The Japanese Course of Study

The Japanese Course of Study consists of two areas: Music-Making and Appraising. Ongakudukuri, creative music-making, is considered as a part of Music-Making along with singing and instrumental playing; however, it is often combined with the area Appraising and music performance. In Japan, ongakudukuri encourages every student to participate in musical activities no matter their previous musical experience or skills on instrumental playing or note reading. In addition, ongakudukuri covers all genres of music exist in the world.

Although ongakudukuri is open to integrate any genres of music, the pedagogy based on the Course of Study places emphasis on teaching musical structure including repeating patterns, repetition, call and response, changes of music, relationships among phrases, and overlapping of more than two tunes. For example, Ravel’s Bolero is an excellent example of repetition in that it contains a rhythm repeated for 169 times (Tsubonou, 2017). Surprisingly, the piece consists of just two melody lines built atop the rhythm. Students first listen to the music to discover how the music expands, and to identify the dynamic changes and orchestration that makes the piece interesting. Next, students would use the idea that music was constructed by repeated patterns, and they would create music that has repetition. In ongakudukuri, the structural understanding of music is very important, and there should be always a strong tie between music listening and creative music-making (Tsubonou, 2019). Consequently, in ongakudukuri, elaborating on a pre-existing musical idea would become a model for students to use as they create music.

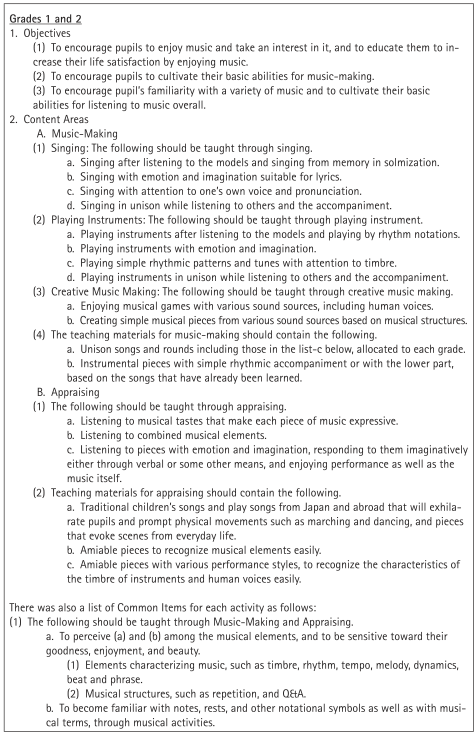

The overall objective of Japanese music education is “To encourage pupils to cultivate their sentiments, fundamental abilities for musical activities, a love for music as well as a sensitivity toward it, through music-making and appraising” (MEXT, 2007). Figure 38.1 shows MEXT in grade levels 1 and 2.

Figure 38.1. MEXT Guidance for Creative Music-Making

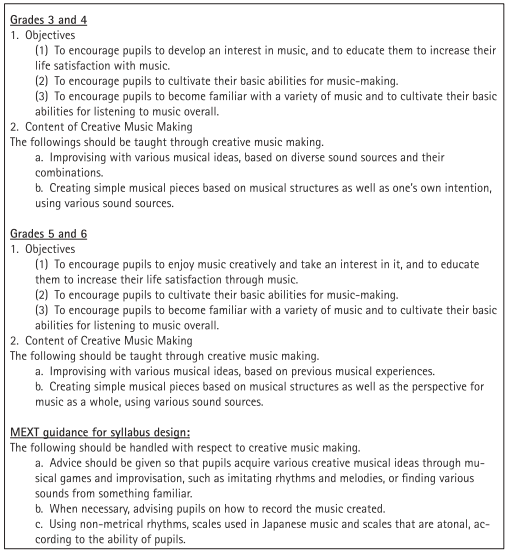

Figure 38.1. Continued

The Course of Study in Practice.Since 2007, Japanese Course of Study in Music has indicated creative music-making with detailed description of musical structure; however, the Course encourages teachers to select music locally from a wide range of musical repertoire and genres. The following three demonstrate connections between the Japanese curriculum the teaching of ongakudukuri. Each case was selected by Professor Tsubonou. For the first two cases, the teachers contributed their lesson plans and detailed notes for use in this chapterz

For the final case, Professor Tsubonou shared her lesson and video excerpts to highlight practice.

Case i. This lesson was created for fifth graders at a public elementary school in Tokyo. The lesson focused on appreciating Japanese traditional music with a special emphasis on understanding the technique of koto playing. Although the lesson focused on music appreciation, the lesson also included creative music-making. The koto (  ), a Japanese plucked string instrument, was central to the lesson.

), a Japanese plucked string instrument, was central to the lesson.

The students experienced koto playing when they were in the fourth grade. In an ensemble setting they performed “Sakura Sakura,” which is a song depicting spring and cherry blossoms. As fifth graders, the students learned various performance techniques for koto playing including staccato, scratching, and glissando. Specifically, the students played the main melody, drone, and a-i-no-te, an interjected chant. The drone part consisted of a repeated pattern called su-go-mo-ri-ji and the lesson aimed to help students understand the pattern and to let students to create a melody to fit with the drone. The lesson was conducted using the TAS model which consists of a teacher, advisor, and supporter. In this case, aside from the teacher, there was an advisor to help the teacher incorporate the pattern of accompaniment and to expand the lesson, and a supporter who performed a koto demonstration and assisted with the technical issues of playing the instrument.

The lesson of the day began by letting the children perform “Sakura” on the koto. Next, they listened to “Sakura” variations and students discovered different ways of playing the piece through the use of variation. The supporter gave some technical advice on koto playing by modeling different techniques, which the students then practiced. Students then joined groups of three to four and used the techniques they had learned from listening and form the supporter’s performance to create a melody which, per the assignment, consisted of eight notes.

The goal of the lesson was to embed creative music-making in musical appreciation. By listening to several different versions of “Sakura” and learning koto playing along with studying how the musical structure of the drone related to the melody, students were prepared to create their own variations. As an example, the teacher and supporter performed koto as a duet, with the teacher playing the drone and the supporter playing the main melody. This model helped students understand how the melody was constructed along with the accompaniment.

Students were not given specific instructions as to how they should compose; however, the teacher suggested that students focus on how to connect phrases and overlap two or more lines like the main melody and accompaniment. Students were encouraged to discuss these ideas with the members of their group and listened to other groups’ products during the last minutes of the lesson. Moreover, the students connected their group compositions and made them into a larger work.

Case 2. The next lesson aims for students to appreciate music of Japan and the world by focusing on gamelan and Debussy. In this lesson, creative music-making is found in listening and appreciation. The lesson was implemented in a public elementary school in Saitama Prefecture.

The objectives of the lesson were two-fold. First, students would experience and understand the relationship among timbre, melody, and musical expression. Second, students would gain knowledge of both Japanese and world music perspectives as a foundation for the creation of their own percussion pieces. Students were asked to listen to, perform, and discuss the traits of the music they studied in class before they worked in small groups to compose their own music.

The activities of the lesson took place in two phases. First, the teacher invited a gam- elan player as a guest, along with nine university students from Kaichi International University and Tokyo Seitoku University, to support teaching gamelan to the students. The guests performed a piece called Qubogiro at the beginning of the lesson and then the students selected instruments and learned to perform the same piece. In the second phase of the lesson, the students were asked to create music featuring the characteristics of gamelan. Each group composed, rehearsed, and presented their music in class. During the latter half of the second lesson, the students listened to Debussy’s Estampes, “Pagodes" Students discovered that there was a connection between gam- elan music and Debussy. Each group then improvised music and performed for each other.

Following the lesson, students offered the following reflections:

Student A (Female)

I found that each country owns a unique musical culture and each had a different trait of music-making. For example, gamelan had a lot of repeated notes and patterns, and between those patterns, they inserted various instruments to design the music. They also added a great many changes of the tempo.

Student B (Male)

I composed the music based on what we heard. I discovered that music has no single answer by doing ongakudukuri. In our group, we set a melody and arranged by discussion in the group. I also discovered my favorite musical style . . . gamelan.

Student C (Female)

I enjoyed listening, playing, and creating various different rhythms. [My group mate] was particularly interested in the rhythmic misalignment and overlapping. Our group purposefully added both misalignment and overlapping and added change of the speed like gamelan style.

As is illustrated by the students’ reflections, they enjoyed listening to and creating gamelan-like sound in small groups. Video of the students’ gamelan inspired pieces can be found at https://www.icme.jp/jd/en07/kodomono_sakuhin.mp4 (Tsubonou, 2020).

Case 3. The final case features a concert designed by Professor Yukiko Tsubonou. The concert was held at Tokyo University and the participants created all of the music by working in small groups. Musical styles included gamelan, the folk music of Nepal, Japanese traditional folk tunes, and many other musical genres and styles. Some composers participated by using musical instruments of East and West, and some even used less formal instruments such as a whistle. The concert was held on January 6, 2020, at Tokyo University, and it was designed with the following theme: Everyone Can Create Music. The following is an excerpt of Professor Tsubonou’s remarks:

In Japan, creative music making has been incorporated into the Course of Study, revised in 2008, and is now being implemented in schools as an activity that allows anyone to be creatively involved in music even if they do not have the skills to read music or play musical instruments. I believe that the aims of creative music-making are to foster creativity, to develop communication skills—because the focus is on making music in groups—and to acquire a broad musical perspective.

This lesson targets not only students who have various musical backgrounds and those who have been engaged in musical activities in various ways but also students who have been looking for something new and have never been involved in musical activities until now. Therefore, I designed and conducted every workshop keeping in mind that all of them could participate using their feelings and creativity. Taking up classical, jazz, pop, ethnic music from around the world, and contemporary music as materials, each student made their own music, especially focusing on the rhythm and scale of the genre of music selected for them while experiencing the commonality and uniqueness of them.

We performed an improvisational activity called “Musical Game” almost every session using clapping and other sounds produced around us. The creativity of the students was first reflected in this musical game and led to the next music-making experience. Many students slightly deviated from the set of rules of the musical games and quickly created their own “world.”

The design of this open studio differs from that of a normal music or lecture room: it has a big partition and thick pillars; some desks and chairs are arranged irregularly; and the seats are facing different directions. At first, I thought it would be difficult for everyone to make music in this studio while participating with each other, but each person was actually able to participate in making music after choosing a preferred location, facing a desired direction, and measuring an appropriate distance from me.

It seems that the freedom given to choose their position shaped the unconstrained atmosphere of the whole workshop.

The last lesson included holding a concert involving all participants while gradually expanding their “musical worlds” through these workshops. I think they enj oyed making music together to the fullest and that their seriousness and passion, as well as their creativity, gave rise to a power that overwhelmed me.

References: Amabile, T. (1996). Creativity in context: Social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

Ames. R. T., & Rosemont, Jr. H. (1998). The analects of Confucius: A philosophical translation. Random House.

Burnard, P. (2012). Musical creativities in practice. Oxford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper and Row. Ikuta, K. (2007). Waza kara shiru. Tokyo University Press.

Ikuta, K. (2011). Wazagengo. Keio University Press.

Ishigami, N. (2018). Fostering children’s musical creativity based on a simple rhythm pattern. International Journal of Creativity in Music Education, 6, 11-23. Institute of Creativity in Music Education.

Jackson, S. A. & Marsh, H. W. (1996). Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The flow state scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18, 17-35. Koyasu, N. (2010). Shisoshika-gayomu rongo. Iwanami.

Kozbelt, A., Beghetto, R., & Runco, M. A. (2010) Theories of creativity. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity. 20-47. Cambridge University Press.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 169;