Pagan Legacies: The Transformation of Classical Culture in Late Antiquity

The recollection of things past, precious symbols of a better time, maintained the traditions of Greco- Roman culture among those for whom the act of recollection itself served to reaffirm their connection with the classical world. Nostalgia stimulated memory and helped to preserve the ancient forms in Late Antique literature and art, often marked, as in the hymn above, by an exquisite sensibility. This retention of the past offered the rewards of old associations and provided escape from the difficulties of the Christian present. Conflicts could become acrimonious and unsettling, however, as in the dispute between the pagan aristocrat Symmachus and a militant St. Ambrose over the removal of the traditional Altar of Victory from the Senate House in Rome in the late fourth century. Yet the growing alienation from the patterns of classical civilization did lead eventually to the diminution of their ancient authority.

Increasingly, the externals, rather than the substance of traditional modes and images, survived either as lingering conventions or as affected signs of high culture. The gods and heroes of antiquity were often reduced to stock characters in storybook tales or they were elevated into an abstruse symbolic realm that robbed them of vitality. Similarly, the ancient repertory of myths, mythological motifs, personifications, and cosmic symbols persevered, because it was familiar, had decorative possibilities, and provided a useful shorthand in new contexts for which no substitute had yet been created. The Christian societies of the Mediterranean viewed the tradition more reverently, in keeping with the distinction between the imperial Greek culture of the East and the barbarized, vernacular pattern of the West. For this reason, the classical tradition retained a normative function in Byzantine high culture for centuries, while in the West only a small group of aristocrats and churchmen still held it fast as an essential part of education.

Much of the classical literary and figural tradition was relegated to a marginal existence. Survival for the works of most ancient authors came to depend on whether they were considered worthy enough to be included in the anthologies and handbooks composed for students and “educated" persons. This progressive decline in erudition, with the loss of bilinguality, produced volumes of excerpted quotations, typified by the anthologies of Athenaeus in the third century, Macrobius in the late fifth century, and Nonnus in the sixth century. Thus, a taste for the telling fragment, the spoliation of the past, characterized much of Late Antique literature, and a comparable attitude colored works of fine art. As always, great writers and artists transcended these limitations, but their lesser contemporaries mined the debris of classical imagery, nonetheless, often presenting their finds in an exquisite manner (nos. 110, 130).

The classical gods were old friends developing new relationships. Protagonists of so much of antique literature and art, they survived in decreasing numbers in conventional situations, artificial topoi charged with special didactic functions that gradually came to dominate their imagery. Late Antique artists discovered that the moral order embodied by the pagan gods could be made congenial to Christian interpretation.

Zeus (Jove, Jupiter) played the role of the principal god who presided over heaven and earth, ruled the assembly of Olympian deities, and governed an orderly universe. As such he was primarily an image of majesty. The Senior Augustus, Diocletian, for example, took the epithet "Iovius" to indicate his authority and so his image appeared in the imperial octagon at Thessalonike (fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Pilaster capital with Zeus from the imperial octagon. Thessalonike, Archaeological Museum

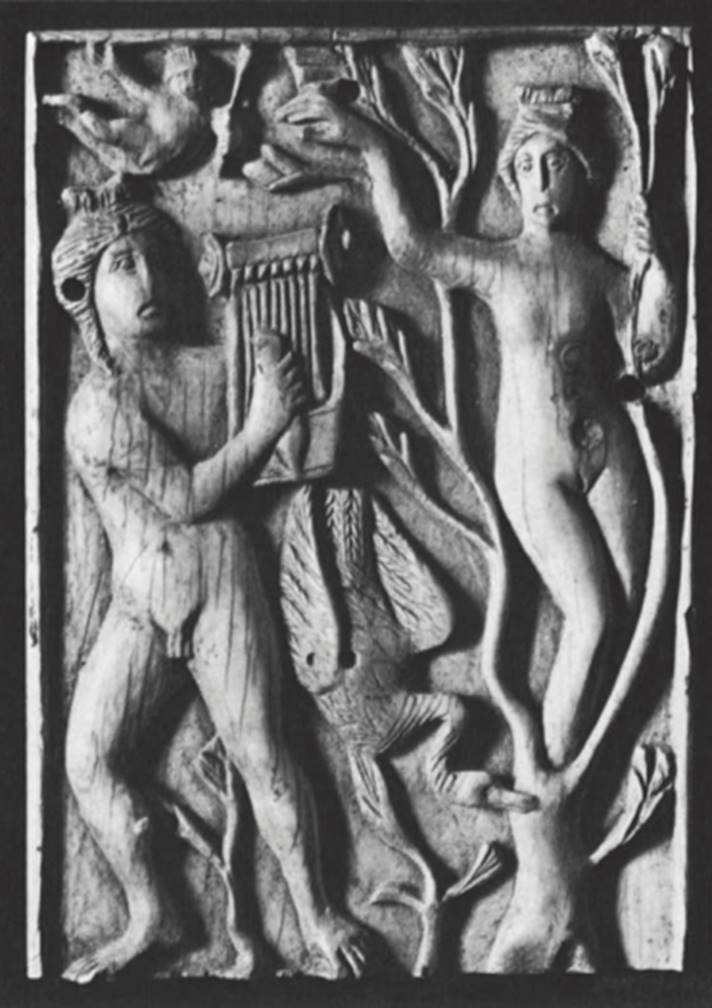

The very popular figure of Athena (Minerva) invoked the capacity of mind, the function of the intellect under the control of reason. As patroness of great Athens and of Athenian philosophy, Athena stimulated the intellectual strength of Heracles (no. 118). In an extension of her character the frequent association of Athena and the Dioscuri not only alluded to their common derivation from Zeus but, also, to their celestial, even ethereal nature. Although Athena was sometimes represented in company with Apollo (no. 110) as a source of mental activity, it was his distinction to illuminate the mind through inspiration, a prized conceit of artistic creativity which often involves the muses (nos. 242-244). Apollo, however, had a darker side: he punished the satyr Marsyas (no. 113) with a terrible death, although Marsyas lived on as a symbol of possession (by music) and as a demonic spirit whose flouting of authority was viewed as a challenge to order. Apollo, in conjunction with his sister, Artemis (Diana), slew the children of Niobe and ran after unwilling maidens like Daphne (fig. 16), who magically changed into a tree to avoid him. Perhaps his frustration echoed the ambivalence of Artemis, patroness of the violent hunt but symbol of chastity. If her first role pleased the aristocrats, enthusiasts of the chase, her second gave some comfort to the Christians.

Fig. 16. Ivory plaque with Apollo and Daphne. Ravenna, Museo Nazionale

All of these deities—Zeus, Athena, Apollo, and Artemis—enjoyed continuous favor, because their representations carried moral implications of general applicability without respect to their "pagan" origins. The same motives affected the abundant representation of Asklepios and Hygieia (no. 133), since everyone was concerned with health as a positive physical state, complementary to a condition of spiritual purity. In this context it is perfectly consistent that the hospital on the Tiber Island in the center of Rome could shift from the patronage of Asklepios to that of S. Bartolomeo without any change in function.

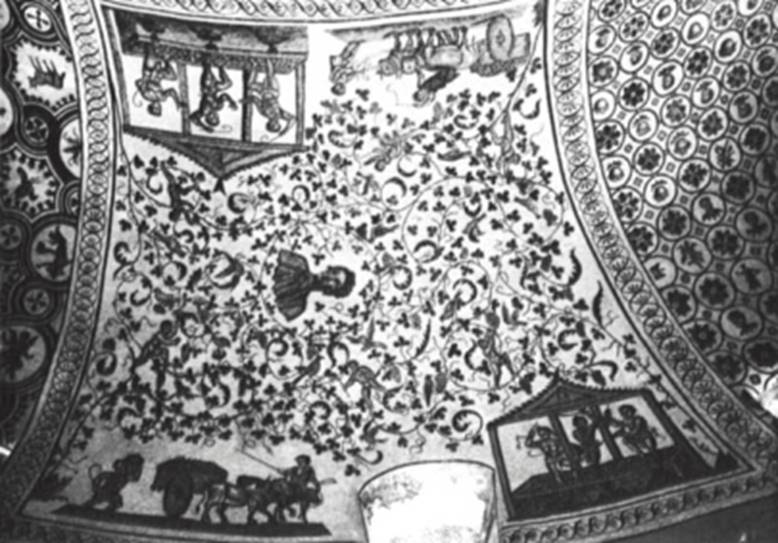

Dionysos, center of an active cult, appeared frequently and in various guises (nos. 120-123). His enduring popularity as a saving god was ritually served in the drinking of wine; both ceremony and belief in his soterial powers were transferred to Christ by Christian communities. Many Early Christian monuments, especially those associated with the fact of death and the promise of resurrection, employ references to Dionysos (fig. 17). Dionysos was the god of ecstatic release through wine and revel, and the overt hedonism of the cult, with its deep origin in the harvest festival, never died (no. 130). His most complete realization in myth occurred in the famous rescue of Ariadne on Naxos (no. 125), the isle of wine, which combined epiphany, salvation, triumph, and love.

Fig. 17. Vault mosaic with Dionysiac vendemnia. Rome, Sta. Costanza

Aphrodite (Venus) played her traditional role as the goddess of physical love; her blandishments conquered even the force of Mars and revived her dying lover Adonis (no. 119). In late antiquity, the deemphasis of her sexual powers and thus of her terrestrial nature heightened her role as the celestial Venus, the bright planet in the sky; in this guise she assumed some of the qualities of Athena as a stimulus of mental activity. Neoplatonic interpretations of Venus as inspirer of men, which eventually reached their apogee in the Renaissance, only served to remove more completely the taint of physicality.

Greek heroes and their exploits continued to appeal to all levels of a society cultivated by "classical" education steeped in the legends of the Greeks, titillated by novelle of love and adventure, and simply amused and comforted by the presence of champions. Although the tales of heroic adventure provided many avenues of vicarious escape, heroes, like Achilles (nos. 197, 207-213) and Heracles (nos. 136-140, 205, 206), who were much larger than life, had become familiar inhabitants of the mental world of the classical past and no less so of its figured arts. A vast repertory of images was repeated and gradually condensed into well-established motifs and cycles. This new paideia of the suffering hero who died triumphant and achieved immortality, drawn from the context of Greek thought, also provided an analogue to the life of Christ.

Perhaps the prime subject for such treatment was Heracles—man, superman, and demigod—who eventually rose up to heaven; his life story—from stressful infancy through the labors of his maturity (no. 136) to death by betrayal and his ultimate transfiguration—lent itself readily to ethical interpretation, whether Platonic, Stoic, or Christian. Like the biblical David, Heracles transcended the limitations of physical prowess, although he was patron of the arena and of gladiators; he struggled, often prevailed, was victimized by his passions, but retained to the end his spiritual quality. Although the Tetrarch Maximianus assumed his beneficent protection (no. 135), Heracles also served ordinary mortals at the moment of greatest danger, their death, since he could pass through the gates of Hades unscathed. As indicated by the many representations of the Alcestis story on Roman sarcophagi and Christian tombs (no. 219), this theme of rescue and resurrection had broad appeal.

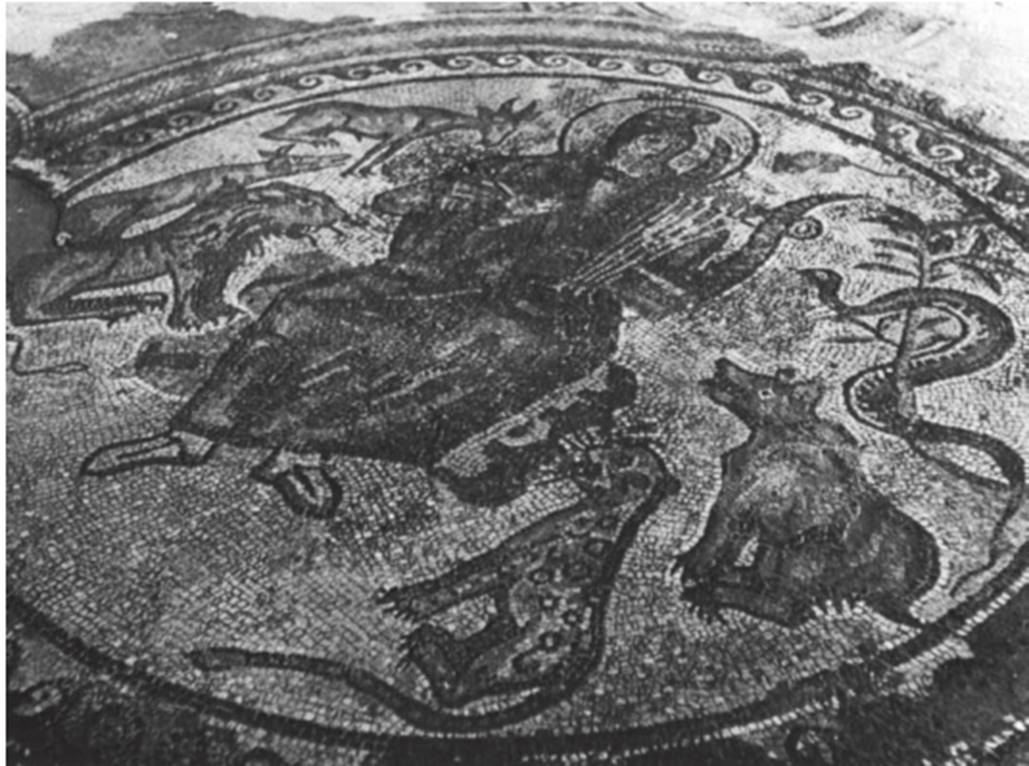

Some heroes lacked this nobility of character but possessed qualities still prized in a Christian world. Such was Meleager (nos. 141, 142), the epitome of the brave, rash hunter, who was involved in an adventure with Atalanta that brought both of them to destruction by offending Artemis and Zeus. Bellerophon (nos. 112, 144, 145), the celestial hero, tamer of the winged horse Pegasus and slayer of the monster Chimera (no. 143) rose like Meleager as an aristocratic hero, only to be devastated in his pride by Zeus. The transition from Bellerophon to St. George was readily made, and the appearance of Bellerophon in Early Christian mosaics (fig. 18) suggests the development of a Christian gloss which emphasized the positive qualities of the hero, his ascent, and his destruction of the evil monster. Similarly, Zeus' rape of Europa (no. 147) and of Ganymede (no. 148) may have come to stand more for the rapture of the soul by deity than the erotic possession of the body. The old protagonists of ancient epic survived, champions of a golden age. In Late Antique art, the spirited companions of the gods still danced (no. 128) and the ancient creatures of land and sea (nos. 150-152) displayed the forceful joys of nature.

Fig. 18. Mosaic of Bellerophon, from Hinton St. Mary. London, British Museum

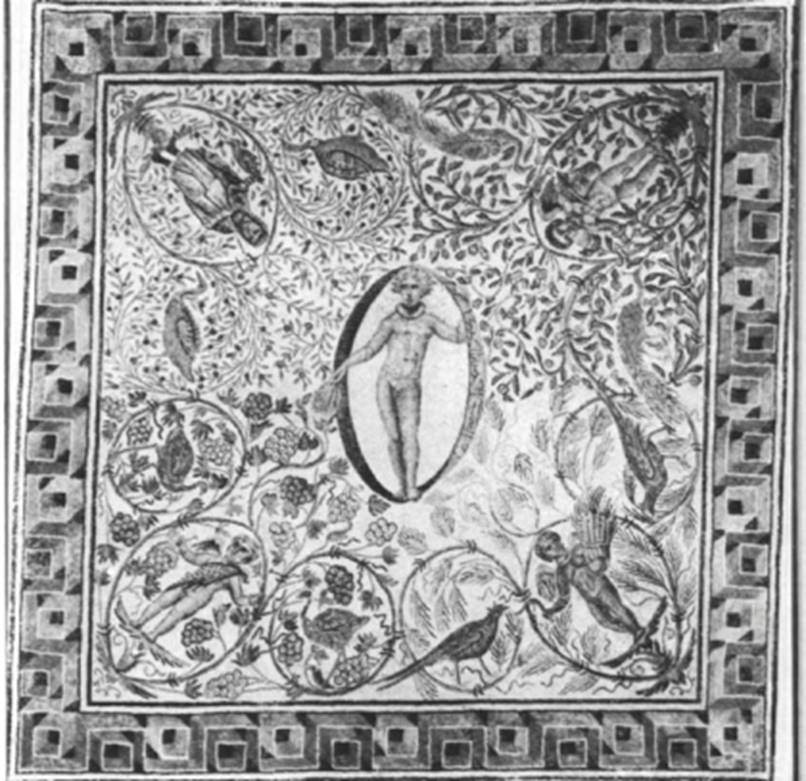

Nothing in classical imagery survived more strongly than the personification of the seasons and times of the year (fig. 19), the fruitful bounty of the earth (no. 159), the elements of nature (no. 164), and the extensions of the cosmos (fig. 20).

Fig. 19. Mosaic with Aion and the four seasons, from Tunisia. New York, United Nations

Fig. 20. Bronze lamp with Triton, Sol, and Luna. Florence, Museo Archeologico

Personification as a system that converted abstractions into human form developed during the Hellenistic period, especially at Alexandria, where the practice flourished in poetry and art. The use of Tyche to personify cities (nos. 153-156) provided a coherent resolution to a complex subject. Yet, these symbolic evocations tended to congeal into schemata that gradually substituted for scientific thought and observation. The primitive, even animalistic view of natural science evident in the encyclopedic works of Isidore in the seventh century indicates the retrograde course of this development when compared with Aratus' astronomical poem, Phaenomena, in the third century b.c., Pliny's Naturalis Historia in the first century a.d., and Ptolemy's Geographia in the second century a.d.

The mystery cults were very much part of the heterodox world of the Roman Empire, a manifestation of the irrational in ancient culture. The magic in signs was brought to bear on the iconography of these cults, whose governing deities and submissive celebrants sought to confirm the good life on earth and the likelihood of salvation. The resultant imagery of cosmic power, asserted by many competing deities, reflected the syncretism of late Roman private religion toward a singular objective: the search for help. Between deity and devotee the relationship became direct and personal, filled with the aura of the immanent god, especially Mithras (fig. 21; nos. 173-175). Mithras' epiphany offered a moving revelation that changed men's souls for the better. Mithras often appeared engaged in the act of cosmic sacrifice, thus assuring life's continuance, supported by figured episodes illustrating his divine history. His cult was celebrated by worshipers in communion, sharing a dogmatic belief and an institutionalized structure organized around a priesthood and progressive degrees of initiation.

Fig. 21. Painted relief with Mithras. Rome, S. Stefano Rotondo

Ecstasy played a major role in cult observances, frequently in connection with cycles of renewal centered in the dying/rising male god, partner to a mother/wife (nos. 164, 169, 170; Cybele, Isis) in sacred consortium. Older cults, like those of Dionysos (nos. 121-126) and Orpheus (fig. 22; nos. 161, 162) preserved traces of their primitive, preurban origins: Orpheus, singer of soothing songs, appeared as the Good Shepherd (nos. 464-466), who guarded his flock from danger like David and Christ.

Fig. 22. Mosaic with Orpheus. Tolmeita (ancient Ptolemais), Cyrenaica

Pervading these cults were certain basic features: lack of originality, individual access to deity but within a community or congregation, the importance of revelation, and, above all, an imagery of intense belief. These features suggest that a desperate need for deity existed, a need met by a proliferation of religious images to serve the cult and to exalt the worshiper. The cults provided models for Christian practice, not always appreciated by Christians.

He [Mithras] baptizes some; he promises the removal of sins by the laver; and if my memory is sound Mithras even signs his soldiers right on the forehead; he also celebrates the oblation of bread, and brings in a symbol of the resurrection .. . and under the sword wreathes a crown. ... He even limits his high priest to a single marriage. And he also has his virgins, and likewise his celibates.... (Tertullian De praescriptione haereticomm 40 [Grant, 1957, p. 245]) Richard Brilliant

Bibliography: Eisler, 1925; A. Alfoldi, 1937; Cochrane, 1944; Momigliano, 1955; M. Simon, 1955; Nilsson, 1957; Kerenyi, 1959; E. Simon, 1964; Brandenburg, 1968; Campbell, 1968; Matthews, 1973; Huskinson, 1974.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 190;