Alcohol—Treatment. Conceptual Overview: What Is Being Treated?

Alcohol consumption varies enormously in terms of the frequency and amount of drinking, not only among individuals, but also over time and between different population groups. Variations in drinking affect rates of alcohol-related problems and have implications for the organization of treatment interventions.

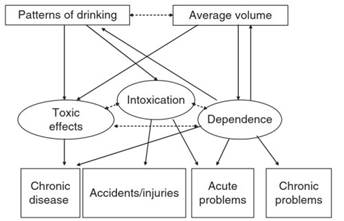

There is no sharp demarcation between social or moderate drinking, on the one hand, and problem or harmful drinking, on the other. But as the average daily amount of alcohol consumed and frequency of intoxication increase, so does the incidence of medical and psychosocial problems in a society. As illustrated in Figure 1, three mechanisms have been identified to explain alcohol’s ability to cause medical, psychological, and social harm (Babor et al., 2003): (1) physical toxicity, (2) intoxication, and (3) dependence.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram illustrating how alcohol consumption is linked to alcohol-related problems through three mechanisms of action: Toxicity, intoxication, and dependence. Reproduced from Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. (2003) Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity – Research and Public Policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. By permission of Oxford University Press

Alcohol is a toxic substance in terms of its direct and indirect effects on a wide range of body organs and organ systems. In addition, one of the main causes of alcohol-related harm in the general population is alcohol intoxication, which is strongly related to violence, traffic casualties, and other injuries. Alcohol dependence has many different contributory causes, including genetic vulnerability, but it is a condition that is often contracted by repeated exposure to alcohol. In general, the heavier the drinking, the greater the risk is of developing alcohol dependence.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the mechanisms of toxicity, intoxication, and dependence are closely related to the ways in which people consume alcohol, called patterns of drinking. Drinking patterns that lead to rapidly elevated blood alcohol levels result in problems associated with acute intoxication such as accidents, injuries, and violence. Similarly, drinking patterns that promote frequent and heavy alcohol consumption are associated with chronic health problems such as liver cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease, and depression.

Sustained drinking may also result in alcohol dependence. Once dependence is present, it impairs a person’s ability to control the frequency and amount of drinking. For these reasons, the public health response should be designed to address not only the treatment of alcohol dependence, but also the management of persons who are both harmful and hazardous drinkers. Harmful drinkers are people without serious alcohol dependence whose alcohol misuse is already causing problems to their health, whereas hazardous drinkers are people who drink in ways that increase the risk of experiencing health or social problems.

Alcohol dependence has long been recognized to run in families. There is an estimated sevenfold risk of alcohol dependence in first-degree relatives of alcohol-dependent individuals. But the majority of alcohol-dependent individuals do not have a first-degree relative who is alcohol dependent. This underscores the fact that the risk for alcohol dependence is also determined by environmental factors, which may interact in complex ways with genetics.

A variety of approaches have been proposed to describe the diverse types of alcohol dependence encountered in clinical settings (Hesselbrock and Hesselbrock, 2006), in the interest of developing specialized treatment interventions that would address the needs of different types of alcohol-dependent drinkers, commonly called alcoholics.

These include diagnostic classifications based on single characteristics such as onset age of alcohol problems (early vs. later in life), drinking pattern (continuous vs. binge drinking), family history of alcoholism, personality style, and the presence or absence of psychopathology. Multidimensional approaches combine these characteristics into meaningful clusters. One of the best known of these typologies is the Type 1/Type 2 distinction developed by Cloninger and colleagues (1987).

Type 1 alcoholics are characterized by the late onset of problem drinking, rapid development of behavioral tolerance to alcohol, prominent guilt and anxiety related to drinking, and infrequent fighting and arrests when drinking. Cloninger also termed this subtype milieu-limited, which emphasizes the etiologic role of environmental factors. In contrast, Type 2 alcoholics are characterized by early onset of an inability to abstain from alcohol, frequent fighting and arrests when drinking, and the absence of guilt and fear concerning drinking. Differences in the two subtypes are thought to result from differences in three basic personality (i.e., temperament) traits, each of which has a unique neurochemical and genetic substrate.

Babor and colleagues (1992) used statistical clustering techniques to derive a dichotomous typology (Type A vs. Type B) similar to that proposed earlier by Cloninger. The analysis identified two homogeneous subtypes that may have important implications for understanding the etiology of different forms of alcoholism.

Type A alcoholics have a later onset of alcohol-related problems, few childhood psychological problems, a less severe drinking history, and a more benign course of the disorder. Type B alcoholics have an early onset of alcohol-related problems, childhood behavior problems, parental alcoholism, co-occurring psychopathology, a more problematic drinking history, severe alcohol dependence, and a worse prognosis.

In addition to these different types of alcoholics, there are also substantial differences in the manifestation of alcohol dependence among different gender, age, and racial/cultural groups, suggesting the need for different treatment approaches. Adolescents have comparatively short histories of heavy drinking, and physiological dependence on alcohol and alcohol-related medical complications are rare. The manifestations of alcohol dependence in the elderly are often more subtle and nonspecific than those observed in younger individuals.

Date added: 2024-03-11; views: 622;