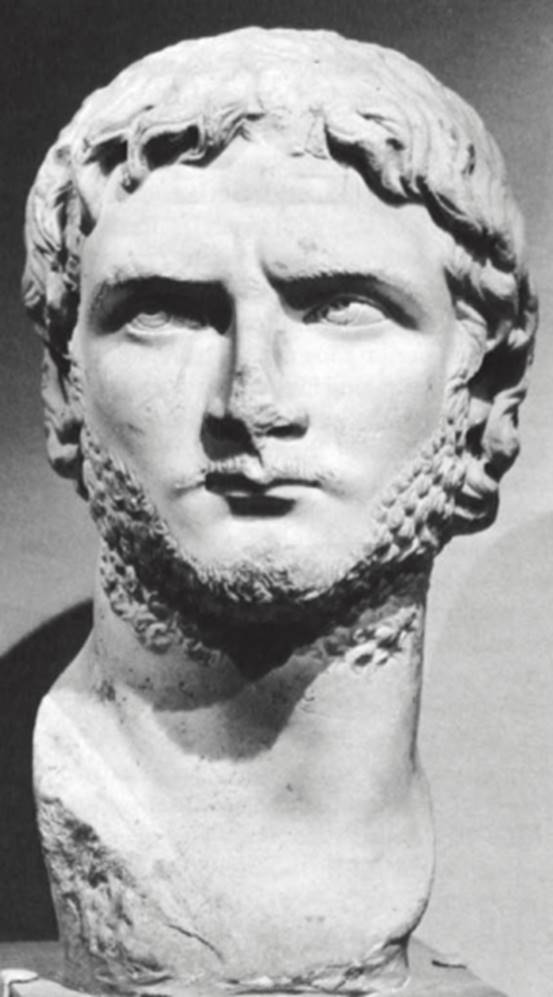

Head of Gallienus. Rome, about 262. Greek marble

This fine portrait of the emperor Publius Egnatius Gallienus must have been inserted into a draped bust or statue, for remains of a drapery fold can be seen over the right shoulder. The point of the nose and ends of the frontal curls are missing, as well as a small section at the right edge of the bust piece. The surface is damaged in places, but the ancient polish can still be observed on the cheeks and around the eyes.

The likeness may be closely compared to that portrayed on a medallion struck in Rome in 262, the year of the emperor's decennalia (Delbrueck, 1940, pi. 16, fig. 62) and on medallions issued in 267 (Delbrueck, 1940, pi. 17, fig. 76). In both medallions and sculpture appear the idiosyncratic features of the emperor: the square head, pursed mouth with protruding upper lip, small eyes framed by wide brows, low cheek bones, and full chin. These medallion portraits also show in profile the same scattered, pointed locks over the forehead and the short, elegantly curled beard which clings around the upper neck. An intensity of expression is conveyed through the staring eyes, which here are directed slightly upward. It is a widely held, and probably correct, hypothesis that the medallion artists and sculptors were working from a common sculptural prototype.

The overall plastic rendering is reminiscent of classical portraiture, and thus the term “renaissance" is commonly applied to Gallienic art. The classicizing tradition, however, is only one in a complex of layers of stylistic traditions, and the total impact of this head is actually strongly anticlassical. The compact, massive shape dominates and not even the ears are allowed to protrude from the controlling abstract form. The individual features are not organically related as in classical portraiture but are isolated by the broad flattened planes of the face. Moreover, the uneasy tension conveyed by the upward stare and the asymmetrical contortion of the brows reflect a new spiritual consciousness, an emphasis also found in the contemporary Neoplatonic philosophy of Plotinus, who we know from ancient accounts enjoyed the patronage of Gallienus and his empress Salonina.

Gallienus may also have intended further symbolic meaning. 1/Orange (1947, pp. 86-90) first noted the reference to Alexander the Great on a medallion of Gallienus of 260 (Delbrueck, 1940, pi. 15, fig. 45). The Museo Nazionale head appears to be a later variant of this portrait type, also represented by portraits in Lagos (Felletti Maj, 1958, no. 294), Brussels (Fittschen, 1969, p. 219, fig. 36) and the Museo Torlonia, Rome (Felletti Maj, 1958, no. 295). Through this portrait type Gallienus presented himself to the Roman people as a Savior-King in the Hellenistic tradition, deliberately allowing his own features, particularly the upward gaze and peculiar hairstyle, to be adopted to those of his model, Alexander, in his deified form. The controlling political theme behind this allusion as well as the others used in his varied portraiture was the promise of a new Golden Age (Hadzi, 1956).

Found in the House of the Vestals in the Roman Forum.

bibliography: Hadzi, 1956, pp. 46-48, 86-87, 185-190; Felletti Maj, 1958, no. 293; MacCoull, 1967-1968, p. 72, no. 4, pi. 22, fig. 4; Helbig, 1969, III, no. 2315 (H. von Heintze).

Date added: 2025-07-10; views: 229;