Portrait seal of a Gothic king. Western Empire (Rome ?), 2nd half 5th century. Amethyst

The gem portrays a frontal bust above a monogram —a man with large eyes, broad mouth, mustache but no beard, and heavy mass of hair combed downward from a center part to cover the ears. He wears Roman costume: tunic with toga over left shoulder. No Roman of this period wore hair of this length, mustache without beard, or earring such as appears over the right shoulder.

The subject belonged to one of the Germanic tribes settled within the Roman Empire between the fourth and sixth centuries. The size of the gem indicates it served in a finger ring; amethyst, like sapphire, was reserved for royal use. Other extant seal rings were made for Childeric I, a Frankish king who died in 481 (Schramm, 1954, pp. 213- 217), and Alaric II the Visigoth (484-507) (Schramm, 1954, pp. 217-219), but these seals are far cruder in execution, and on both of them the rulers' names are spelled out in full.

The monogram was deciphered by Berges (1954) as "Theodoric," and, since no adequate alternative reading has been offered, the seal is assumed to have been made for the well-known king of the Ostrogoths. Theodoric ruled Italy from 493-526 after receiving a prince's education in Constantinople. However, the only other image of Theodoric, on a unique gold medallion presumably struck on the occasion of his visit to Rome in 500, shows a very different figure from that on the seal. The coin portrait not only differs totally in style of execution, but also in the depiction of the coiffure, which falls more or less uniformly without a part—probably a Germanic fashion found on Constantinopolitan ivories of the early sixth century. The face on the coin is square-jawed, not triangular as on the gem. The only similarity is the mustache both wear. Sande (1975) has recently observed that if the medallion does represent Theodoric the Ostrogoth, the gem cannot portray the same man.

But the Ostrogothic king was not the only German ruler named Theodoric. The Visigoth Theodoric I died in victorious battle against Attila in 451, but his son Theodoric II ruled from 453 to 466, enjoying for the most part excellent relations with Rome from his base in southern Gaul. It may be worth noting that Sidonius Apollinaris, who lived at his court, remarked on Theodoric II's devotion to cultivating his mustache [Epist. 1.2.2—3).

The gem was probably cut by a Roman artisan as a gift to the barbarian chief; micro photography has revealed what appears to be an inscription, about inch long at the left edge of the gem, but, beyond the probable presence of an "o" and a "c" or "x", it seems indecipherable. It would be an artist's signature, if anything.

Bibliography: Berges, 1954; Schramm, 1954, pp. 219-222; Sande, 1975, p. 82 n. 7.

Ceremonial Obsession: Ritual, Power, and Christian Transformation in Late Antique Art & Society

If ceremony is the customary mechanism by which a structured society articulates its most vital features, then Late Antique society was most peculiarly addicted to the custom, even ritual, of ceremony. Previous Roman tradition had increasingly emphasized the ceremonial aspects of public life, formalizing the most varied social relationships; ceremony also found full expression in well-established motifs, presented repeatedly by works of art. This fixation on carefully staged ceremonies complemented the highly structured political and social system, dominated by an increasingly remote leadership and an extremely wealthy aristocracy—a hierarchical system largely formed by the still powerful models of Roman paganism and maintained by the notables who governed society and the state.

Such a society tended to abjure the validity of personal relationships, except at the highest levels, and to consider the mass of the citizenry irrelevant outside of the demands of politics. Yet, this attitude stood opposed to the teaching of primitive Christianity, wherein each person—estimable in himself and not to be measured by possessions or status— had direct access to the highest majesty of all—God. The complex institutional interaction between the aristocracy and the masses as the empire was Christianized is demonstrated in the slowly changing artistic representations of public ceremonies.

The appearance of magnificence seems to have been the touchstone of this society, perhaps in an effort to sublimate the growing unpleasantness of life. The semipermanence of late Roman sociopolitical institutions, subject to increasing stratification, assured the use of traditional imperial motifs, precisely because these motifs continued to be recognizable signs of present power and ancient splendor. In a world of declining physical resources, further weakened by a gradual alienation from Greco-Roman civilization, the illusion of institutional continuity seems to have been strengthened by the greater formalization of action through ritual. Every act of the emperor, members of his suite, and of the great aristocrats became transformed into a carefully staged scene, framed in such a way as to elevate the principal actor, or actors, into a position of eminence. If, in reality, matters were seldom so well defined, these powerful images at least projected a protective aura of security.

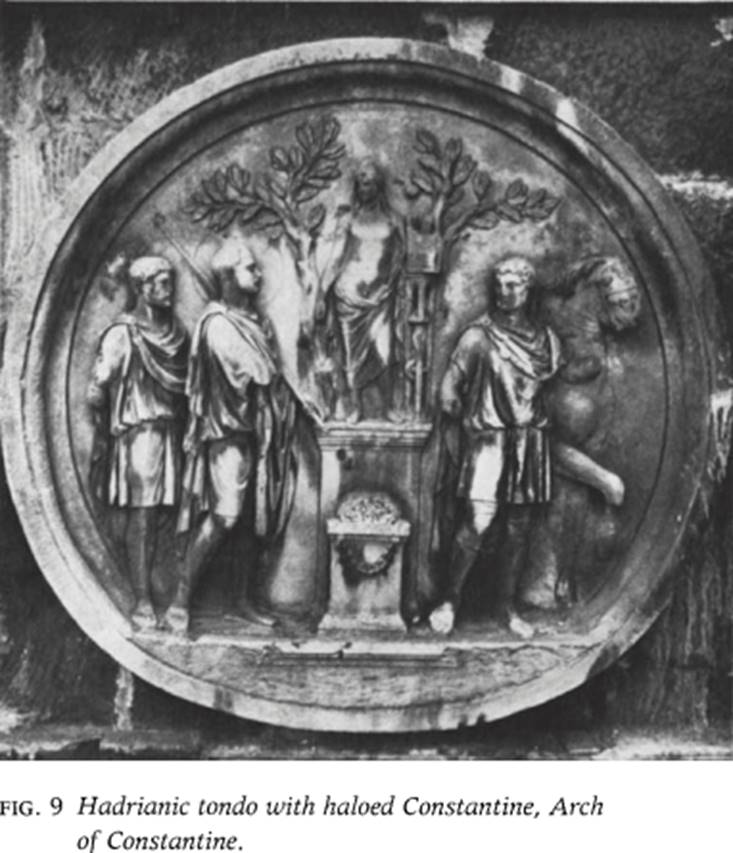

The traditional imperial ceremonies—triumph, investiture, formal address, advent, departure, sitting-in-state, death, and apotheosis—continued to dominate works of art commissioned by the state. These motifs, like the rhythmic acclamations that greeted the emperor whenever he performed some ceremonial action, were reinforced by repetition. Equestrian monuments continued to be raised in Rome and Constantinople (fig. 7); emperors made triumphant entries (fig. 8), spoke to their armies (no. 57), appeared in colossal forms, symptomatic of their power (nos. 11, 23), stood in sumptuous court dress whose splendor complemented their special nature (no. 65), wore haloes indicative of their superhuman, radiant authority (no. 67; fig. 9), and rose unto heaven in the uplifting ceremony of apotheosis (no. 60) when their time on earth was completed.

Fig. 7. Drawing of equestrian statue, Justinian or Theodosius. Budapest, Budapest University Library, cod. 35, fol. 144

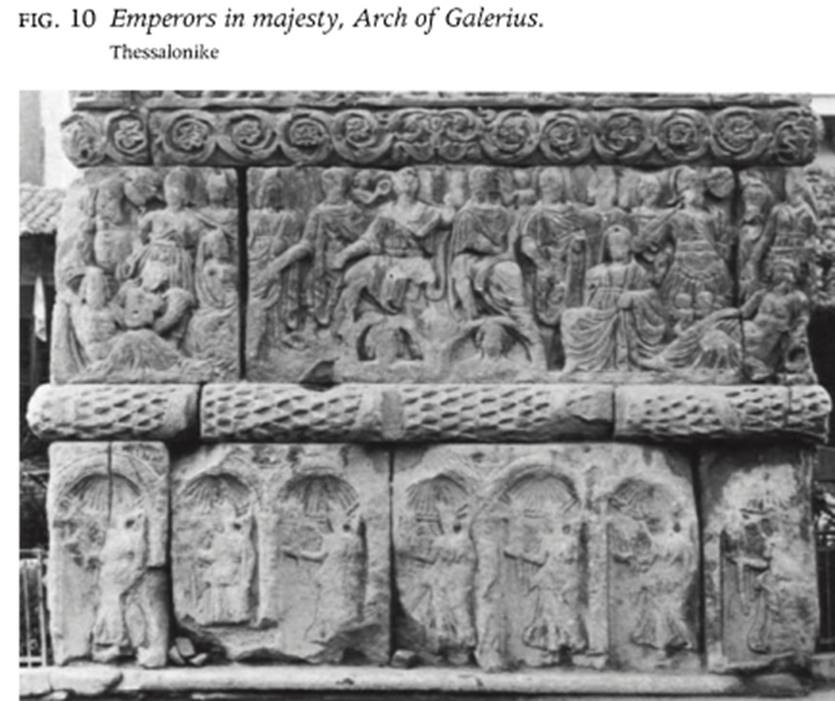

When seated in majesty surrounded by their temporal court (nos. 64, 65), sometimes augmented by celestial companions (fig. 10), the emperors assumed rigid, frontal positions as if they had been transmogrified into images of pure majesty. This is the deliberate posture of Constantius II, who thus presented himself in 357 to the people of Rome:

And as if he were planning to overawe the Euphrates with a show of arms, or the Rhine, while the standards preceded him on each side, he himself sat alone upon a golden car in the resplendent blaze of shimmering precious stones, whose mingled glitter seemed to form a sort of shifting light. And behind the manifold others that preceded him he was surrounded by dragons [the imperial standard], woven out of purple thread and bound to the golden and jewelled tops of spears, with wide mouths open to the breeze and hence hissing as if roused by anger, and leaving their tails winding in the wind. And there marched on either side twin lines of infantrymen with shields and crests gleaming with glittering rays, clad in shining mail.. . . Accordingly, being saluted as Augustus with favoring shouts, while hills and shores thundered out the roar, he never stirred, but showed himself as calm and as imperturbable as he was commonly seen in his provinces. For he both stooped when passing through lofty gates (although he was very short), and as if his neck were in a vice, he kept the gaze of his eyes straight ahead, and turned his face neither to right nor to left, but. . . neither did he nod when the wheel jolted nor was he ever seen to spit, or to wipe or rub his face or nose, or move his hands about (Ammianus Marcellinus History 16.10. 6-10 [Rolfe, 1950, pp. 245, 247])

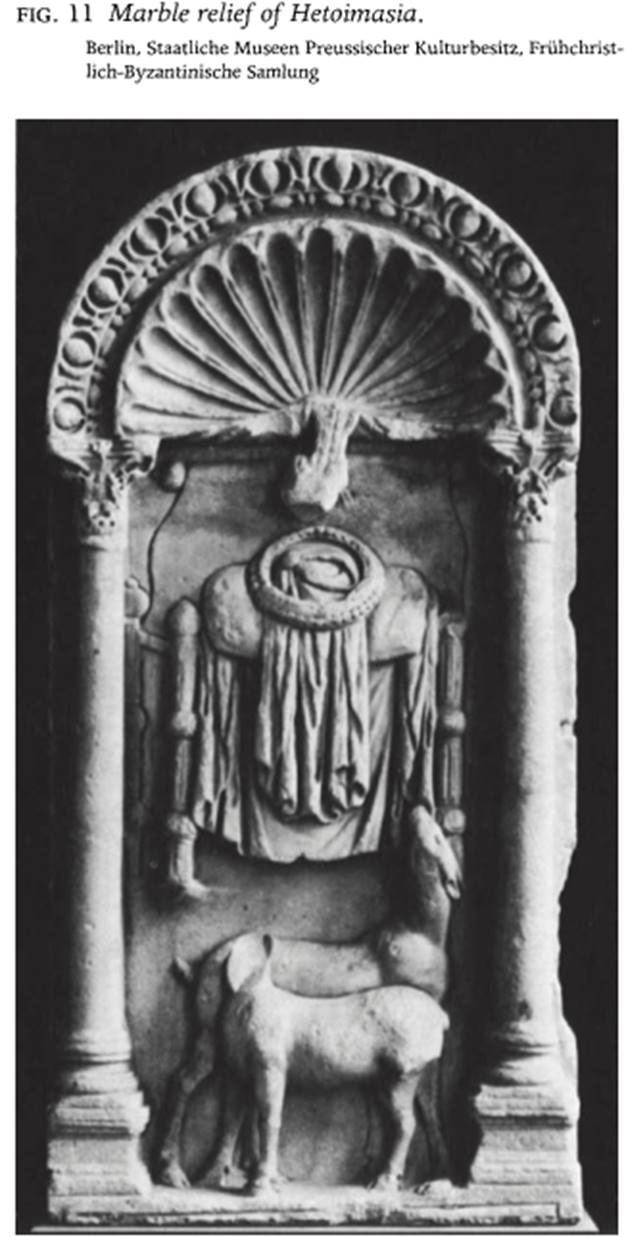

To emphasize the glorification, even transmutation, of the mortal ruler as a superhuman being, artists also came to rely heavily on symbols, like the halo or the arcuated lintel on the Missorium of Theodosius (no. 64; cf. no. 104, entrance of Diocletian's palace, Split), which indicated the epiphany of a majestic lord. Almost in anticipation of the medieval doctrine of the “king's two bodies," the image of the throne itself could stand for the emperor, often accompanied by the further regal attribute of the diadem. It is in this realm of symbols that Christianity makes its appearance with the translation to Christus Rex, as indicated in the mosaics from the Cathedral Baptistery, Ravenna, or in a recently discovered early Byzantine relief, now in Berlin (fig. 11). Where apotheosis could be applied to the heavenly translation of the prophet Elijah (no. 438), then the signs of divine favor which supported regal authority even as early as Augustus, the first emperor, took on a new meaning. Under the old Lex de Imperio the Roman people supposedly exercised the authority to elect an emperor and to bestow upon him their power over the state. Perhaps influenced by the biblical model of King David, the presence of God himself became evident as the manus dei in the dynastic investiture medallions of the House of Constantine (no. 62); the symbol itself of the hand of God was already used in the biblical context of the third-century paintings from the synagogue at Dura Europos (no. 341).

Christianizing intrusions into the traditional pagan repertory of Roman state monuments had previously occurred among the triumphal images of Constantine with varying degrees of explicitness. The phrase instinctu divinitatis in the inscription of Constantine's triumphal arch in Rome (no. 58) had two effects; it did not refer to the traditional gods, who were conspicuously absent from the arch because the usual representation of the triumphal procession to Jupiter Capitolinus was missing, and it did refer, apparently, to the Christian deity proclaimed by the Christian troops in his army, victorious over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312. This imprecise reference, possibly even a covert allusion to the comity between Constantine and Sol Invictus, represented on the east end of his Roman arch, was soon strengthened. The Chi Rho, the monogram of Christ, appeared in Constantine's coins and medallions (no. 57) alluding to the sign, either the Chi Rho or the cross, seen by Constantine in the sky before the battle and subsequently adopted as his primary insignia.

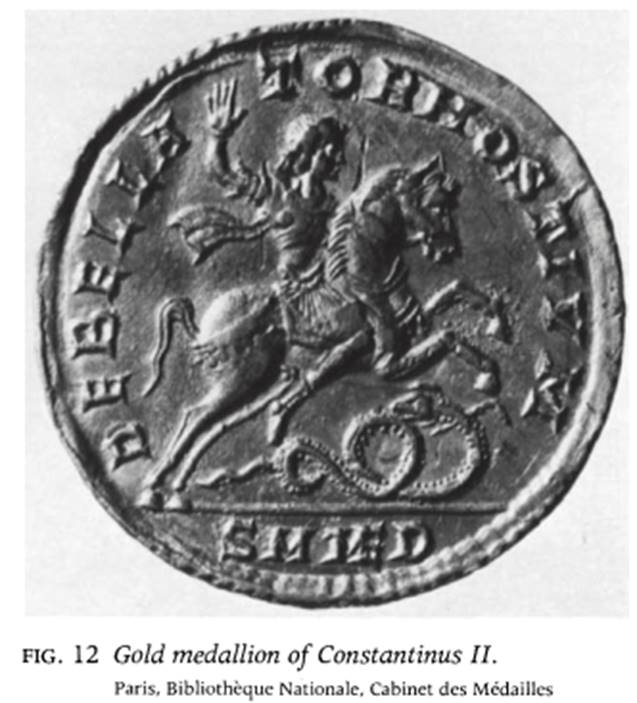

The intrusion of Christian symbols into the tradition of triumphal representation became stronger in the column of Arcadius (no. 68), erected in honor of himself and his brother, Honorius, to commemorate the victory over the Ostrogoth Gainas in 400. The idea of the triumphal column, erected on a high base and decorated with helical reliefs, was derived from the famous monuments of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius in Rome, but with an important difference: Christian symbolism now dominated the reliefs of the column base (no. 68): the source of victory lies beyond the emperors in Christ, and the partnership of the two emperors (concordia augustorum) and of the East and West parts of the empire has taken shelter under the sign of the cross. Likewise, a gnostic conflict of good and evil modified the familiar equestrian motif: not a human enemy but a serpent was depicted under the rearing front hooves of the war horse, personifying the usurper Mag- nentius in the fourth century (fig. 12), Attila in the fifth century, and the arch-foe of the heroic martial saint, St. George.

Nevertheless, the traditional iconography of victory continued. The strident notion of invincibility joined with total victory over the whole world was essentially a creation of the third century and of the First Tetrarchy, a period when insistent propaganda displaced the unpleasant facts of military struggle. Even on the column of Arcadius, the narrative of the helical reliefs was secondary to the highly formal images of majestic dominance versus a supplicating and defeated enemy, presented on the column base.

Since representations of warfare were staged as dramas, their function was not to indicate a fact or event but to characterize the foregone conclusion of Roman victory. By extension to any contest in which the character of the protagonist was shown in possession of virtus—the positive, courageous power that lies within a person, according to Stoic doctrine —victory in any field of action indicated both the favor of deity and the virtus of the successful actor. This predisposition could be safely tested in sublimated conflict situations where virtus could be revealed: the hunt and the circus/arena, the former aristocratic and restricted, the latter popular and intensely public.

The hunting of dangerous game had evolved in Hellenistic times as a sport of nobles and kings, as a kind of private warfare for display of courage and as a vehicle for self-aggrandizement. This tradition was enthusiastically continued by Roman rulers and aristocrats on their great country estates (fig. 13), in part indicating their great wealth, through the conspicuous waste of slaughter. Hadrian had developed the hunt as a symbolic field for the display of virtus, which he celebrated in a quasitriumphal monument, later preserved in the Hadrianic tondi on the facades of the Arch of Constantine (no. 58; the portraits of Hadrian were converted in the fourth century to those of Constantine and his father, Constantius Chlorus).

This usage applied not only to the triumphant huntsman, the surrogate of the triumphant warrior, but could also be extended in many Roman hunt sarcophagi of the second, third, and fourth centuries to the ultimate victory in the most pressing contest of all for a human being, the struggle against and over death (fig. 14). Thus, what had been an aristocratic sport, a cultivated field for winning acclaim and an opportunity for ostentatious display, became in the end an eschatalogical dream, a hope of ultimate victory, soon to be found only through the Christian faith.

The manifestation of virtus and the achievement of glory were primary motivations for emperor and aristocrat alike. When translated to the masses, the vicarious experience of violence certainly held the attention of the populace in those great centers of institutionalized violence perfected by the Romans for their enjoyment: the circus and the arena. Despite Christian opposition (Tertullian, Lactantius), the chariot races in the circus and the gladiatorial contests in the arena were conducted for centuries, entertaining the poor with lavish spectacles paid for by the rich and powerful. Crowds, noise, excitement, drinking, and death were all part of the sport scene, which continued long after the empire became Christianized. The games may have continued because they were deeply entrenched as customs and served to sublimate the smoldering rebelliousness among the urban proletariat; in any case, the gladiatorial contests in the arena (no. 82) and the chariot races in the circus (nos. 89-91) were prized by all. Factions of the racing teams—red, blue, white, and green—were fanatic in their allegiance, often breaking out in riots with an undertone of political protest. The games gave another opportunity for popular sport heros, gladiators and charioteers (nos. 94-96), but also by implication the members of the regime, who were victorious by definition, infected everyone.

Since the hippodrome-circus provided a field of recurring triumphs and of continual renewal, the racecourse came to represent the cycle of the seasons (nos. 100,101), bringing renewed prosperity with victory to the Roman people, an association particularly marked when the four teams were in competition. The course was run around a central spina, adorned with images of Victory and great obelisks like celestial beacons (no. 91). Some of these obelisks survive; the most famous of them still stands in the hippodrome at Istanbul, representing the court of ostentatious self-indulgence to emperor and patrician, who appeared at the games in splendor from the tribunal (nos. 83, 84). The ceremonial nature of these presentations was frequently heightened by specific occasions such as the entrance into office of a consul at the New Year. The resultant pomp together with the games, especially in the increasingly popular circus, brought various aspects of Roman public and political life into intense ceremonial association. The celebration of "winning," not only by the Theodosius in reliefs on the base and his presidency not merely of the games but of the state as well (no. 99). It is the emperor—silent, frontal, majestic— who alone and forever presents the prize to the victor in the race; it is he, dominant in all public ceremonies, who is the immediate source of victory on earth, if not in heaven. // Richard Brilliant

Bibliography: Gage, 1933; Grabar,' 1936; Treitinger, 1938; Straub, 1939; Kahler, 1952; Bruun, 1966; MacMullen, 1966; Lippold, 1968; A. Alfoldi, 1970; Cameron, 1970; MacCormack, 1972; Hunger, 1974; Laubscher, 1975.

Date added: 2025-07-10; views: 197;