The Impact of Improvisation. Expanding on Melodies

Jazz ensemble teachers at all levels can use melodies in their ensemble repertoire to highlight good ideas for composing melodies. For those using jazz ensemble method books, there are regular opportunities for improvisation built in, alongside the introduction of new exercises and music. Within the method books, new melodic ideas are introduced, and the length of exercises and pieces increase. Also, the director may choose to have the ensemble read sheet music at an appropriate level. The new melodic ideas provide a good setting for improvisation and composition ideas. The increased length of the method book pieces facilitates an introduction to musical form and chord progressions, as discussed and presented in the method books. Students will begin to realize possible connections to their own compositions.

Student improvisation could include small group or collective improvisation to establish student confidence. Those students that are additionally proficient may want to improvise on their own. The same approach can be applied to the connected composition activity, with the added benefit of using some melodic and rhythmic ideas from the group improvisation, or from the soloists. This is an opportunity for the director to audio record the class session to later notate and share the ideas shared by the students. Alternatively, the students could listen to the prior ideas and create their own group composition sessions. The connections between composing and improvising should become apparent with each exercise.

While the previous blues-based exercises offer a good introduction to the call-and- response approach and overall form, it is important for the director to model improvisation and continue to provide sample melodic and rhythmic ideas for students at this level. Of great importance is taking the time needed for improvisation. The modern j azz ensemble method books provide online access to recorded practice tracks, complete with rhythm section. With guidance, and creative encouragement and motivation from the jazz ensemble director, students can practice improvisation on their own and arrive at rehearsals with new ideas and confidence for improvisation.

Improvised solo ideas can contribute to compositions. If a cell phone or other recording device is available, students can record their improvised solos in rehearsal, or during their own practice time. The music practice app SmartMusic includes some jazz music, and can be used for improvisation as well. The solos could then be transcribed for use in future compositions. Also, the transcription of solos from jazz recordings is an excellent and frequently used method to develop improvisational and compositional ideas.

Expanding on Melodies.Melodic development is important to the composition process. One next step in melodic writing is to create riffs. Riffs are melodic patterns comprised of a limited number of notes, then repeated (Pick & Cullum, 2010). In the late 1920s j azz ensemble, this practice was heard in the solos of Louis Armstrong (Pick & Cullum, 2010), in the music of Walter Page’s Blue Devils, and notably in the 1930s with the Bennie Moten Orchestra, with his riff-based piece “Moten Swing” (1932) (Tucker, 1985), among others. William “Count” Basie played piano on the recording, and following Moten’s death in 1935, the orchestra ultimately became the Count Basie Orchestra (Pick & Cullum, 2010; Tucker, 1985).

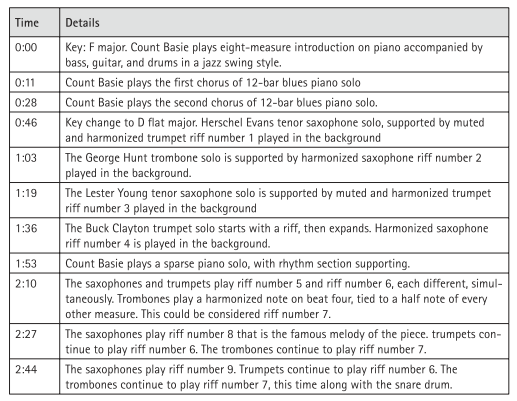

The director can create a guided listening exercise based on various riff-based jazz pieces. The Count Basie piece “One O’Clock Jump” (1937), performed by the Count Basie Orchestra, is a suggested starting point. The piece is a 12-bar blues, the majority of which is built on riffs and improvisation until the familiar melody near the end. A sample listening guide based on the riff figures and improvisation in “One O’Clock Jump” is shown in Figure 33.5.

Figure 33.5. Listening Guide: Riff figures and improvisation in “One O’Clock Jump”

Students can identify various elements found in “One O’Clock Jump” including style, form, articulation, dynamics, timbre, etc. Class discussions can be initiated around specific questions, such as of how many different riffs exist, which instrumental sections play the riffs, how the riffs align with the improvised solos, how the rhythm section interacts with the riffs, etc. Open discussion and re-listening to the music can spark compositional ideas. Additional riff-based pieces recommended for listening can include:

- “Moten Swing” (1932), composed by Benny Moten and recorded by Count Basie and His Orchestra

- “Sing, Sing, Sing” (1937), composed by Louis Prima and recorded by Benny Goodman and His Orchestra

- “Jumpin’ at the Woodside” (1938), composed by Count Basie and recorded by and Count Basie His Orchestra

- “In a Mellotone” (1940), composed by Duke Ellington and recorded by Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra

- “C Jam Blues” (1942), composed by Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra

As a composition activity, the director can select a key signature and time signature for the group, and students can divide into sections to compose their own two- measure riffs. The process can be reinforced by singing their riff ideas, playing them on instruments, then committing the ideas to the composition.

At this point, beginning jazz composers should be able to contribute to large group or small group 12-bar blues compositions. Once notated on paper and completed, the students should play the pieces in rehearsal. More important than performance at this point is providing opportunities for the students to make informed musical decisions that contribute to the entire compositional process, and to have decision-making authority with the process. The rehearsal should be audio-recorded and will provide an opportunity for the students to read and hear the new melodic riffs alongside their peers’ compositions and to have a first-hand view of what is effective for their instruments. After the rehearsal/recording of the music, allow the students to ask questions, offer suggestions, make edits/changes, etc., while providing their justification for such changes. A list of the larger edits should be made for a final rehearsal. This could be a transformational experience for the young composer.

Instrumental Workshops.Instrumental workshops are an opportunity for student composers to additionally understand the various instruments and timbres available to them. In this context, an instrumental workshop can build upon guided listening lessons. Specific topics can be presented in the context of the music played and/or by instrumental section, to include the range and timbre of all traditional jazz instruments, an introduction to brass mutes, articulation styles, and a discussion of any jazz-related notation used by composers. Added information should be provided about the rhythm section instruments piano, guitar, bass guitar/double bass, drum set, and auxiliary percussion. The director can facilitate these discussions by presenting the music being discussed via the available online performances of jazz ensemble originals and arrangements, presented along with the musical scores at various publisher YouTube channels. The visual aspect of seeing the score, and isolating examples common to jazz is a valuable practice. The examples can be selected via the various music grade levels at and beyond their current performance levels.

Another possibility is inviting a guest jazz ensemble that is more experienced than your own group, or individual musicians to demonstrate the instruments via their music. This experience could provide musical perspective and may be good motivation for the student composer to see advanced possibilities. The workshops can provide ongoing discussions as the middle school jazz ensemble develops musically. Future areas can be style-based, or composer based. Also, this process reinforces the importance of purposeful listening to music with the compositional process in mind.

Moving on to Bebop.In this section, melodic and rhythmic composing in the bebop style will be presented. Intermediate composers in the jazz ensemble can quickly build upon their past experiences. Guided and independent listening experiences should continue. Teacher- led class composition can continue; however, additional student-centered small group and individual composition projects ofvarying lengths should be created at this level.

Additional melodic and rhythmic interpretation and composition activities should be presented via multiple styles. The bebop style is commonly included in jazz ensemble method books. When learning bebop style, extended harmonies, chromatic passages featuring added eighth note and triplet rhythms, and added articulation present new challenges for the intermediate level jazz composer. Listening to the pioneering bebop era musicians Charlie Parker (alto saxophone) and Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet) is essential. Many other musicians followed their lead with this landmark musical style change.

As will be discovered by listening to many small groups/combos and bebop era musicians, the melodic parts were doubled or harmonized by one or two instruments. Similar to early small group jazz music, jazz combo pieces in the bebop style typically feature a statement of the melody, called the “head,” which is often repeated. Following the statement of melody, the musicians individually improvise over the chord progressions. Following the solos, the head is repeated, sometimes ending with a tag or extension to close the piece. The music was sometimes composed over the familiar blues chord progressions, an existing 32-bar song form popular with Tin Pan Alley composers of Broadway musicals and/or show tunes, or other chord progressions.

The selection of medium groove (medium tempo) pieces such as Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time” (1945) and “Billie’s Bounce” (1945) provide a good introduction to the bebop style. The musicians on these pieces are Charlie Parker, alto saxophone; Miles Davis, trumpet; Bud Powell, piano; Curley Russell, bass, and Max Roach, drums (Burlingame, n.d.). Now’s the Time and “Billie’s Bounce” have similar chord progressions, which provides familiarity to the listener and to the developing composer. In this way, perhaps the creative focus can be dedicated to melodic and rhythmic ideas.

“Now’s the Time” features a 12-bar blues form that should now be familiar to the students. The director should play a 12-bar blues progression in F major, or have the rhythm section play the 12-bar blues progression in F major from an existing piece to remind the students of the progression. The piece is very accessible and does not feature the potentially intimidating fast tempo of many other bebop pieces. The students will immediately notice the smaller combo instrumentation, as compared to the jazz ensemble. Upon listening to the recording, the following sample essential questions can be asked and discussed:

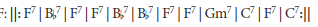

- Following the eight-measure introduction, does the 12-bar blues chord progression in “Now’s the Time” sound the same, or different than previous examples? If it sounds different, how? Some differences include the addition of the IV7 chord in measure two, the use of dominant seventh chords throughout rather than triads, as such:

- In what way does the piano comping style interact with the melody?

- In what way does the piano comping style interact with the soloists?

- How does the walking bass style impact the first statement of the melody?

- How does the walking bass style impact the solo sections? Does the bass playing differ during the piano solo?

- In what ways does the drum set interact with the melody?

- In what ways does the drum set interact with the soloists?

“Billie’s Bounce” features the same key and similar 12-bar blues form with a slightly faster tempo but is still technically approachable. Essential questions for the students can include:

- What are the similarities between “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce”?

- What are the differences between “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce”?

- How is the 12-bar blues chord progression different in “Billie’s Bounce”?

- Did you notice different chords in measure eight? If so, what are they? (director guidance may be needed to explain the ii—V—I turnaround in measure eight to measure nine)

- How does the piano comping differ from the comping in “Now’s the Time?” How does the different comping style impact the music?

- What are the differences in the drum set playing?

During Charlie Parker’s and Miles Davis’ solos on both pieces, the interaction between the soloist and the rhythm section should be emphasized. Sample essential questions specific to the solos can include:

- On “Billie’s Bounce,” how would you describe the development of Charlie Parker’s alto saxophone solo?

- How would you describe the development of Miles Davis’s trumpet solo?

- What types of rhythmic and melodic ideas did Miles Davis use on his trumpet solo?

- In what ways does Miles Davis change the musical activity in the two choruses of his solo?

- What rhythm section instrument(s) interact the most with Charlie Parker during his solo? Why do you think so?

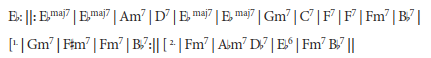

“Groovin’ High” (1944), composed by Dizzy Gillespie, was composed using the same chord progression and 32-bar song form of “Whispering” (1920), composed by Paul Whiteman (Burlingame, n.d.). The eighth-note rhythms emphasize the importance of jazz articulation throughout. The 1947 Carnegie Hall performance of “Groovin’ High” featured Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet; Charlie Parker, alto saxophone; John Lewis, piano; Al McKibbon, bass; and Joe Harris, drums. The “Groovin’ High” chord progression, after the recorded introduction (and with a ii-V turnaround at the end) is as follows:

The sample essential questions for the students can include many of the same used for “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce,” in addition to the following:

- How is “Groovin’ High” similar to “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce?”

- How is “Groovin’ High” different than “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce?”

- How does the form differ from “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce?”

- How does the chord progression differ from “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce?”

The listening activity can greatly inform the student composition experience, and the music selections are certainly the decisions of the jazz ensemble director. After listening to examples of the bebop style, the intermediate level jazz composer can begin to incorporate added ideas and approaches. The application of specific musical parameters is suggested, such as increased or varied tempi, inclusion of eighth and sixteenth notes, use of riffs, use of contemporary harmonies and chord progressions, etc. Students can continue to write their melodic ideas, with close attention to the form and the space needed for improvisation. The bebop style presents an opportunity to compose for the smaller combo instrumentation, however, the concepts can be set to the full jazz ensemble as well.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 191;