Examples from Practice. The Rhizomatic Approach

In this section I briefly describe two approaches to music composition developed by myself in music classrooms and workshops with children. I do so to illustrate some of the practices that have been taking place in Portuguese music classrooms, knowing that I do not exist in isolation, and that my work reflects my entire learning journey as a music education teacher and researcher. Thus, what I report now is a mirror of my own teacher education in the university, the many conversations I had with other teachers, researchers, and musicians, all that I have learned while attending and presenting in conferences or seminars, and, of course, what I have also learned while writing and reflecting about these matters, through the lenses of the many actors that have participated in these projects.

The definition of the two approaches to music composition is a result of the analysis of some of the main creative projects I have developed with children as a teacher and researcher, from 2005 to the present moment. During this period of time, that includes my graduation in music education4 and my PhD in music5 (pedagogy), and that was of paramount importance in my professional life, I developed a perspective on music composition as a social practice, profoundly embedded in pupils’ cultures and living contexts, much in the sense of what is presented during the first section of the chapter (Barrett, 2003 and 2011; Kaschub & Smith, 2009 and 2013; Veloso, 2017; Veloso & Mota, 2021).

Thus, in my classroom, I always tried to implement activities and projects that valued children’s interests and backgrounds. This was especially true when approaching music composition activities, as I always tried to encouraged pupils to develop their musical pieces and songs from their lived experiences, from their thoughts and feelings, and from their views and reflections about the world. This approach to teaching and learning music was supported not only by the literature I had studied and the practices I had observed since my graduation in music education, but also by the legal normative that invigorated at that time—the NCBE (2001). The NCBE was published during my first college year and had an enormous influence in my practice as a teacher and research.

In fact, I found in the NCBE the legal fundaments to develop a music education practice based on the theoretical and philosophical perspectives that were at the center of my education. This allowed me to develop, in congruence with my own ideas and beliefs, an inclusive and democratic music education practice, based on children’s specific contexts of living and ways of relating to sound and music, emphasizing pupils’ agency, creativity, and imaginative action.

I have picked one example from each approach, that I present now as an illustration of similar projects developed in music classes and workshops with children from six to 11 years old. This means that the examples that I outline next refer to the first and second cycle of education (primary school and first years of middle school) that are, as we have seen before, the years in which music education is a compulsory subject of the Portuguese school curriculum.

The Rhizomatic Approach.In biological terms, the rhizome is an underground root system that grows horizontally and outward, the way and ginger roots. In this sense, it is in opposition to arbor roots that give birth to trees that grow vertically and upward. Translating this into a philosophical field, Semetsky (2008) notes that the rhizome is a nonhierarchical system with no beginning or end, that spreads through “movements in diverse directions instead of a single path, multiplying its own lines and establishing the plurality of unpredictable connections” (p. xv).

If we think about music education and music composition from the perspective of the rhizome, we are faced with a structure that metaphorically allows pupils to grow and develop pathways in new and unexpected ways, through diverse “lines of flight” or “creative musical routes” that they trace while creating meaning to their lived experiences (Lines, 2013 Schmidt, 2012). Acknowledging music composition from this point of view means recognizing children’s’ interests and past experiences, emphasizing that there are many and diverse paths that pupils might take during their creative voyages—paths that are distinguished by their uniqueness and that are, as Margaret Barrett (2003) would put it, related to the specific relationships each child establishes with the available tools and resources while she is composing, the music that is being created, and those that might take an important part in this process (her peers, teachers, parents). Furthermore, it is an approach that strongly depends on the specific motivations, actions, and initiatives taken by each pupil, and that needs, therefore, a classroom environment where children feel safe and encouraged to manifest and express their feelings, thoughts, ideas, or desires.

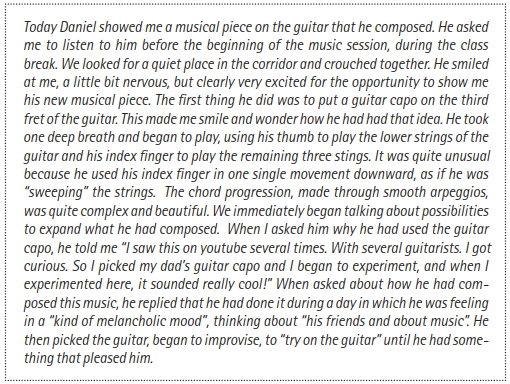

Figure 40.2 shows an excerpt taken from my field notes, written after a session of a music workshop implemented from 2015 to 2017 in a Portuguese state school (Veloso & Mota, 2021). This workshop was developed in a classroom context, with pupils aged between nine and eleven years old, during two academic years—encompassing pupils’ last year of primary school and the first year of middle school. The workshop, which occurred once a week for an hour and a half, as another activity of the curriculum, was developed as a follow-up of a case study already documented elsewhere (Veloso, Ferreira, & Bessa, 2019). Throughout the workshop, pupils developed several interdisciplinary activities and projects through differentiated pathways, in a creative, informal, and collaborative approach to music-making.

Figure 40.2. Field notes, November 2016

They had several musical instruments at hand, that included not only the Orff ensemble but also guitars, bass guitars, drums, keyboards and other handmade invented sounding objects and instruments. I acted both as a researcher and facilitator, guiding students in specific tasks, suggesting tools and ways for developing the work, giving cues in specific ways to approach musical instruments, always valuing pupils’ specific musical backgrounds and interests. As part of the workshop, pupils gave several concerts to the school community, organizing also open rehearsals and performing at other school events such as exhibitions or seminars.

Daniel, a 10-year-old boy who loved to play the guitar, composed this particular piece of music following his ear, his intuition, what he was feeling. He was neither concerned about any specific task given to him in the classroom, nor about the “correct ways” of making music or playing guitar. He was concerned with the music, the overall sound and what he was expressing through it. His approach to music composition was one of trial and error, involving multiple attempts, and, as he explained later, multiple moments of experimentation where he tried out his ideas “once and again, playing, listening, playing again, organizing and putting the sounds together,” until he finally felt he had something he enjoyed and wanted to share with other persons. After this moment, I encouraged Daniel to present his musical piece to his peers. Not only did he do that with great confidence and joy, but he also talked about other musical instruments he would like to put together with the guitar, inviting some of his colleagues to join him. Together, and for a period of three weeks (three music sessions), the group created a new musical piece that evolved from Daniel’s first ideas.

During this period, they rehearsed by themselves in a different room while I was working with the rest of the class. From time to time, they invited me to join them, to share my thoughts about what they had done so far, asking questions, and exposing their views and ideas. In the end of the academic year, they proudly presented their musical piece in a concert organized to all the school community. I remember they were so proud.

Daniel was the first pupil from his class to approach music composition in this way, but many others followed him. Experimenting on guitars, percussive sounding objects, invented musical instruments, or using their own voices, many pupils began to present, on a regular basis, their own musics: Original compositions, arrangements of other songs, small ideas that they didn’t know yet how to develop and expand, each child bringing a new and fresh manner of picking sounds and organizing them, each one of them designing a unique path in their journey within music composition.

Embodying the metaphor of the rhizome, pupils traced multiple and divergent routes in a horizontal and non-hierarchical process. I believe that, in this way, music composition grew into a powerful means of communication through which pupils could express their thoughts and feelings, envisaging music as a place where there are no dichotomies regarding good or bad and where each one of them could embrace her/ his own individual and unique path. Thus, we might perhaps say that, when conceived “rhizomatically,” music composition projects might be understood as journeys with diverse points of departure and different points of arrival, where pupils are not afraid to take risks, to experiment, to listen, to play, and to try once and again, communicating their ideas in creative and, quite often, surprising ways.

The Thematic Approach.In the thematic approach, I usually invite children to create their music departing from other media, mostly from the artistic realm. I might use a painting, a film, a story, a poem. This object/idea is what Acaso y Megias (2017) named as “detonante,” a “spark” that helps children to travel along new imaginary landscapes, and through which they connect (in the specific case of music education) a set of ideas with musical material.

The “spark” is used, therefore, to stimulate children’s’ curiosity and, as a followup, emotions such as surprise or wonder. This approach to music composition is in line with recent findings on the fields on neurobiology and arts education that have shown consistently that such emotions have a decisive role in fostering our attention and our desire to think and reflect, and are, thus, essential to learning and to the development of creative activities (Damasio, 2000 and 2001; Teruel, 2013; Piersol, 2014; Veloso, 2017; Veloso, 2020). Motivated by strong feelings of surprise and wonder, pupils direct their attention and thinking processes toward what is being explored.

This is the beginning of creativity and transformation. Slowly, they engage in a process led by their imagination, connecting different symbolic worlds, transforming their thoughts, ideas, and images into sounds and music. At the same time, and much in line with what I previously mention about the importance of pupils’ personal and social backgrounds (Bruner, 1986, 1990, and 1996; Vygotski, 2007), in this approach, the “spark” typically emerges from ideas or themes that are significant for children’s’ lives. Ideas that evoke their interests and preoccupations, and that, many times, relate to sensitive issues such as difficult familiar relationships, discrimination, gender issues, or bullying. This practice is, in a sense, much aligned with the “political engaged music” (Mota, 2001, p. 152), mentioned in the “Brief Historical Overview” earlier in this chapter, as it tries to give voice to children’s thoughts and feelings without censure, bringing to the fore those issues that are part of children’s daily struggles when they try to cope with world.

An example of this approach is found in Project Bernardino, based on a book written by Manuela Bacelar. The project is designed for six-year-olds and was developed in a primary state school. Bernardino tells the story of a young lion that was quite different from all the other lions. Bernardino was vegetarian. This was the cause of great sadness and concern to his father, who could not understand his son’s way of living. Sad and lonely, Bernardino ran away from home. Throughout his journey he met many friends, and one of these friends taught him how to play the flute. Bernardino was a good student, learning fast and becoming a great musician that toured around the world. One day he came back home to see his father. And although his father was still concerned about his son’s choices in life, in the end Bernardino conquered his heart with the music he created.

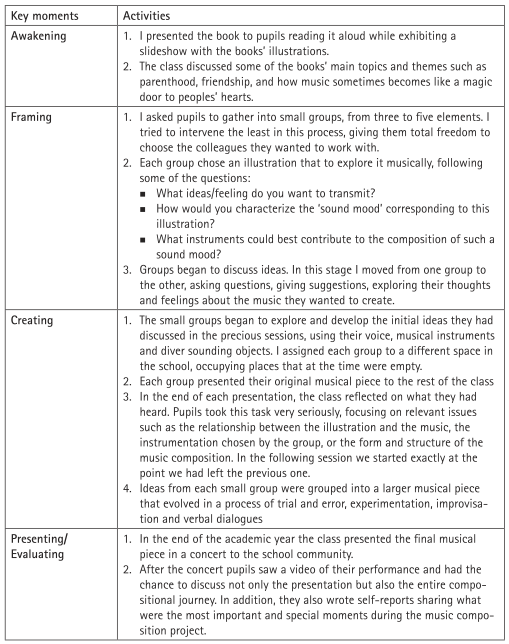

The story and the many themes that emerged from it—especially related with difficult familiar relationships—were the detonante, the “spark” given to pupils to begin their creative process. The idea of using Bernardino as a detonante came about because this book was part of pupils’ reading list on their general class, and their primary teacher thought it could be a good idea to introduce the book by relating the words and illustrations with music. When she talked to me about this, it made perfect sense, and we both decided to develop the project together. Our intention was that pupils could have an opportunity to reflect on the ideas evoked by the life of this young lion, his relation to his father, to his friends, and to music. The project was developed in four key moments, as shown in Figure 40.3.

Figure 40.3. Project Bernardino—key moments

Pupils participated in this project with great enthusiasm, connecting the book’s story with their specific life experiences, and using them as a base for the development of musical ideas. They established a truly strong emotional connection with the story and were, therefore, quite motivated to engage in all the tasks involved in the project.

The final concert mentioned in last phase of the project (Figure 40.3) was organized by teachers, parents, pupils, and other school workers. Everybody participated enthusiastically, working in close collaboration. In the day of the concert the pupils seemed extremely excited. However, this doesn’t seem to have had a negative influence on their performance. On the contrary. When their time arrived, they stepped into the stage smiling and happy, but deeply concentrated. The performance was a very beautiful moment that the audience deeply appreciated, something that was visible in the end of the concert, in their joyful gestures and words.

Later, after watching the video of their performance, when discussing and reflecting on the process they focused specially on two issues: First, the possibility to experiment and interact with musical instruments from the very beginning. Pupils clearly stressed that this had been of paramount importance in their journey. Many stated they felt like “real musicians," when experimenting or improvising with the available musical instruments and sounding objects. The second issue that was mentioned, was the importance of working in groups. Pupils clearly looked at the group as an essential part of the venture, developing a strong emotional attachment and sense of belonging toward their peers. Moreover, they mentioned frequently how the group opened their own imagination to other musical possibilities, highlighting how the collaborative work became a means to do better, to work harder, and to develop ideas that, otherwise, would never exist.

The thematic approach is neither better nor worse than the rhizomatic approach. It is different, as, at least in the beginning, pupils’ ideas depart from something that is presented and chosen by the teacher, and by the questions/suggestions that guide the transition from the detonantes to the music. However, this presentation is only an invitation, a platform for pupils to begin thinking creatively through sounds. Therefore, in this approach it is also of extreme importance that pupils might have the opportunity to work on their own, to express and discuss their ideas with their peers, to experiment once and again without fear of doing “the wrong thing" The job of the teacher is to guide, to ask questions and pose new challenges, listening carefully, and creating a classroom environment that might offer the conditions to a genuine and creative dialogue.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 237;