Schooling in Uganda. Music as a Compulsory Subject

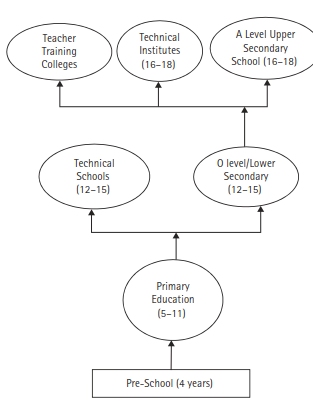

Figure 39.1 represents the structure of Uganda’s education system for learners between the ages of 3 and 18. In the urban centers, students learn music within the formal school context. Children in formal school settings often struggle with concentration. As they are naturally inclined to explore and practice mimicry, they learn best through play. Thus, approaches and methods that favor play are common in Ugandan formal school contexts.

Figure 39.1. Structure of Uganda’s education system for learners aged 3–18

The main challenge in these schools has been the use of tribal languages for instruction. The choice of language used in facilitating activities, as well as in the general teaching and learning, should ensure a commonality between learners. Yet, rural music teachers often use their tribal language to lead instruction in a formal class setting comprised of many tribes. As Borko and Putman (1997) have noted, instructional language must be considered within the context of teaching and learning if education is to be successful.

In the lower levels of schooling, music teaching is led by the classroom teacher rather than a music specialist. This is different from the high school where specialists are charged with the role of teaching and developing the music program. The curriculum established for all levels of music education is composed of generalized statements which educators are free to interpret. As such, there are many different views and opinions on how music composition should be taught in schools.

With a scarcity of well-prepared music teachers, opportunities to compose music often focus on lyrical composition. Learners at primary level schools are encouraged to communicate messages through singing “own-composed” songs. These often include repeated patterns, short phrases, or even rhymes. As time goes on, students interact with forms of notation. Music is not considered a core subject, thus there are limited resources for learners at institutions where music is treated as an extracurricular activity.

Music as a Compulsory Subject.In 2000, the government of Uganda, through its Ministry of Education and Sports, declared music a compulsory subject to be taught by all primary schools (Uganda, 2000). The resulting music curriculum stresses examinations of the final product rather than the practical processes through which learners derive the product. Classroom teachers at lower levels of schooling are not enthusiastic about teaching music, and those that are keen use varying and uncoordinated methods and approaches of inculcating music creativity. As a result, music creativity and indeed music composition are yet to take root in schools across the country.

One would think that music composition might be enriched through the variety of ideas, methods, and approaches teachers employ, yet instruction remains a significant challenge. The divergent opinions and ideas pursued by educators detract from the goal of well synchronized and standardized modes of assessment and evaluation as are needed for the ordinary and advanced levels of examination administered by the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB). As teachers train students to pass examinations rather than acquire sustainable creative skills, it is fair to say that the educational and creative skills that learners out to gain through school education are not prioritized in practice.

Though the current curriculum is a tremendous improvement over its previous iteration, it needs to be executed with caution to realize its intended outputs. Much of the formal music education presented in the school curriculum is Western in nature, structure, content, and design. The propagation of this Western-based curricula and traditions, in Uganda and indeed the whole of Africa, has been advanced for years while various scholars on the African continent have noted with concern the need to develop a pedagogical approach that reflects the compositional realities of African cultural practices. As Idolor (2005) points out, “The music curricula must be based on Africa sensitive music theory and practice” (pp. 87). Similarly, Masoga (2003) asserts that “it is wise to start with knowledge about the local area which students are familiar with and then gradually move to the knowledge about regional, national and global environments” (pp. 48).

An Evolving Mission.With the guidance and facilitation of the Ministry of Education and Sports, music educators across Uganda have worked through a series of mission, vision, and guiding statements concerning what music education, including music composition, should look like in schools. They have proposed and withdrawn multitudes of ways of teaching music composition in an effort to equip learners with skills for the challenges ahead. Despite all the time and effort put into the search for an appropriate pedagogy, the combination of the formal school environment, methods, and instructional strategies isolates learners from their musical cultures, traditions, and norms.

The frustration and feeling of inadequacy experienced by music teachers is balanced by learners who are naturally and inherently musical. This makes teaching somewhat easier for music educators who are continuously searching for ways to tap into learners’ inherent reservoirs of enthusiasm. However, teaching which leans strongly toward Western strategies has led to reliance on staff notation as the sole method of documenting music composition. According to Kigozi (2016), “The rationale for the music syllabus focuses on Western strategies rather than a true African context that reflects appropriate philosophical models that fit in an African context” (p. 12). Music composition sessions are seen as avenues for students to experiment with Western musical instruments, especially recorders in schools that can afford them, creating a sense of cultural isolation in learners experiencing and absorbing an explicit bias.

Curricular Reform.In 1999 the Ministry of Education and Sports, working through the National Curriculum Development Centre, reviewed the curriculum of Uganda. The work was guided and inspired by 1) the report of the education policy review commission entitled Education for National Integration and Reform (Uganda, 1989); 2) the government’s White Paper on Education (Uganda, 1992) addressing the recommendations in the report, and 3) the report of the curriculum review task force issued by the Ministry of Education and Sports (Uganda, 1993). The resulting curriculum became effective in January 2000 in all schools operating under the Uganda formal education system.

Unlike the previous curriculum, the new school curriculum of performing arts and physical education was designed to address the broader aims and objectives of education as stated in Article 13 of the Education Policy Review Commission’s 1989 report and in the 1992 White Paper on Education. Specifically, the following goals were identified:

a) to develop cultural, moral and spiritual values of life, (Uganda, 2000).

b) to promote understanding and appreciation of the value of national unity, patriotism and cultural heritage, with due consideration of international relations and beneficial interdependence, and

c) to inculcate moral, ethical and spiritual values in the individual to develop selfdiscipline, integrity, tolerance, and human fellowship.

The new curriculum merges the performing arts, including music under which music composition, dance, and drama, are taught, with physical education. By merging the performing arts and physical education, it was hoped that greater integration would occur. This merger however falls short of attaining the African philosophy that fits Uganda as a nation. The disadvantages of merging the performing arts with physical education are echoed by Reimer who asserts that policy-makers should avoid:

- Submerging the character of each individual art by focusing exclusively on family likeness rather than compatibility,

- Assuming that surface similarities among the arts show up underlying unities when in fact they usually do not,

- Neglecting specific perception reaction experiences in favor of a generalized, disembodied “appreciation of the arts," and

- Using non-artistic principles to organize the program to give an impression of unity. (Reimer, 1989, p. 230)

Some music teachers have advocated for the inclusion of both the African/oral and Western approaches in the same curricula. However, it does seem academically futile to subject both approaches to the same system of education, as the two are difficult to combine. While formal music education is easily standardized, oral traditions and expressions are typically passed on by word of mouth which usually entails variation, in lesser or greater degree. The enactment involves a combination differing from genre to genre, from context to context and from performer to performer; of reproduction, improvisation and creation. This combination renders oral traditions and expressions particularly vibrant and attractive. (UNESCO, 2006)

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 234;