Music Education and Music Composition in the General School Curricula

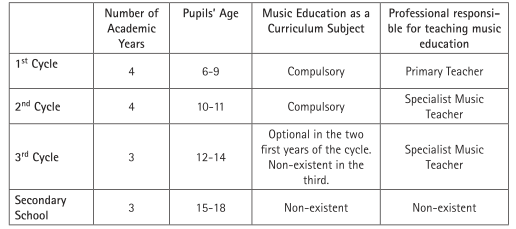

Presently, compulsory education in Portugal is divided into four learning cycles. The first three cycles are part of what is named as “Basic Education,” and the last cycle as “Secondary Education.” As shown in Figure 40.1, music education is a compulsory subject only in the first and second cycles of education.

This was not always the case, since the first major change in school education in Portugal occurred as a result of the national reform of the educational system and the publication of the Basic Law of the Educational System, in 1986. This law not only defined the third cycle of education as the level of compulsory education, as it transformed music education into a mandatory subject of the curriculum.

Figure 40.1. Music education during compulsory schooling

The law also pronounced the formulation of a new curricula for teacher education, disclosing further the highly innovative idea of the possibility for primary teachers to work collaboratively with a specialized teacher in the school subjects related to the arts (Boal-Palheiros, 1993; Mota, 2007). However, the various governments that led the country following the publication of this law were somehow negligent toward art education, addressing it—even in the 21st century, as we will see later in more detail—into an isolated, remote space in the curricula, highlighting, at the same time, those areas related to logical-mathematical thinking such as mathematics, science, or languages.

This was a period of heated debates among music education teachers and scholars as they discussed different perspectives and points of view on what should be prioritized in the practice of music education and consequently, in the education of teacher- students respecting this specific knowledge area. These debates were based essentially on the ideas of innovative contemporary educators and researchers, especially Anglo- Americans (Mota, 2014), that gave a fundamental contribution to the construction of what should be an inclusive, democratic, and participatory music education.

The First Cycle of Education.During the first cycle of education, music education is a compulsory subject of the curriculum as part of a block of five hours of artistic education, and should be taught by primary teachers. However, many primary educators—as it has been documented all over the Western world—do not feel confident about teaching music (Economidou Stavrou, 2013; Hogenes, Oers, & Diesktra, 2014; Mota, 2007, 2014; Shouldice, 2014; Veloso, Ferreira, & Bessa, 2019), arguing that their teacher training didn’t give them sufficient preparation in what regards music teaching and learning. Thus, feeling unprepared to develop a music education curriculum in their classes, these teachers are often afraid to move much beyond the teaching of simple songs, the development of movement activities and, sometimes, the introduction of very simple tasks that involve the use of musical instruments.

To overcome this gap, and following a philosophy based on a “full-time school” maxim, in 2006 the Ministry of Education launched a program that consisted of “10 weekly hours of extracurricular activities (English, music, sports) taught by specialist teachers, that children attended on a voluntary basis” (Boal-Palheiros & Encarna^ao, 2008, p. 98). A music syllabus was created with specific guidelines intended to help teachers to develop their work. The Portuguese Ministry of Education entitled these activities “Curriculum Enrichment Activities” (CEA). And although, at least in in principle, this program did not remove the mandatory teaching of music education within the curriculum, the implementation of these activities has been the cause of strong ambiguities, as there is repetition of music in both curricula (Araujo & Veloso, 2016; Mota, 2007, 2014) and some ambiguity regarding who is truly responsible to teach music education in primary schools.

Moreover, in addition to the implementation of these activities, there was also a setback in terms of the professional qualifications required to teach music within this program. In fact, and although it was initially claimed that to teach music, a graduation on music education was necessary, in practice, the music classes have often been taught by young persons who have only attended a basic or secondary school degree in music at the conservatory or at a music academy. In both cases, music composition activities are almost nonexistent. Even when we talk about CEA, where teachers have at least some music training, it is rare for teachers to feel comfortable enough to develop music composition activities and projects. In fact, and similarly to what happens to music specialist throughout the several years of general school in some European countries and the United States (Boal-Palheiros & Boia, 2017; Klader & Lee, 2019; Stringham, 2016), they prefer to focus their practice on vocal and instrumental performance or on a more theoretical approach to music education.

Graca Mota (2007), outlining some concerns about the implementation of music as an enrichment activity, explained that with the new program, music education could be discarded from the elementary curriculum in some schools. Pupils not attending afterschool enrichment activities could be in danger of not receiving any music education. As a possible solution, Gra^a Mota (2007) advocated for a collaborative work between the primary teacher and a music specialist—that was, as we have already seen, predicted in the Basic Law of the Educational System. This collaborative work could be done through the implementation of projects that, on the one hand, would have their focus on making music, through performance, composition, or audition, and, on the other hand, would embrace a real interdisciplinary process relating music with other arts and also with other curriculum subjects.

However, until now, this has not become general practice; pupils receive music education in primary schools within the voluntary “curricular enrichment activities,” while provision of musical activities in school hours depends solely on the particular primary teacher. Notwithstanding, there is an exception to this generalized practice. In the Madeira Island—that has political autonomy regarding the implementation of the curriculum—the current education model in primary schools is similar to the one advocated by Gra^a Mota (2007). In fact, in Madeira, children attending primary school have music classes with a specialist music teacher during curricular hours. However, a recent three-year case study developed by CIPEM3 about music education in the Madeira Island’s in primary schools, shows that musical activities in these schools also focus mainly on vocal and instrumental performance and that music composition is, once again, almost absent from the activities and projects planned and implemented in the classroom (Mota & Abreu, 2014; Mota & Araujo).

The Second Cycle of Education.In the second cycle of education the curriculum that prevails nowadays was inspired in the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (MMCP), organized through a spiral around five main concepts: timbre, dynamics, pitch, rhythm, form. This syllabus was published in 1991 by a scientific committee that worked on the basis of an epistemological ground that highlighted the conceptual development theorized by scholars such as Jerome Bruner (1977).

It was the first time that Portugal had a music education program based on a logic of musical development and that offered an innovative way to teach and learn music. This educational program intended to move away from some retrograde practices, to bring contemporary music into the classroom and to help pupils to achieve a conceptual understanding of music through exploration and experimentation. However, the Ministry of Education misunderstood the guidelines given by this committee, transforming what was a spiral in a closed grid. Thus, many music teachers began using music to exemplify the meaning of concepts, or to “test” students regarding those concepts. It also led to an emphasis on music theory, rather than on making music.

Despite this difficulty, and as mentioned before, at the end of the 20th century a rich discussion arose in Portugal, concerning what should be the priorities for a music education practice that was intended to focus on meaningful musical activities, and informed by values such as inclusion, pedagogical differentiation, and the active participation of pupils.

One of the theorists that influenced this discussion was Keith Swanwick, who proposed a model of musical development based on the analysis of children’s music compositions (Swanwick & Tillman, 1986; Swanwick, 1988). This analysis stood, at the same time, for a curriculum centered on music-making, and where composition, alongside performance and music listening, could be ensured a relevant place (Swanwick, 1979)- F°r the author, composition was central to music learning and should be understood from a global perspective:

Under this heading is included all forms of musical invention, not merely works that are written down in any form of notation. Improvisation is, after all, a form of composition without the burden or the possibilities of notation. Composition is the act of making a musical object by assembling sound materials in an expressive way. There may or may not be experimentation with sounds as such. A composer may know what the materials will sound like from past experience in the idiom. Whatever form it may take, the prime value of composition in music education is not that we may produce more composers, but in the insight that may be gained by relating to music in this particular and very direct manner. (1979, p. 43)

This approach to music composition and its contextualization in what Keith Swanwick named as “The Comprehensive Model for Musical Experience” had strong repercussions on the panorama of music education classes regarding musical creativity and specific music composition projects. In this particular aspect, it seems fair to say that Swanwick was, therefore, a fundamental scholar in the introduction of music composition in music education classes in Portugal. In fact, with this new theoretical lens it became clear that it was of crucial importance to offer opportunities to children where they had the chance to express themselves musically through the creative manipulation of musical material.

Another essential milestone in the development of music composition in the classroom is directly related to the work developed by educators/composers such as Brian Dennis (1975), Murray Schafer (1976), and John Paynter (Paynter & Aston, 1970). These authors stood fiercely for a music education in which creativity occupied a broad and significant space in children’s musical experiences. John Paynter and Peter Aston, in their book Sound and silence (1970), refer to making music as a response to life and the world around us. Being an art, as the authors continue to explain, this response is creative, allowing children to express thoughts and feelings through the medium of sounds, using their imagination. Paynter and Aston developed a music education philosophy based on the active exploration of sounding objects and musical instruments by the pupils, the use of techniques similar to those adopted by contemporary composers and a vision of the teacher as a guide and facilitator.

These educators/composers were part of the so-called creative music movement in the 1960s and 1970s. This movement included several musicians and educators who sought to introduce in the classroom a more open and comprehensive view on music composition that could go beyond the tonal paradigm and include in its practice the entire sound palette that surrounds us. At the same time, it is a perspective developed through a new epistemology based on “a plurality of knowledge forms, the recognition that there were different ways of knowing, different ways of making meaning and significance, different kinds of truth” (Finney, 2011, p. 18).

Paynter visited Portugal more than once, invited by APEM. During his visits he gave seminars, workshops, sharing his philosophy and encouraging teachers to plan and implement creative projects and activities in the classroom. This had a significant influence in the development of music composition in Portuguese classrooms, as teachers that participated in these workshops responded with high levels of enthusiasm. These teachers also developed a strong sense of commitment toward the inclusion of creative practices in their classrooms, planning and implementing ideas that were either acquired in the workshops, or developed afterward, when reading these authors’ books or sharing ideas with other colleagues. However, in practical terms, the creative music movement had no enduring influences in Portugal. Although important, the work developed though these workshops and the discussions and transformations they initiated were not systematically developed in a way that could significantly influence the education and work of most music education teachers.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 237;