Plate with Achilles and Briseis. Place of origin unknown, 4th century. Silver

This very large plate, or missorium, has a low foot. The surface is filled by a mythological scene surrounded by a border of pomegranates. There is a long tear between border and central scene from the upper left to lower right. This has been repaired by rivets from the back. Extensive damage at the raised knee of the nude figure at the lower right has also been repaired in modern times. There are traces of gilding on the stool at the center and on the hair and helmets of the figures at the right. Two modern coats-of-arms are engraved on the back of the plate.

The mythological representation contains references to at least three critical events in the participation of Achilles in the Trojan War. In the center the beardless man, his garment fallen from his chest, must be Achilles. He is seated frontally but turns to the right to a bearded man in a short chiton. On the left is the most easily identifiable group: Patroclus leads Briseis from Achilles' tent (Horn. 77. 1. 326-356). Chabouillet's (1858) interpretation of the scene as the reconciliation of Agamemnon and Achilles (17. 19. 184-337) has been rejected convincingly by Levi (1947, I) and Carandini (1963-1964). Yet in the Iliad Agamemnon's heralds do not speak to Achilles. It is therefore impossible that the bearded man with whom Achilles speaks is a herald; his manner of dress and his bearing are hardly humble.

The heralds are, in fact, certainly the helmeted figures farther to the right. A scene commonly conflated with the departure of Briseis is the arrival of the embassy of Phoenix (Horn. II. 9. 162-657). Thus, on this plate, Achilles is addressing Odysseus, who spoke for the embassy. The table on the extreme right, with a vase and other objects, must refer to the banquet held on this occasion. The other figures around Achilles should be Phoenix and Ajax and the Myrmidons, Achilles' companions. The strange nude man seated at the lower right remains unexplained by this conflation. Around his waist is slung a sword. A similar nude figure on a silver vase of early imperial date found at Bernay in France and now in the Bibliotheque Nationale (Carandini, 1963-1964, p. 16, fig. A) is connected with the death of Patroclus.

The scattered weapons at the bottom probably refer to the general theme of battle, yet a silver plate in Leningrad (no. 202) of a later period depicts Athena presiding over the distribution of Achilles' arms after his death. On the left of no. 202 is a large nude Ajax, who can be compared with the seated figures of this plate and the Bernay vase. On the right of no. 202 is Odysseus in a pose comparable to the figure identified as Odysseus on this plate. In the lower segment of no. 202 are a helmet, cuirass, and boots, the armor of Achilles. These may simply have been multiplied and varied on the plate here. Thus, this plate contains references to the three events in the participation of Achilles in the Trojan War: the leading away of Briseis, the embassy of Phoenix, and the death of Patroclus. A possible reference to a fourth event, the death of Achilles, may be seen in the armor.

The plate is difficult to date with precision but resembles in ornament and style other silver plates of the fourth century. Its place of manufacture is unknown, but it was found in the Rhone near Avignon in 1656. It was long known as the Shield of Scipio, because the scene was thought to depict that famous Roman. Among the largest known of its kind, the plate indicates the size and luxury of antique silverwork commissioned by pagans and Christians alike. Bibliography: Chabouillet, 1858, no. 2875; Babelon, 1900, no. 2875; Levi, 1947, I, p. 48; Carandini, 1963-1964, pp. 15-16, pi. in, fig. 7.

The Vergilius Vaticanus: Aeneid. Rome, 1st quarter 5th century. Parchment

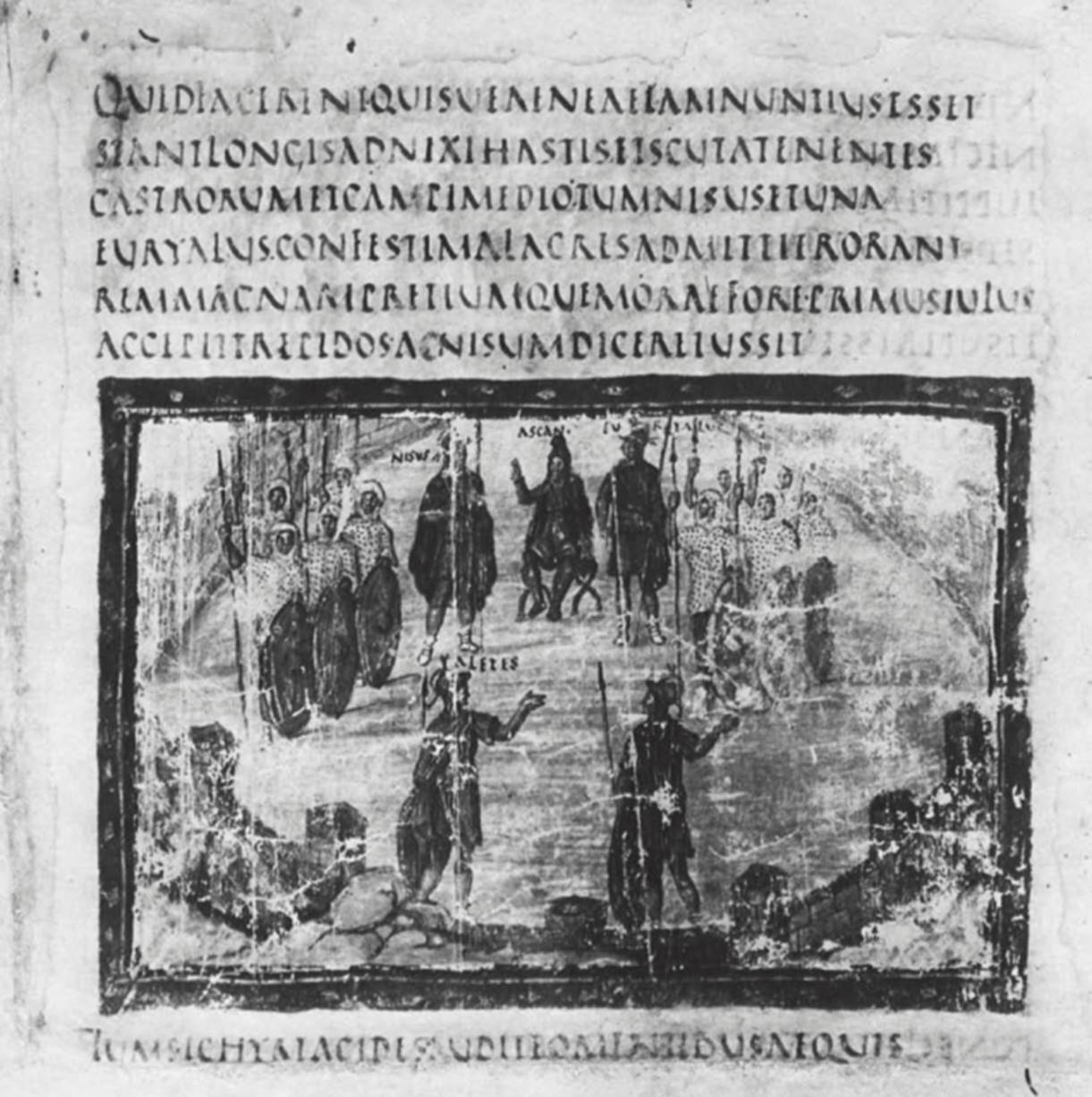

Two illustrated manuscripts of Vergil from the Late Antique period have survived (see also no. 204). The Vergilius Vaticanus, the older of the two, includes both the Georgies (no. 224) and the Aeneid; less than a fifth of the original manuscript is preserved. The illustrations consist of framed pictures, usually inserted into the text but sometimes taking up a full page. Although there is reason to suppose that a nucleus of the illustrations depends on an earlier cycle (Weitzmann [1], 1970, p. 106), we do not know when the first Vergilian picture cycles were created. When the poet's text deals with themes from Greek literature, Greek pictorial sources were used, but there are also many Late Antique elements that entered the picture cycle as it was recopied and elaborated.

The Vergilius Vaticanus was illustrated by two or more painters; parallels with mosaics (e.g., no. 213) point to a date in the early fifth century. The manuscript probably comes from the same scriptorium, perhaps in Rome, that produced the Quedlinburg Itala (no. 424). The variety of pictorial concepts is illustrated by the following three miniatures.

In miniature 14, the sack of Troy (2. 254-267), the Greeks have left behind the wooden horse, pretending to sail for home. Some of their comrades have emerged from the horse and have begun to massacre the Trojans, who had been at banquet reclining against crescent-shaped bolsters. The combination of bird's-eye and lateral views is a convention typical of this manuscript, derived from Roman paintings and reliefs. The scene probably has the same Greek source as the sack of Troy on a relief of the first century (Weitzmann, 1959, p. 60); a related scene occurs on the shield from Dura Europos (no. 201). The prototype for these pictures illustrated a lost Greek epic poem— either the Little Iliad or the Ilioupersis.

Miniature 26 is a full-page picture of the death of Dido (4. 642-662). The queen has mounted her funeral pyre by the ladder at the left and now reclines on her marriage bed, holding Aeneas' sword, with which she will kill herself. We look into a room drawn in perspective, with receding walls and coffered ceiling. Spatial incongruities in the scene include the position of the pyre and the placing of the door. The pyre, moreover, should be out of doors, according to Vergil.

Miniature 49 shows Nisus and Euryalus in the Trojan camp (9. 230-313). The two soldiers have volunteered to break through the enemy lines and summon Aeneas. They have addressed the Trojan council, presided over by Aeneas' son Ascanius, and their daring spirit is praised by the old soldier Aletes, seen below. We look into the camp from above, as in miniature 14. The scene is quite symmetrical: Ascanius is flanked by Nisus and Euryalus and balancing groups of soldiers. The figure beside Aletes was added for the sake of symmetry and is not called for by Vergil. Similar compositions occur on historical reliefs from the second century on.

In the Renaissance the Vergilius Vaticanus belonged to distinguished collectors, among them Pietro Bembo and Fulvio Orsini. The latter bequeathed it to the Vatican Library in 1600. Bibliography: Fragmenta, 1945; Bianchi Bandinelli, 1954; de Wit, 1959; Weitzmann, 1959, pp. 59-60; Buchthal, 1964.

The Vergilius Romanus: Aeneid. Color plate VI. Place of origin uncertain, late 5th century. Parchment

The second of the two Vergil manuscripts in the Vatican Library has an almost complete text of the Eclogues, Georgies (no. 225), and Aeneid. The nineteen miniatures were for centuries considered inferior products; but recently their rough, expressive style has been better appreciated. The Aeneid miniatures are all full-page and framed. As in provincial art in general, there is less interest in three-dimensional space than in a neatly laid-out surface. The figures lack classical structure and proportion; faces are mostly expressionless masks, with staring eyes, seen either in three-quarter or profile views. The linear drapery obscures the bodies; gestures are often exaggerated for emphasis. Two pictures exemplify these qualities.

In miniature 13 (fol. 100v) where Dido and Aeneas are shown banqueting (1. 697 ff.), the artist has created a crystalline image. Under an awning, Dido and Aeneas recline on bolsters. Before them is a crescent cushion decked with ribbons and a round table bearing a silver plate with a fish. Below are two attendants. The scene is rigidly symmetrical. The Trojan at the right is unidentified; like a similar added figure in miniature 49 of the Vergilius Vaticanus (no. 203), he is required by the compositional schema and does not appear in the text. The colors are particularly striking, though not at all classical; orange and yellows daringly encompass the lavenders of cloaks and cushions.

In miniature 15 (fol. 106), Dido and Aeneas have taken shelter in a cave, after the goddess Juno contrived a thunderstorm to bring them together (4. 160 ff.). The artist depicts their embrace, more discreetly than the text would have it. Their horses are tethered outside and above are two guards, one of whom protects himself from the rain with his shield. The tapestry effect is especially apparent here; there is little depth or overlapping, while the picture field has an almost uniform density.

Through comparison of miniature 13 with a similar scene in a Constantinian sarcophagus in Modena, Rodenwaldt (1934, p. 295) attributed the manuscript to northern Italy and dated the prototype to the fourth century. Yet the date and provenance of the Vergilius Romanus are still much disputed, largely because of the unclassical style for which there exists no good parallel. An origin in Gaul has also been proposed. Since none of the ten Aeneid pictures illustrates a passage that also appears in the Vergilius Vaticanus, the picture cycles cannot be compared. The Vergilius Romanus may have been taken to northern Europe by Charlemagne (Bischoff, 1965); it was at St. Denis until the fifteenth century, when it came by uncertain means to the Vatican. Bibliography: Picturae, 1902; Weitzmann, 1959, pp. 60-61; Bischoff, 1965, pp. 46, 61-62; Carandini, 1968, p. 348; Rosenthal, 1972, pp. 54-57, 60-63.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 150;