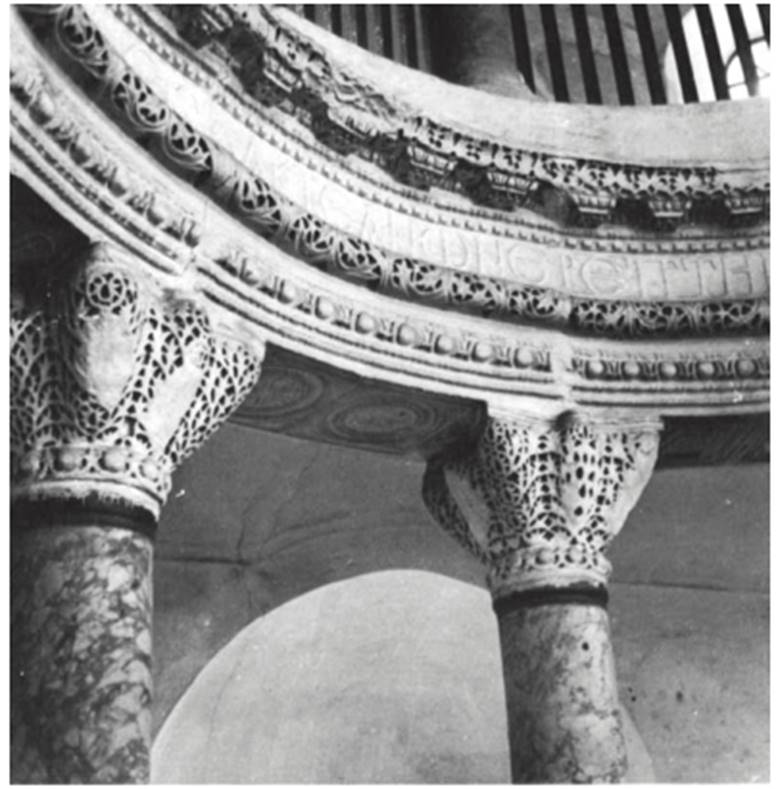

Order of SS. Sergios and Bacchos. Istanbul, about 527-536

The beautifully designed inscription in the frieze of the entablature that separates the main colonnade from the arcade states that the church was founded by the emperor Justinian and the empress Theodora, who acceded in 527. The inscription also documents that the church was complete by 536. Thus, SS. Sergios and Bacchos was begun shortly before Justinian's Hagia Sophia and completed at least a year earlier than the Great Church. Situated in a compound occupied by the imperial couple prior to their accession, SS. Sergios and Bacchos comprises a two-storied octagonal rotunda enveloped by an aisle and a gallery set within an irregularly quadrilateral exterior wall.

The imperial sponsorship is reflected in the church's size and its superb decoration, especially that of its architectural sculpture. This ornament is closely related to that of Hagia Sophia (no. 592) and represents a culmination of over a century of the development in Constantinopolitan architectural carving. The column shafts are of green and gray marble and the bases, capitals, and entablature are of gray white Proconnesian marble. The capitals of the colonnade are the so-called “folded" type (Faltkapitell), an Eastern late Roman impost capital developed from the classical Corinthian capital.

The emphasis on the centers of the four faces and on the four corners was retained in the projecting folds, but the traditional plastic articulation of rampant acanthus leaves and volutes and helices was replaced by a uniform, two-dimensional web of acanthus tendrils, here a jour. The entablature is a series of contradictory elements. Such traditional classical features as the three-fasciaed architrave, the frieze, and the bracketed cornice are combined with canonical decorative motifs: the egg and dart, the bead and reel, and the acanthus rinceau. The decorative meipbers are framed according to classical tradition by undecorated elements, but the decorated members, such as the moldings in the architrave, are larger than the framing elements.

The entablature possesses two friezes, the flat inscribed one and, more conspicuous and in apparent contradiction, a cushioned frieze (cf. no. 246). Despite these unclassical features, a visual harmony is achieved by the bold patterned carving, which unites frieze and cyma with the openwork carving of the capital. Bibliography: Kautzsch, 1936, pp. 187-189; Deichmann, 1956, pp. 72-76.

Visual Silence on Daily Life: Nature and Labor in Late Antique & Early Christian Art

The art of the Late Antique and Early Christian period gives us less information about the daily lives of the average man or woman of that time than it does about any other aspect of history or culture. There are no pictures of the wedding festival, or, for that matter, of any other domestic ritual. On funerary monuments, the deceased was portrayed as he wished to be remembered—at the height of his professional career. The sociologist will be disappointed that there is so little pictorial evidence concerning the private affairs of Greek or Roman citizens—such as married life, social contacts, the rearing and education of children, or the life and treatment of slaves. The themes deemed appropriate for the illustration of daily life were restricted to a few clearly defined categories, most of them shared by pagan and Christian art.

Artists of the period, however, did display a limited interest in the observation of nature. Some depictions may have been influenced by illustrations for bucolic poetry, such as the shepherd with his flock playing his flute or the peasant tilling his soil, which illustrated the Eclogues and Georgies of Vergil (nos. 224-225). Others, like the frescoes of a tomb chamber from Alexandria (no. 250) display a fresh look at nature: the workings of a waterwheel and the swampy shore of the Nile with its fowl and water plants have been keenly observed.

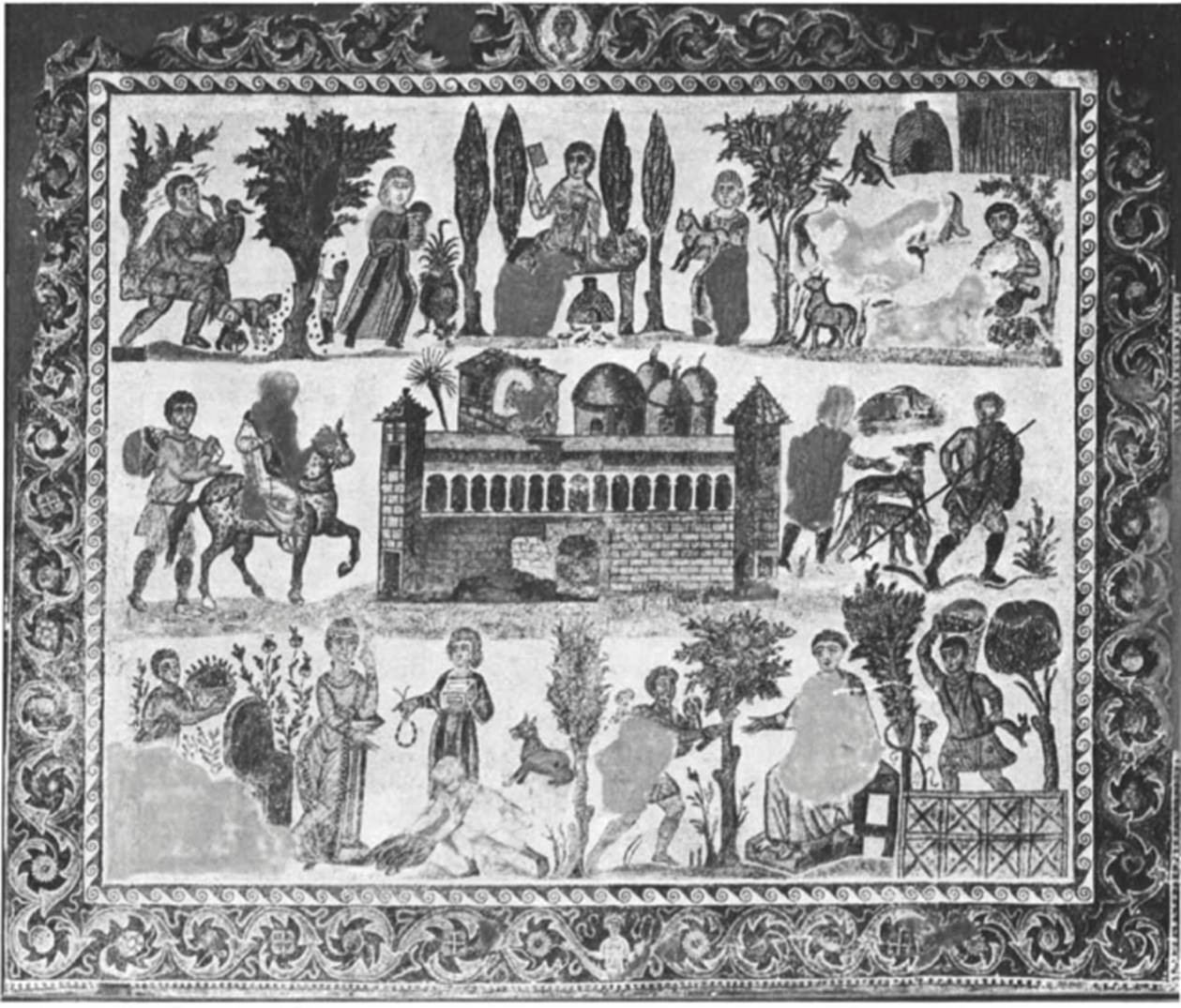

While the hunt is often depicted as the special prerogative of the emperor, by the Late Antique period other social classes had adopted this aristocratic sport. A North African mosaic (fig. 32) depicts the villa of a rich landowner surrounded by scenes of harvest and departure for the hunt. As with bucolic pictures, it is difficult to determine whether the artist worked from fresh observation or from conventional, traditional types. A similar ambiguity was represented in fishing scenes: extreme realism in the depiction of a variety of fishes, for which the sources were specialized treatises (cf. no. 185), is often coupled with such mythical touches as pygmies fishing in the Nile (no. 252). Frequently, elements of the Isis cult became associated with these Nilotic scenes (no. 170).

Fig. 32. Mosaic of Dominus Julius with scenes of country life. Tunis, Musee National du Bardo

Other favored outdoor occupations were hunting and fishing, which likewise were described and illustrated in detail in such didactic poems as Pseudo-Oppian's Cynegetica (fig. 24) and Oppian's Halieutika.

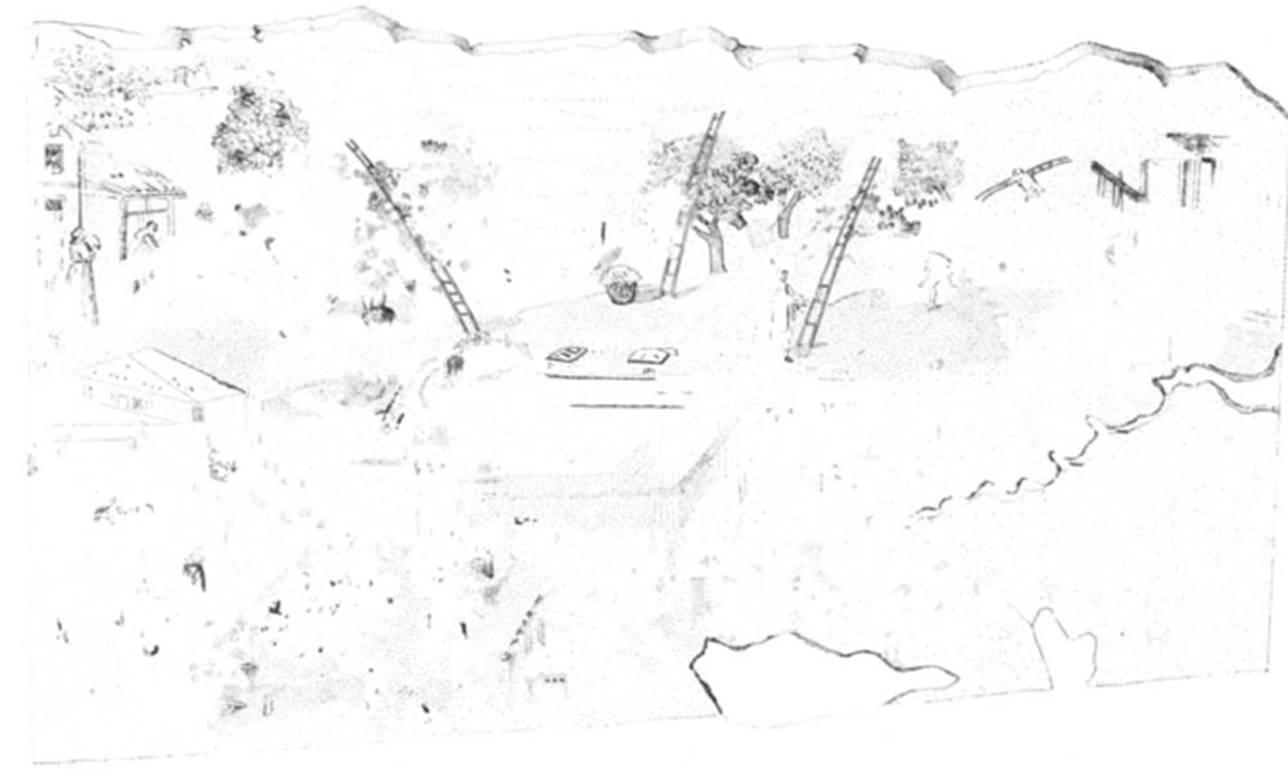

Many rural occupations were depicted according to the seasons, and a special set of occupations developed in connection with the calendar. Once more we notice the impact of a literary genre. How variegated and rich in observation such calendar pictures could be is demonstrated by the frescoes from around 300 recently discovered under the floor of Sta. Maria Maggiore in Rome (fig. 33), where for month of September the harvesting of fruit is shown in great detail.

Fig. 33. Drawing of the fresco of the month of September from Sta. Maria Maggiore, Rome

Particularly in Rome and the Latin West entirely different types of daily life pictures occur, which lack any connection with a tradition still steeped in mythology or with conventions derived from it. A self-assertive middle class of professionals and merchants had developed a taste for having themselves portrayed while practicing their occupations. A favored place for such a display was the tomb, in which the deceased was commemorated in this manner. The fresco decoration of the tomb of the architect Trebius Justus in Rome (no. 253) shows not only his portrait figure, but the actual building of a house in all its detail, telling us much about the building practices of that period. The deceased could also be depicted reading, surrounded by the books and implements of his trade, like the physician on a sarcophagus (no. 256). There is an obvious similarity between this physician and many evangelists who have before them a lectern and table with writing paraphernalia (no. 490).

Shop signs produced for the practically minded Roman businessman to advertise his trade in wine or grain (nos. 257—258) also show men at work. These are found as frescoes or marble plaques by the doorway of an artisan's or vendor's shop. Some of these marble reliefs, especially those found in Ostia, show a great variety of traders—among them, a seller of vegetables and a butcher behind his counter.

Late classical floor mosaics often employed scenes of daily life in considerable detail. In a Tunisian mosaic (no. 260) the unloading and weighing of a ship's cargo give an insight into maritime commerce. On a far more ambitious mosaic in the villa at Piazza Armerina, rare and exotic animals, including ostriches, a camel, an elephant, and a rhinoceros, are loaded onto a boat to be shipped to the owner of the villa, most likely the emperor Maximianus, for his zoo.

From family life only one event seems to have been represented, and quite often: the marriage ceremony. Here, the connection between pagan and Christian art is quite close (nos. 261-263), for in each the event is rendered in the same ceremonial manner prescribed by civil law, showing the joining of right hands (dextrarum junctio). The only difference is that the administrator of the rite is Juno pronuba in the pagan and Christ in the Christian representation. Kurt Weitzmann. Bibliography: Jahn, 1861; Magi, 1972; Precheur-Canonge, n.d.

Private portraiture followed a similar stylistic and conceptual development to imperial portraiture, and, thus, its chronology is largely dependent on comparison to identifiable imperial portraits. Nonetheless, the finest private portraits, being unique, are much finer in many cases than the routine replicas made for imperial propaganda.

Of course it is not always simple to establish which images represent rulers, and which do not, since members of a court tend to dress, cut their hair— actually look like their monarchs, while emperors and empresses may not always wear their crowns and regalia. This seems particularly problematic with female portraits, where artists are more tempted to idealize their subjects than with males. It would seem safe to presume that private citizens did follow the lead of imperial style-setting; but probably at an indeterminable lag of time—just as elderly ladies in our own time frequently prefer to dress in the fashions of their glamorous youth, rather than of the depressing present.

Private portraits were made over a wider geographic area than the imperial, whose manufacture must have been concentrated in the capital cities. This is particularly important in the East, where major centers of sculpture persisted with distinctive, often conservative styles. At Aphrodisias in Asia Minor, a "baroque" manner rich in plastic and dramatic expression can be traced from the reign of Hadrian until the middle or end of the fifth century. In this regard, our group of private portraits should be considered together with those of local officials and functionaries included above; once away from the court, such portraits were more likely to follow local fashion than those of Rome or Constantinople.

To some degree, this diffusion or radiation may be pursued beyond the actual boundaries of the Greco-Roman cultural empire. At the edge of its influence, in the areas where what has been termed "subantique" culture prevailed, traditional formulae of the Hellenic tradition were simplified into stereotypes that might well be viewed as folk art. Such are the later Egyptian mummy portraits (no. 266) or such locally produced images as the ceiling-tile portrait of the Roman soldier Heliodorus at Dura (no. 52).

Existing at an extended distance from the centers of culture whose impulses they still reflected, these iconic images actually forecast the future of the representational arts in the restructured empire itself.

The apparently growing predominance of female portraits in the later period may be an accident of preservation, but it may be actual: a similar trend occurs in the imperial series from the late fifth century onward. Curiously, recent research has revealed that a number of sixth-century male portraits were recut from earlier heads, while the notable female portraits appear to have been cut from new stone. A number of these female heads are of supremely high quality (nos. 268, 272).

The art of portraiture had experienced a brief flowering of particular splendor, in both imperial and private works; but by the mid-sixth century religious, that is, Christian, subjects seem to have preoccupied all levels of society, and the celebration of the secular individual ceased to be of much concern. It may be indicative of this shift in emphasis that, in the latest datable portraits surviving, the observer has difficulty deciding, not if an isolated image is private or official, but whether it is secular or religious.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 143;