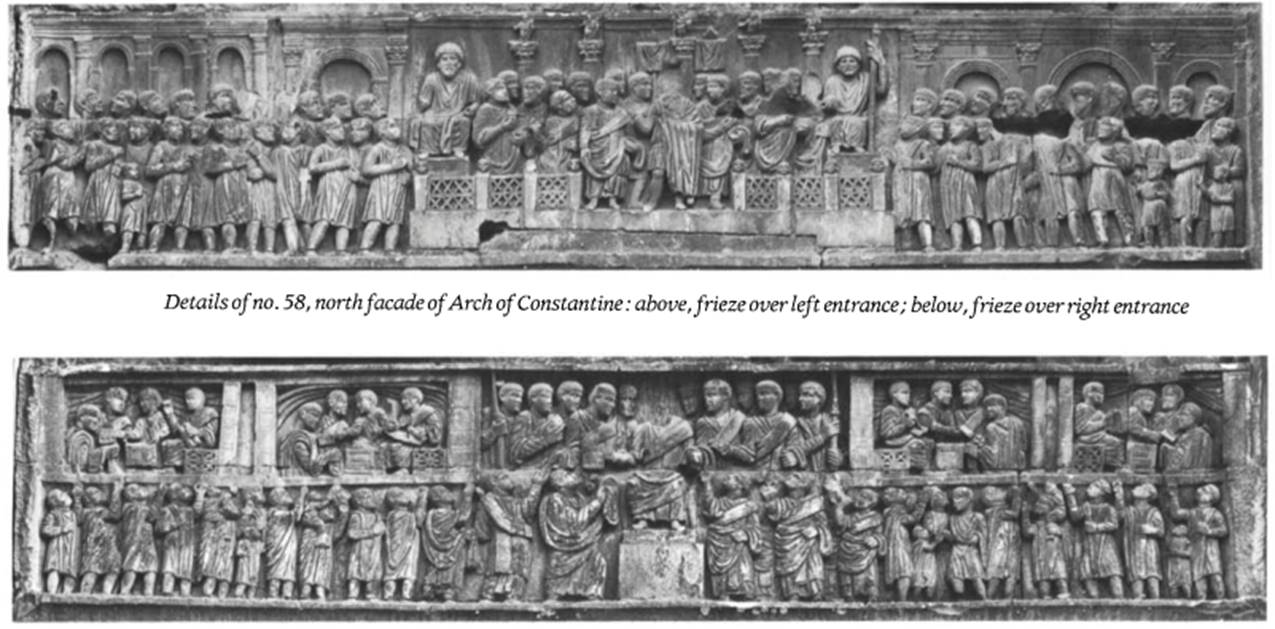

North facade of the Arch of Constantineю Rome, 315. Marble

The Arch of Constantine, commemorating Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 (cf. no. 57), was dedicated on 25 July 315, not coincidentally also the decennalia of his entrance into power. The arch incorporates several themes of Constantinian propaganda which extended the implications of victory and suggested the pivotal position of Constantine's rule between an old order, still great, and a new order rising from it to a glorious future.

The site chosen for the arch is important, because it lies next to the Flavian Colosseum at the bend in the triumphal route between the Flavian arches of Vespasian at the Circus Maximus and of Titus at the entry into the Forum. Since the first Flavians had established their power by the conquest of Jerusalem, the new Flavian emperor, Constantine, had conquered both Rome and Jerusalem, if one can assume that the words instinctv divinitatis in the inscription refer to the famous vision of the cross, which brought enlightenment and victory to Constantine.

The arch is full of deliberate echoes of the Roman past, indicating Constantine's role as a continuator, revealed by the many fragments taken from earlier monuments and put under Constantine's control in his own monument: reliefs and statues from a triumphal monument of Trajan, eight tondi from a Hadrianic monument, and eight panels from a triumphal arch of Marcus Aurelius. Confirming this reuse of the past, the original imperial portraits were replaced by the head of Constantine, with a few special exceptions in the Hadrianic tondi, thus assimilating these great persons into the present majesty of Constantine. In addition, Trajan's arch at Benevento influenced the design of the Constantinian arch in that the two facades, similarly composed, were divided between the themes of war (south) and domestic policy (north). This division was reinforced by the inscriptions on the central passageway: fvndatori qvietis ("To the Founder of Peace") and liberatori vrbis ("To the Liberator of the City"), both set over complementary sections of the reused Trajanic relief.

On the north facade, a complex billboard of political messages, the following Constantinian reliefs appear: over the left entrance, the oratio of Constantine to the Roman people from the rostra in the Roman Forum, with the emperor (headless) shown front and center; over the right entrance, the largitio given by Constantine (headless, front and center) to the Roman people; in the spandrels of the side bays, the images of young and old river gods, symbolizing fertility and the boundaries of the world; and in the spandrels of the central bay, the figures of Victories holding trophies, held out to Roma on the keystone of the central arch; below the Victories personified seasons—Winter on the left, Spring on the right—mark the beginning of a new era. The column pedestals at the base of the arch show Victories with defeated enemy soldiers.

This iconography develops the interplay between themes of victory and of an ordered, prosperous world under imperial governance, but does not conceal the great variety of artistic styles in this assemblage of borrowed, adapted, and newly made sculptures. However, the use of borrowed elements neither indicates a lack of ability among the sculptors of the period nor the absence of a tradition. The inserted Constantinian portraits are masterful creations of an unknown artist, who was, perhaps, also responsible for other Constantinian portraits (no. 374). At the same time the abstract, symmetrical, hieratic composition of the Constantinian registers, their inorganic forms, and dense, almost cubist style emerge from anticlassical currents in Roman art of the late third century.

The correspondences between original and reused sculptures confirm the importance of the “fragmentary style" in Constantinian art. It is consistent with those syncretistic tendencies already at work in the assimilation of various pagan cults. With the interpenetration of Christianity and classical culture in the fourth to fifth century less than one hundred years after it was erected, the arch was invoked in an oration by the Christian poet Prudentius (C. Symm. 1. 461-510; dated 403-405) as a monument of Christian triumph, surely evidence that it had performed successfully the task of integrating its various images and the concepts they represent.

Bibliography: I/Orange and von Gerkan, 1939; Giuliano, 1955; Calza, 1959-1960; Ruysschaert, 1963; Bianchi Bandinelli, 1971, pp. 73-80.

Date added: 2025-07-10; views: 240;