities. Although music teachers may provide some opportunities for young children to compose, the time spent on composition is sometimes minimal. Stauffer (2001) noted that time, tool, and technique all interact in children’s composition processes. In terms of time, children need time to compose, as well as many opportunities to practice composing over time (Bucura & Weissberg, 2016-2017). Stauffer (2001) found that time is important for several reasons that include familiarization with the medium (e.g., software, instruments), development of skills and gestures, and practice. Children need continuous opportunities to revise and develop their musical ideas; therefore, it may be important they find ways to retrieve musical ideas over time.

According to Getino et al. (2018), it can be important to create a score of some kind, naming two reasons: “to help students remember tomorrow what was done today and to be able to reflect on paper what has been put together” (p. 33). The score, however, can be considered with flexibility. Standard notation will be unfamiliar to many children—it can restrain composition even among those who know and use it. Very young children may not be skilled in the coding system of language either, in which case other means of representation can be helpful. Imagery, movement, recordings, and invented notation (e.g., Barrett, 2002), however, are some methods of documenting musical ideas that can be accessible and retrievable to young children. These representations may promote expressivity as well, as children can focus on appealing sounds and expressive representations rather than focusing on a system of representation.

Structure. In addition to aforementioned experiences and competencies that can form a basis for conceptualizing music, Folkestad (2004) also noted that these interact with cultural practices, tools, instruments, and instructions. Music spaces—including in the home— can provide selections of sound sources, including a variety of musical instruments and software. Whether children have refined playing skills on these tools is mostly beside the point—children will enjoy strumming or picking guitar strings, for example, or identifying melodies on a keyboard. They may also be inspired by the timbre itself, or the gesture involved in making the sound (e.g., plucking, strumming, hitting, blowing, dragging). Such experiences may even promote an interest in further learning what sounds the instrument offers, thus inspiring skill development.

Recorders are sometimes required in elementary music classes and can enable children to melodi- cally create with a different timbre and experience from that of voice, xylophone, or the like. Yet other types of instruments, slide or tin whistles for instance, may also be appealing to children and can be interpreted as a novel and inspiring sound source. Other sound sources less commonly experienced can play similar roles, like alto recorders, accordions, harmonicas, and steel pans, which may be borrowed when purchase is not possible.

In addition to engaging sound sources made available to children, a stimulating environment in general is an important part of some early childhood education approaches, for instance in the Reggio Emilia approach (Miller & Pound, 2011). In addition to a wide array of interesting and available sound sources, displays of works-in-progress can foster dialogue about learning and creativity. Such displays may include plans in the form of maps, formulas, or iconic or symbolic representations; invented notation; imagery like photographs, collages, screenshots; or comments from peers or others. Stations, for example for listening to recordings, to gather instruments, to make music, or to dance and move, can also foster a creative environment. Displays and stations can document works and processes, promote dialogue, make space, and therefore communicate value for children’s ideas. These can reinforce to children that their ideas should be taken seriously by adults and by themselves.

Compositions can draw on a wide array of additional environmental influences to spark imagination, for instance spaces outside the classroom and in nature. Children love to sing in a resonant stairwell, on an auditorium stage, or in an enclosed space all their own (e.g., under a table, in an alcove, behind a curtain). When in nature, bird song, traffic, weather, and the like can suggest musical ideas. In a classroom, natural scenes can also be evoked through pictures, video, and descriptive storytelling, for instance beach scenes, neighborhood, farmland, highway, pond, and so on. Interaction with the environment can occur through physical exploration (e.g., running, twirling, or rolling on grass; dripping water through fingers; squishing mud or slime) and exploration of sound and form (e.g., loud, soft, echo, loop, cycle).

Interaction with differing spaces can be particularly inspirational, especially when children are liberated to explore the full extent of possibilities in order to draw boundaries for themselves before focusing ideas (Bucura & Weissberg, 2016-2017). It can be difficult for adults to allow children to explore such boundaries (e.g., the loudest possible sounds, the biggest possible group, the most possible instruments), but these experiences are often necessary in order for children to then mediate their own approach that they chose for themselves.

Meaning and Expressivity. Rob Deemer (2016) referred to composition as a personal act that blends both emotion and intellect. Compositions can lack emotion if children feel unsafe expressing themselves. Beyond exercises and activities intended to build compositional skills, it is important that teachers and caregivers value space and time for children to compose their own, unrestricted music. In these instances, composing can allow children to articulate their feelings and uniquely express themselves. As Michele Kaschub and Janice Smith (2017) stated:

The act of composing transcends the limits of verbal and mathematical representations and allows children to explore sound as a means for sharing who they are, what they think, and what they feel about their experiences in the world. It invites them to draw on the full breadth of their musical skills and understanding to create music that represents their unique insights. (p. 13)

When children autonomously compose, teachers can emphasize the goals of voice and expression by providing prompting inspirations rather than skill-building directives. These may include open-ended prompts involving art, dance/movement, scenes, stories, moods, or characters meant to evoke prior experiences, interpretations, and feelings.

Teacher Role. Teachers must consider their roles sensitively in relation to children’s creative works. In the Reggio Emilia approach, creativity grows when teachers refrain from prescription and are instead sensitive and attentive observers, responders, and interpreters (Anttila & Sansom, 2012). Music education scholars recommend similar facilitation approaches, particularly learner-centeredness (Huhtinen-Hilden & Pitt, 2018). Teachers must recognize children’s differentiated understandings and participate in creative interactions with them (Malaguzzi, 1998).

Young children are often excited to share their work. Although some children will feel inhibited by surveillance or competition (Amabile et al., 2018), children often seek teacher approval. As an extrinsic motivator, teacher approval can congest intrinsic drive. Unspecific praise can stifle creativity and promote a fixed idea of musicianship (Dweck, 2007) or talent. The teacher-student hierarchy can result in hesitation to take risks and to trust one’s own decisions. Getino et al. (2018) noted the teacher’s role should allow students autonomy while being available for suggestions and reflections. According to Getino et al., this helps establish teachers’ relationships to, and understandings of, students’ works and can help move processes along when children feel unsure or stuck. Teachers must therefore provide sensitive, specific feedback while consciously making space for children to trust and value themselves.

Teachers should also collaborate sensitively and flexibly to aid in bringing children’s intentions to sound (Kaschub & Smith, 2017). Teachers and caregivers can compose their own music (Bucura & Weissberg, 2016-17; Nagy, 2016) and welcome children’s feedback on it, therefore role modeling value for composition as a human act, as well as respect and appreciation for varied perspectives. This communicates that composing music is for everyone. In this way, teachers can also disrupt the teacher-student hierarchy. According to Deemer (2016), teachers and children should collaborate as well, which can occur as a whole-class or small group activity.

Feedback, Reflection, Revision. Artistic outcomes are typically the result of long-term work to realize one’s intentions through processes of revision and refinement. While musical exploration and brainstorming are important steps toward idea generation, processes of receiving feedback (even one’s own), and reflecting on it with revision, are important steps for children to grow as composers.

Children should reflect on their processes and products (Barrett, 2000-2001). Reflection allows children to consider the overall effect in relationship to their intentions. Kaschub and Smith (2017) noted that before considering what revisions they might make, children should articulate reasons for them. Children can revisit their original inspirations and intentions. For instance, Does the piece sound the way I wanted? What about it works well? and What would happen if. . .? Music teachers facilitate reflection with such questions, encouraging children to experiment, elaborate, create alternate possibilities, or create anew. Children should describe their compositions and reflect on both processes and products (Barrett, 2000-2001), which they can do in a variety of ways: with teacher or peers, self-reflection (written, audio, video), in pictures, or discussion. Over time, reflective processes may become habitual and self-initiated.

As Peter Webster (2012) described, revision involves improving composition by making changes to the original. Webster believed the composer must first consider their musical ideas worthy of such feedback, which teachers can bolster by showing interest and asking questions. Young children, who experience the world in immediate ways, may also not choose to edit their music. Young children tend to write music and stop at a point of satisfaction without looking back. Rather than return to finished pieces, they may prefer instead to create entirely new pieces, one after another. Despite feelings of completion for each, they may unconsciously return to prior musical ideas that reoccur in subsequent compositions (Stauffer, 2013). In assessment, teachers can consider a student’s many compositions, over which time a refinement of skills might be noted that are not apparent when considered individually.

Feedback should vary, including self-, peer-, and teacher-assessments with differing degrees of formality. With an end-product that is not yet realized and learning that can occur in unexpected ways, assessments must be clear yet flexible. As Pamela Burnard (2012) noted, assessments are one way by which institutions legitimize and normalize their values. Assessments will therefore communicate to children why composition is valuable and in what ways. Young children may not always skillfully consider others’ perspectives. As they age and grow in composition skills, they can improve in considering others’ perspectives, and may write music with intended listener interpretations (Kaschub & Smith, 2017).

Younger composers, however, may be surprised or disappointed if a peer does not understand their intention or musical references. Peer feedback can provide valuable perspective to the composer if they are prepared to consider it. Children can share reflections, successes, and suggestions as well as pose challenges (Getino et al., 2018). Children must gain these skills, and such interactions can build a community of support, safety, and encouragement. Such interactions also have the potential to negatively impact the self-concept of young composers and therefore, must be carefully guided. Young children can successfully provide observational feedback that avoid opinion, for instance, “I noticed . . ” or “I heard . . . ” These comments can contribute to analytic skills for listeners while providing interpretations to the composer without the judgment of “I liked . . . ”

While reactions, questions, and impressions others have about a student’s piece can influence revision, children will have varying degrees of readiness for feedback (Webster, 2012). Music teachers must consider feedback sensitively for each student, gauging their readiness to receive it, to what degree, and how so. Similarly, peer feedback involves sharing compositions. When sharing, children should have opportunities to represent their compositions in a variety of ways (e.g., visual representation of all variety, recordings, performances, embodiment of musical ideas, verbal description). While many young children will be eager to share, others may not. If a student is hesitant, they might instead explain ideas or describe their music. Sharing compositions may be especially difficult for older children, particularly if the peer group feels unsafe or is new. Sharing should not be forced but continually invited and encouraged, and role modeled as safe, respectful, and supportive.

Teachers should also be prepared for children to create in unexpected ways. When comfortable with composing processes, children may develop skills in communicating feelings (Anttila & Sansom, 2012). It is important to bear in mind that the composers are the experts of their own feelings. Children may express worrying feelings or themes that the teacher must then navigate, particularly in songwriting where lyrics might provide an explicit message, for instance trauma, neglect, or violence. Teachers must then prioritize the child’s well-being while striving to maintain a safe space for creation and expression, necessitating careful consideration of children’s expressions alongside their own legal and ethical responsibilities to them. Through processes of playful musical experiences, brainstorming and exploration, and crafting compositional skills, children will grow in their abilities to express themselves musically. Each process necessitates thoughtful considerations (see Figure 25.1). When grounded in an ethic of care, children will be nurtured as composers.

Figure 25.1. Early childhood composition processes

References: Amabile, T. M., Collins, M. A., Conti, R., Phillips, E., Picariello, M., Ruscio, J., & Whitney, D. (2018). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Routledge.

Amabile, T. M., & Tighe, E. (1993). Questions of creativity. In J. Brockman (Ed.), Creativity (pp. 7-27). Touchstone.

Anttila, E., & Sansom, A. (2012). Movement, embodiment, and creativity: Perspectives on the value of dance in early childhood education. In O. N. Saracho (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on research in creativity in early childhood education (pp. 179-204). Information Age Publishing.

Baer, J., & Kaufman, J. C. (2012). Being creative inside and outside the classroom: How to boost your students’ creativity—and your own. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral. proquest.com

Barrett, M. (1996). Children’s aesthetic decision-making: An analysis of children’s musical discourse as composers. International Journal of Music Education, os-28(1), 37-62. https://doi. org/10.1177/025576149602800104

Barrett, M. S. (2000-2001). Perception, description, and reflection: Young children’s aesthetic decision-making as critics of their own and adult compositions. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 147(Winter, 2000/2001), 22-29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319382

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 246;