Beyond Spolia: The Evolving Role of Classical Orders in Late Antique Church Architecture

If the attitude of late antiquity to its classical architectural heritage can be gauged by what we today call historic preservation, the evidence is ambiguous, and nowhere more so than in Rome and Athens. The age opened with careful reconstruction, by the First Tetrarchy and Maxentius, of fire-damaged buildings in and near the old Forum Romanum, some of which went back to the time of Caesar and Augustus, in precisely or approximately their original form. Among these was Maxentius' reconstruction of Hadrian's Temple of Venus and Roma, a huge, many- columned structure modeled on the vast temples of late classical Ionia. This concern for the perpetuation of old monuments may be attributed more to political than to artistic reasons, in which the structures' historical significance bore greater weight than their aesthetic qualities, although the two are difficult to separate.

At the same time, the Romans continued the longstanding practice of cannibalizing old buildings, especially unused buildings, for their salvageable parts. This could get out of hand, as is documented by many decrees limiting or forbidding the practice. One, from 458, begins: “The emperors Leo and Majorian to Aemilianus, City Prefect. While we govern the state, we are anxious to correct obnoxious practices which have long been allowed to deface the appearance of the Venerable City [Rome]. For it is obvious that public buildings, wherein consists the whole beauty of the Roman state, are on all sides being destroyed by the most deplorable connivance of the city administration" (Dudley, 1967, p. 32).

The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis was converted to a Christian church, with remarkably minor alterations, probably late in the sixth century (fig. 29). In the next century, apparently, the Erech- theum and the Hephaisteion (“Theseum") were also consecrated as churches. These transformations, only three of many dedications of pagan temples as churches from the fifth century on, appear to have been prompted less from a deep appreciation of the beauty of these monuments or from an interest in aesthetic heritage than from political and emotional demonstration of the triumph of the Church in the heart of the pagan world.

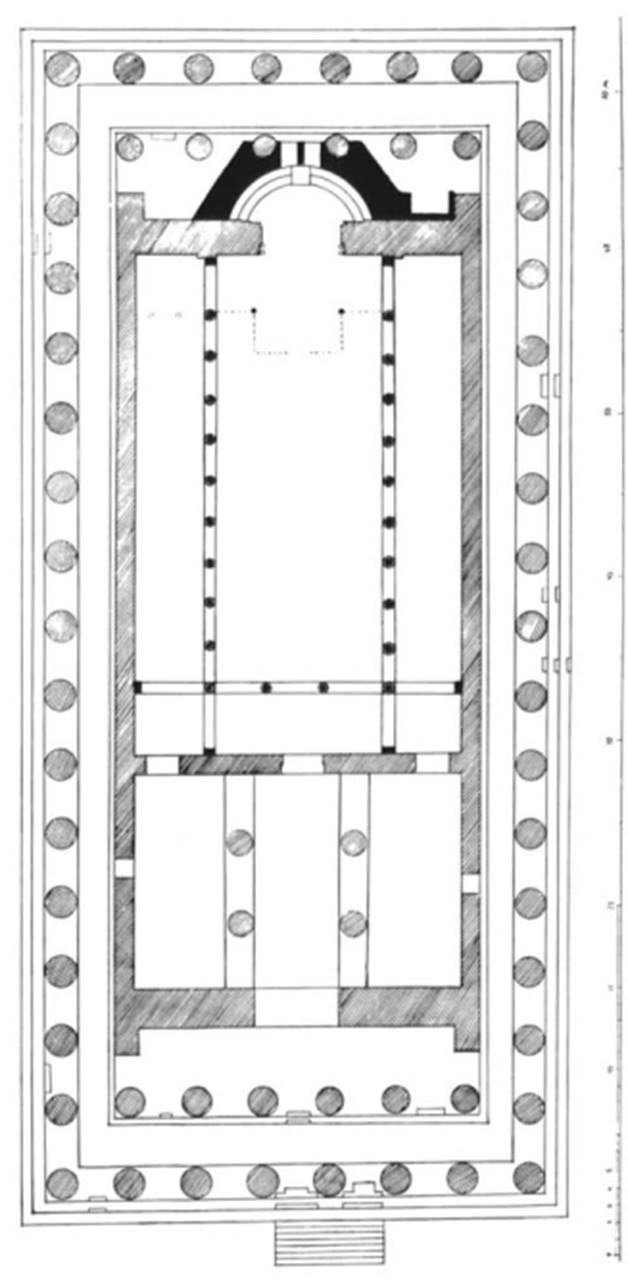

Fig. 29. Plan of sixth-century Christian church in the Parthenon, Athens

The role of the classical heritage in the architecture of the late Roman world was necessarily different from the one that it played in the representational arts. Painting and sculpture are imbued with literary conceptions, both in subject and in such expressive means as metaphor, allegory, and narration. The representational arts lend themselves far more easily to flights of fancy, to expressions of nostalgia, and to the individual statement of opposition to a predominantly aclassical culture. Architecture is inherently more the servant of the dominant culture than these arts. Constantine could furnish his baths in Rome with statues ultimately derived from works in the high classical style, and his mother, Helena, could be portrayed as a seated figure from the same period; but although the Parthenon and the Pantheon, like monumental spolia, were much later converted to churches, the new churches commissioned by Constantine and his successors did not and probably could not imitate successfully the monuments of the classical past. But almost all of them, nonetheless, did contain elements of the old classical orders, sometimes adopted unconsciously and sometimes chosen deliberately as status symbols of an honored architectural heritage.

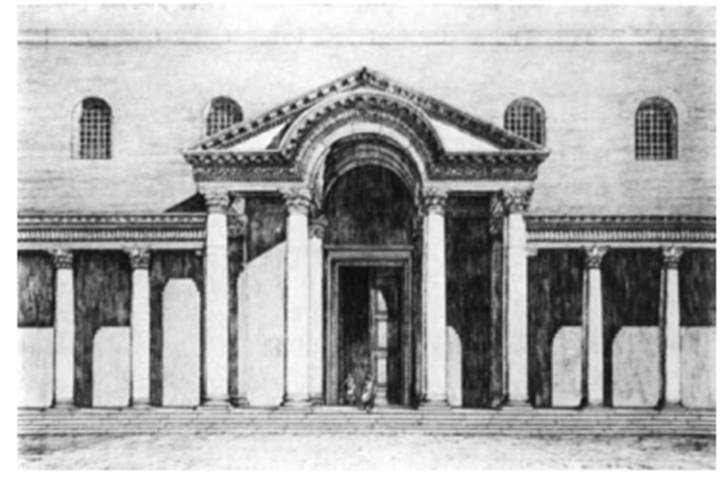

The order was the product of the transformation of the post-and-beam structural system by the Greeks of the archaic and classical periods into an equivalent artistic schema, each of whose elements of load and support were integrally related to the whole by a system of formal and proportional relationships. These relationships were long maintained even when, in the Hellenistic and especially in the Roman period, the order was applied as an artistic and cultural articulation to different structural systems, specifically to solid walls and to arched constructions. Even in the late Roman period, in such Christian buildings as Sta. Maria Maggiore at Rome (figs. 93, 94) in its interior and Theodosius II's Hagia Sophia at Constantinople (fig. 30) in its propylon, the classical orders appeared in substantially their original coherence. These were the exceptions, however, sometimes interpreted as conscious allusions to a classical past reevaluated. In the main, the transference of the order from a primarily structural to a chiefly articula- tive role began a devolution in which the order lost much of its immediacy and vitality, a process that was completed in the late Roman period.

Fig. 30. Drawing of propylon of Theodosius II, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

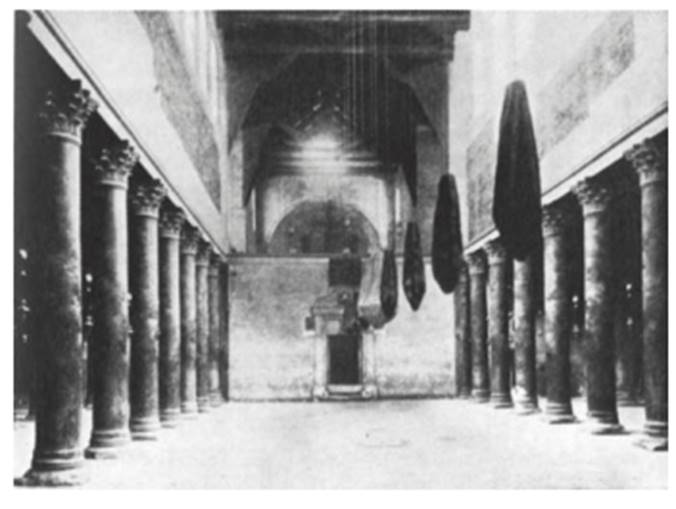

The real classical contribution to the architecture of the period was the paradigm of post-and-beam poetry that the order offered, to the formation of a new “order" based on the arcade. The evolution of the new order was not a continuous, smooth pattern of development; it can be traced in a few examples chosen from the time of Constantine to that of Justinian. The arcade, arches supported on freestanding columns, had appeared as early as the first century b.c., in which the classical horizontal entablature was replaced by archivolts molded to resemble semicircular architraves. These were separated from the capitals of the columns beneath them by isolated, residual blocks of entablature, much as they were still to be found in the fourth century in the interior of Sta. Costanza (no. 246). Although this mixture of the trabeated and arcuated did not put the older, purely trabeated colonnade completely to rout—witness Old St. Peter's (no. 581) and even Justinian's Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (fig. 31)—the arcade was the predominant system of internal support and articulation in the late Roman world, East and West.

Fig. 31. Interior of the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem

In the arcade system, as in all others, junctions are of special importance, particularly the junction of the elements of load and support. The square abacus of the classical capital, with the Doric cushion or the Ionic or Corinthian volutes beneath it, was beautifully suited to receive and to channel the visual force of the horizontal beam above it to the column shaft below. It was less well adapted to assume the same role below arches, as is easily seen in Sta. Sabina at Rome (no. 247), where the arches are frankly placed on reused capitals with no intermediary element. The undeniable beauty of the arcade at Sta. Sabina derives from its discrete elements and not from an artistic harmony of structural elements. This arcade illustrates another problem the system presents. A pure semicircular arch appears to be slightly flattened; thus, the architect's problem was to elevate the arch without overcompensating for the optical illusion. At Sta. Sabina the arch is slightly stilted. Ways in which both problems were simultaneously solved in the fifth century are seen in the clerestory of the Baptistery of the Orthodox (no. 588) or at S. Apollinare Nuovo at Ravenna (no. 248) and in the galleries of the Church of the Virgin Acheiropoietos in Thessalonike (no. 587).

In Ravenna, the isolated entablature block was replaced by a simple inverted truncated pyramid called an impost, or stilt, block, whose upper surface corresponded to the base of the arches and whose lower surface fitted comfortably on the abacus of the column below it. The arch is a pure semicircle; the necessary elevation is accomplished by the stilt block. The stilt block was, nonetheless, something of an alien element, in that its extreme simplicity was frequently in strong contrast to the capital beneath it, as at S. Apollinare Nuovo. At Thessalonike, the impost and the capital were fused into a single structural, artistic element uniform in surface treatment and well suited to the physical and visual functions the capital served. A new "order" was achieved, while, in the residual volutes at the base of the capital, something of the symbolic value of the old Ionic capital was retained. There are many beautiful late Roman variants on the impost capital. Other capital forms were created, such as the so-called Theodosian capital exemplified by the main arcades of the Acheiropoietos (no. 587). The lands ringing the Aegean Sea played a leading role in these experiments: significantly, this was the homeland of the classical orders. Whereas in classical architecture the focus had been on the entire structural apparatus, in Late Antique architecture, the burning glass was focused on its capital alone.

Paradoxically, the outstanding exception to and the culmination of this quest for a new order is found in Justinian's Hagia Sophia (no. 592). The arcades of its ground floor rest directly on columns surmounted by exquisite permutations of the Corinthian capital. The old familiar elements are there: the bell sheathed in acanthus leaves, the volutes at the four upper corners, and the low abacus embellished with motifs of classical derivation. Yet the capitals and the arches above achieve a new and harmonious unity. This successful interpretation is based partly on the gentle swell of the capital, which acknowledges the weight it bears, and partly on the uniformity of the character and intensity of the patterned relief that covers the capital, the archivolts, and the spandrels in a seamless web of light and dark. In motif and in rationale, the old order shines through the new. Alfred Frazer. Bibliography: Kautzsch, 1936; Deichmann, 1940; Deichmann, 1956, esp. pp. 41-97; Deichmann, 1975.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 136;