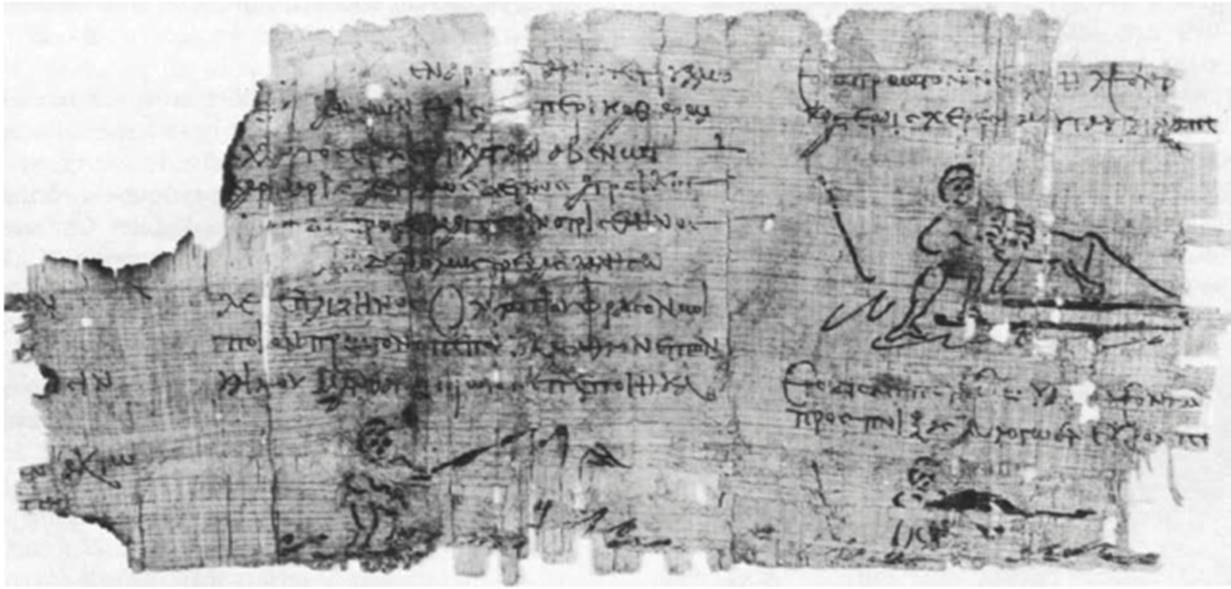

An illustrated poem about Heracles. Egypt, 3rd century. Papyrus

The fragment comes from a papyrus roll; two legible text columns survive with their illustrations. The subject is a doggerel poem, in the form of a dialogue between Heracles and an unidentified second person. They discuss the hero's first labor, the killing of the Nemean lion, and it seems probable that the rest of the poem dealt with his other labors. On the analogy of better-preserved literary papyri, we can assume that the lower part of the papyrus is missing. The illustrations are as sketchy and simple as those of the papyrus no. 222. The contours are defined by a heavy line, drawn quickly; colors (green and yellow) were applied freely.

In the first scene, Heracles is cutting his club. In the lines immediately above, the second character addresses the hero: "Say, O son of Zeus, tell me about the first labor that you did!" The reply is "Learn from me what I had done first of all." The illustration shows the hero holding the club against his left thigh; his left leg is raised. At the right is the wild olive tree from which he cut the club. The text explaining the action of the picture must have followed. For the cutting of the club, see no. 206. In the next scene, to the right and above the first, Heracles has set the club down and wrestles with the Nemean lion.

The text explains that he killed the lion with his "strong arms"—for it was otherwise invulnerable. The lion is shown on slightly higher ground, as in other Egyptian depictions of the scene; the iconography is similar to the ivory plaque no. 206, although the figures are reversed. The last scene is hard to make out. The text above mentions that having strangled the lion he laid it out dead; the miniature has been interpreted as either showing Heracles with the lion skin which will henceforth become his attribute (Weitzmann in Roberts, 1954) or the hero standing before the dead lion (Kenfield, 1975).

Along with the Paris romance fragment no. 222, the Heracles papyrus is one of the most important pieces of evidence for the nature of illustrations in Greek literary papyri. These are seen to have a minimum of scenery and no background; they concentrate instead on the narrative action of the characters and are inserted into the text at appropriate places. The cycle here must have been very dense, as can be seen from the two scenes in column two. It is on such evidence as this that we can hypothetically reconstruct illustrated papyrus models for cycles of illustrations that survive in other media (as, for instance, in the Achilles cycle of nos. 207-213). Found at Oxyrhynchos in Egypt. Bibliography: Weitzmann in Roberts, 1954, pp. 85-87; Page, 1957; Maas, 1958; Weitzmann, 1959, p. 53; Kenfield, 1975.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 140;