Alcohol-Socioeconomic Impacts (Including Externalities)

Depending on the cultural context and particular circumstances, the same drink of alcohol can generate a feeling of benign content, or moroseness, or stupor. The immediate health benefits for the individual may also be benign (or even beneficial), or the drink may result in injury or death - in the short run from accident or in the long run from one of the diseases alcohol can precipitate. The consequences for others may also be benign or beneficial, or damaging or mortal from violence or collateral accident. Someone may be born as the result of intentional or unintentional impregnation.

The loss of production due to lower workplace productivity or non-attendance from drinking alcohol may cause financial loss to the drinker and possibly to others. Alcohol may, or may not, generate additional costs in many sectors of the economy, especially in the criminal system, in the health system, and in the transport system. The national budget probably gains from the specific tax it levies on alcoholic beverages, but this levy may, or may not, cover its costs from the consumption of alcohol.

The impact of alcohol consumption is so multifarious that it is not easy to track all its social and economic impacts. This review confines itself to those to which social costs of alcohol misuse studies have paid most attention, excluding the burden of disease caused by alcohol which is covered in this encyclopedia by Rehm.

The framework used is that of the WHO report, International Guidelines for Estimating the Costs of Substance Abuse (Single et al, 2003), and related and subsequent studies, although some of the technical issues, such as the valuation of life, counterfactual hypotheses, and discounting, are not considered here.

As the opening sentence reminds us, the social and economic impact of alcohol is affected by the cultural context, even though the physiological impact may not be. This means that each country, or culture within a country, has its own quantitative and qualitative particularities. This entry deals with the heterogeneity by including in its bibliography recent country-specific studies (especially cost studies, because they look at most dimensions of the impact).

Following brief discussions on externalities and irrationality, the main areas of impact are dealt with in alphabetical order, because their relative significance will vary from country to country.

Externalities. The social cost of an activity is the total of all the costs associated with it, including both the costs borne by the economic agent involved and all costs borne by society at large. This includes the costs reflected in the organization’s charge (price), which covers the use of the various resources (including labor capital and risk as well as natural resources) excluding taxation, together with the costs external to the firm’s private costs. If social costs are greater than private costs - the costs of purchase - then a negative externality is present.

When the market economy is working effectively, and there are no external social costs, rational consumers will purchase and consume the product only if it is more valuable to them than the price paid for it. In this case, society is better off since the consumers deem themselves better off from the transaction, and society is no worse off, since it has traded off the social costs of the consumption for the payment, which embodies the ability to purchase other products with equivalent social costs.

There are all sorts of subtle assumptions embodied in this analysis: Public health analysis often worries about the equity in the distribution of income - the power to purchase. But even if those assumptions hold (near enough), alcoholic beverages are one of a number of products for which the purchase price cannot generally equal social costs because the social cost of each unit of consumption varies greatly.

Thus the social cost of the first drink in a session may reflect the private cost, but later drinks may generate additional social costs in poor health, material damage, public and private outlays that were ignored when the drinking decision was made, violence to others, and even death to the drinker or, in the case of motor vehicle accidents and the like, to innocent bystanders.

As a later section discusses, taxation and other public policy measures aim to reconcile in one way or another the inconsistency between the purchase price and social costs. However, there is still likely to be a substantial difference for at least a number of significant ingestions.

A useful term is misuse for occasions where the consumption generates outcomes that were unintended by the consumer and not taken into account when the purchase or drinking decision was made. It is sometimes preferred to abuse in order to emphasize that much alcohol consumption is useful, in the sense of its social impact being benign or even (mildly) beneficial.

Irrationality. The previous discussion has assumed that consumers are acting rationally, taking into consideration all the costs of the consumption that affect them (although they may discount costs in the more distant future).

However, it is not immediately obvious that rationality applies when there is drunkenness or addiction. Economists explore this by using a theoretical definition of irrationality where consumers show time inconsistency between decisions, as for example when they go into a bar to have three drinks, change their minds in consequence of the resulting euphoria and drink more, and the following day regret the change of mind (Ainslie, 1992; Frederick et al, 2002; O’Donoghue and Rabin, 2003).

It is unclear how to define externalities in such circumstances. The tendency has been to ignore such irrationality, but increasingly cost of alcohol studies need to address it, incorporating it in a rigorous way consistent with the theory.

Crime. Pernanem et al. (2000, 2002), based on Goldstein (1985), propose four models (modes might be a better word) to account for alcohol-associated crime.

1. The pharmacological model, in which intoxication encourages the commission of crimes which otherwise would not have been committed.

2. The economic means model, in which crimes are committed to fund alcohol consumption.

3. The systemic model, involving the illegal economy, as in unlawful brewing or distilling or sale of liquor.

4. The substance-defined model, where actions are defined as being criminal by laws which regulate drug use, such as drunkenness in a public place, supplying underage or drunk people (if that be illegal) and drunk-driving.

Note these apply also to illicit drugs, for which modes 3 and 4 are more important than for alcohol.

This crime causes social costs, both directly via damage to property and individuals but also with consequent costs to the public purse for policing, justice and corrections, transport management, and indirectly when it adds to concerns about community safety and security.

Estimating the attributable fractions (the proportions which alcohol causes) for criminal activity is much less advanced than for disease. Because law, practices of enforcement, and culture vary by country, fractions cannot be easily borrowed from other jurisdictions. (Indeed care is also required in generalizing research findings on the relationship between crime and alcohol.)

Harm to Others. As well as affecting the health of its drinkers, alcohol can affect the health of others. These effects include:

1. Children born as the result of an unplanned conception as a result of intoxication (it is not obvious how to deal with this);

2. Fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects, said to be the major source of mental illness and behavioral disorders, and generating on average a large public cost during their lifetime (Harwood, 2000);

3. Pain and suffering, abuse, violence, injury, and death experienced by those close to the drinker;

4. Pain and suffering, violence, and death including from motor vehicle accidents, experienced by the wider public.

There are rarely good estimates of these phenomena, and the incidence and costs vary from country to country.

Motor Vehicle Accidents. As well as injury and death from motor vehicle accidents caused by alcohol consumption, there is damage to cars and property, the costs of law enforcement and prevention (which may include road design), and the costs of administrating the insurance system. (There are also costs in the resulting travel delays.)

Motor vehicle accidents are particularly onerous, but there are other types of accidents. Industrial accidents caused by alcohol are covered in the next section.

Production Losses. Drinking alcohol may result in production losses from the following:

1. Reduced workforce size as a consequence of death or premature retirement;

2. Absenteeism from sickness or injury;

3. Reduced on-the-job productivity from sickness or injury and accidents.

Alcohol misuse may also cause loss of production in the unpaid household sector and in other non-market activities. Although the informal economy is not included in the standard measures of market output (such as GDP or GNP), the losses or production in it caused by alcohol misuse may be significant.

Public Spending. Most of the above-mentioned events impact to some extent on public spending (or, for those countries that depend more upon private provision, on the private insurance system). Such an impact is a classic externality, because it is unlikely to be taken into account by the drinker.

Among the most significant sectors affected by additional spending are costs to the health system (at every level from prevention to advanced tertiary specialties, but also for nursing care later in life), social security or other forms of public income maintenance, traffic management, and also to policing, justice, and corrections.

Taxation and Public Policy. Historically, specific taxes on alcohol were imposed because they could be readily collected at brewery, distillery, or port. (There are greater difficulties collecting excise from small vineyards.) Later in some but not all jurisdictions, the justification for special duties shifted from convenience to a notion of the propriety of taxing sinful activities.

More recently, in some jurisdictions, alcohol taxes have been justified by the arguments that raising the cost of alcohol better reconciles the private cost and social cost of alcohol consumption. If so, pure logic might conclude that the level of taxation should be related to the quantity of absolute alcohol rather than the value of the drink, imposing more heavily on low-value drinks. An extension would be to focus on the minimum cost of alcohol, structuring the excise to maintain a minimum cost of absolute alcohol, where some of the worse social costs occur (Easton, 2002).

However, no country has an economically rational alcohol taxation regime, and revenue considerations still remain as important in its design as political and cultural considerations.

Moreover, as previously mentioned, the divergence between private and social cost varies from drink to drink, so a taxation regime cannot be perfect. Therefore, other public policy measures have to be implemented. Insofar as such policy measures are effective, there would be a reduction in the divergence between private and social cost, and the optimal excise duty would be lower than if the policies are ineffective.

Conclusion. The impacts of alcohol consumption are manifold, and it is not practical to list them all. The ones discussed here are generally those which are known to be largest in quantifiable terms, as measured by their impact on GDP (or GNP) the standard measure of the aggregate output produced in the formal economy (generally valued at market prices).

This approach asks what of the available production had to be diverted to deal with the costs of alcohol misuse. (Technically it is an estimate based on supposing that if alcohol misuse had not occurred, what additional resources would have been available for consumption and other purposes.)

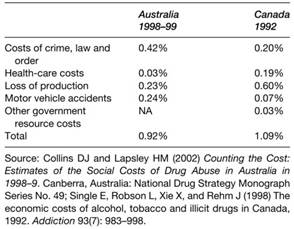

Table 1 provides estimates for two countries of this (tangible) social cost of alcohol, as a proportion of GDP. The estimates come from studies that broadly conform to the International Guidelines (Single et al., 2003). They do not include estimates of the intangible costs, arising from death, injury, and poor-quality life that alcohol misuse generates (avoiding, among other things, the problem of valuing life). Nor do they include the impact on the informal economy, because there is no measure of the aggregate value of its output (the equivalent of GDP).

Table 1. The (tangible) social costs of alcohol as a proportion of GDP

In each case the costs are estimated to be near 1% of GDP, the implication being that without alcohol misuse effective GDP would be 1% greater. However, the increase in GDP per capita would be lower, depending on the mortality impact on the population.

Note that despite using the same international guidelines, there are considerable differences between the subtotals, only some of which may be explained by classification differences or by the different cultures and institutional arrangements of Australia and Canada.

Nevertheless, while other countries may have different social costs of alcohol misuse, representing the waste from drinkers not taking into consideration the social consequences of their decisions, the magnitude as a proportion of total output is likely to be significant. The quantification reinforces the common sense conclusion of a need for behavior change and public policies in regard to alcohol consumption in order to reduce its misuse.

Date added: 2024-03-11; views: 816;