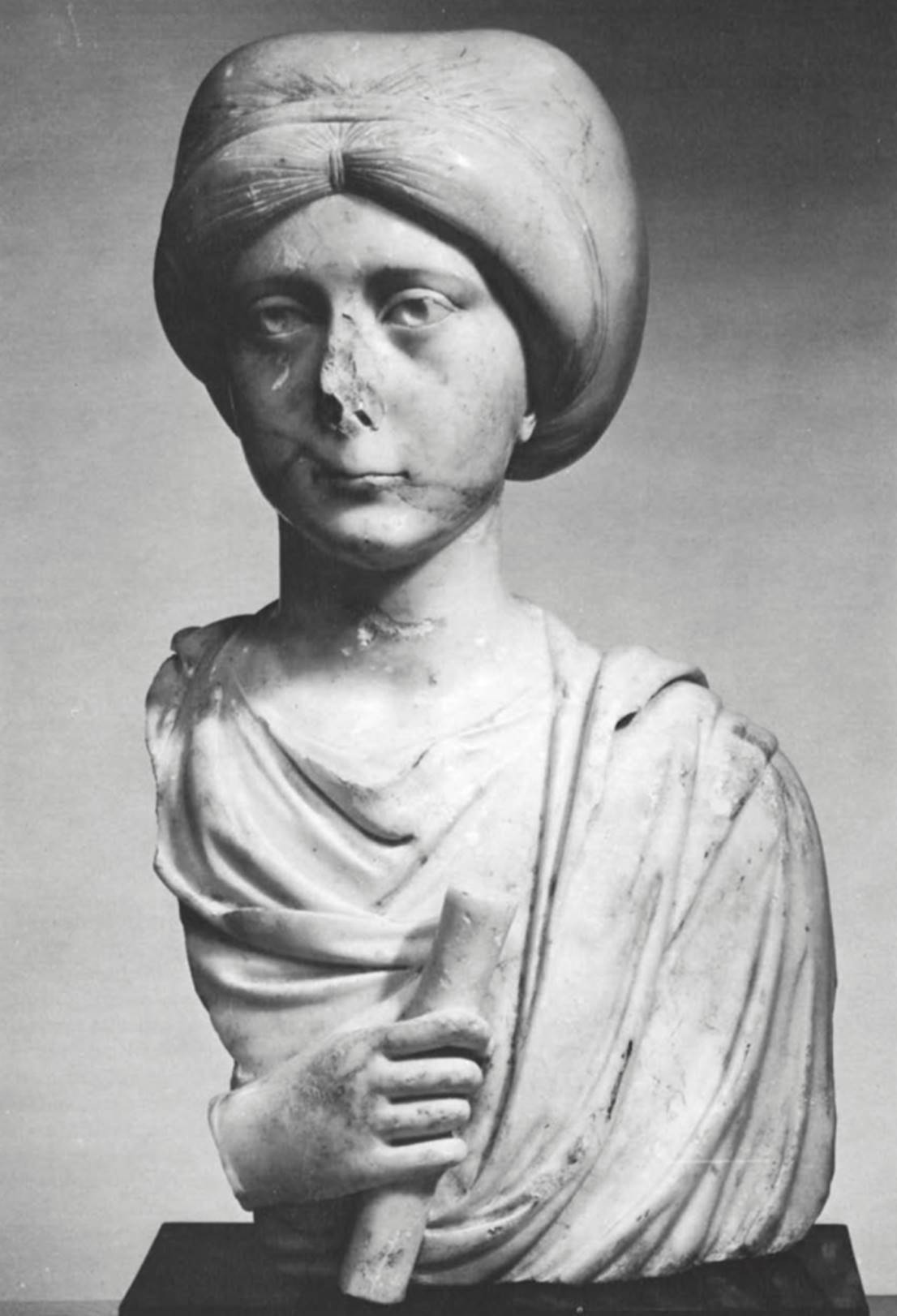

Bust of a lady of rank. Constantinople, 1st quarter 6th century. Marble

The bust of a young woman was carved from one block of marble. It is broken diagonally across lower part of face, through the mouth. Fitting the halves together left only a few small chips missing at the join, with only minor losses otherwise, among them the bridge and tip of the nose. The finely polished surface shows signs of incrustation from burial.

The woman is clad in a long-sleeved tunic covered by a mantle, which conceals her left arm; the right hand holds a scroll in front of her breast, but her right shoulder and arm were sawn off in antiquity. The back is hollowed out, with a slight protuberance in middle toward lower edge; a deep circular hole on underside has remains of a metal pin. Given the slight turn to the right, it has been agreed the bust was probably once part of a husband-and-wife double portrait (usually made for funerary memorial).

The eyes are hollow under sharply cut upper lids and hairless brows; the mouth is tight and thinlipped. The hair is covered by a thin scarf or snood, clipped above center of forehead and covering all of the hair and all but lobes of ears. Variations of this coiffure appear as early as about 400, as on the figure of Serena on the diptych of her husband Stilicho (Volbach, 1976, no. 63); but only in the sixth century did it become the dominant style for ladies of the court, including Theodora herself (Alfoldi-Rosenbaum, 1968, pp. 27-28).

While a challenge to the actual authenticity of the bust (by von Heintze, 1970; von Heintze, 1971), has been effectively refuted (Alfoldi-Rosenbaum, 1972; cf. Sande, 1975), the extremely high quality, as well as the strikingly classical form and expression, make an attribution to the Theodosian renaissance (by Sande, 1975) most attractive. On the whole, however, Alfoldi-Rosenbaum's arguments for a Justinianic date are more persuasive: the vertical lines of the mantle over the left shoulder are indeed “incongruous" even by the standards of most classical revivals, while the completely hollowed eye pupils occur only in the portraits of Ariadne (nos. 24, 25) and later works such as the ivory of the archangel (no. 481). Above all, the near identity in profile, including the frontal surfaces of the face, between this head and that of Theodora in Milan (no. 27) sets these works apart from Theodosian ones like the Paris Flacilla (no. 20).

The fact that most surviving sixth-century portraiture in life size is of far weaker character is probably no more than historical accident, through the loss of so much of the art of Constantinople itself. Only in the so-called minor arts, such as the archangel ivory and the series of classicizing silver plates and bowls (no. 232) can the proper comparisons for this superb work be found.

Forged in Constantinople: Luxury Arts and Imperial Gifts in Late Roman & Byzantine Daily Life

By late Roman and Byzantine times what are sometimes called the sumptuous arts—jewelry and other works in precious materials—had become important art forms. Though seldom preserved, such objects are often mentioned in texts. Representations from Constantinian times through the seventh century— such as the early fourth-century frescoes discovered in Trier (fig. 34), the fifth-century mosaic in Sta. Maria Maggiore in Rome (fig. 35), and a drawing in Naples (no. 29)—show many gold and jeweled vessels and an abundance of jewelry, articles clearly of significance and value for those who could afford them.

Fig. 34. Ceiling fresco showing a woman with a jewelry box. Trier, cathedral

Fig. 35. Mosaic with Moses before Pharaoh's daughter. Rome, Sta. Maria Maggiore

For members of the imperial family, for high officials and their families, and for the very wealthy, the sumptuous arts were part of everyday life. A freedman, however, was permitted only one gold ring. Gold was the basis of trade in the empire— especially for hiring foreign mercenaries and for controlling the barbarian tribes on the borders—and its use had to be limited. The Church, particularly in the great centers, ranked with the court in its use of objects of gold adorned with jewels.

For a long time, scholars tended to ascribe the origin of these luxury arts to the parts of the empire where they were found in modern times. This method could be true for the Late Antique period, when such cities as Rome, Antioch, Alexandria, and others were still wealthy and flourishing. But even for those centuries, both artists and objects could be easily transported. A series of silver bowls found together and now in Munich were used as imperial largess by the emperor Licinius I. Two of them, however, though nearly identical, bore inscriptions indicating that one was made in Nicomedia and one in Antioch. They could have been made by the same silversmith moving from one imperial mint to the other, but had they not been inscribed they would wrongly have been given the same place of origin.

In the fourth and fifth centuries the jewelry found in Rome resembled that found in the Eastern Empire, giving rise to the concept of an “international style" (Segall, 1938, p. 143). Beginning in the Constantinian period, mints for striking gold coins usually functioned near the court, and artists would be called from one mint to another (Bruun, 1961, p. 24). The imperial jewelers were connected with the mint under the control of the comes of the Sacred Largess. Gradually, Constantinople became the empire's chief artistic as well as political center. The regional mints were greatly reduced in number. Emperors and members of the imperial family moved about less and less, and, after the last Western emperor abdicated, they rarely left Constantinople. Artists were always concentrated where the demand for their work was the greatest.

In Egypt, where Alexandria had been a great art center, the luxury arts gradually disappeared. This is particularly notable in the so-called Fayyum portraits, where elaborate jewelry is shown through the third century and then is progressively eliminated in fourth-century portraits (no. 266). Likewise, in the tapestries attributed to Egypt, jewelry is rarely represented after the fourth century.

Silver began to be hallmarked in Constantinople at the end of the fourth century. Study of the five control marks of Constantinople on silver of the sixth to seventh century demonstrates that Constantinople had become the chief center for the manufacture of silver objects that were distributed from there throughout the empire, and even beyond (nos. 141, 232, 425-433, 547). A few scholars still claim that the silver was produced in Antioch and was sent to Constantinople to be stamped, then returned to Antioch to be finished—but such a long and costly voyage would have put any silversmith out of business. Any Syrian influence seen in Constantinopolitan silver can be explained by the migration of Antiochene silversmiths to Constantinople to seek employment after the decline of Antioch; they would have taken with them their techniques and the socalled Syrian Style. Thus, the silversmith's art and naturally that of the goldsmith as well—became concentrated in Constantinople.

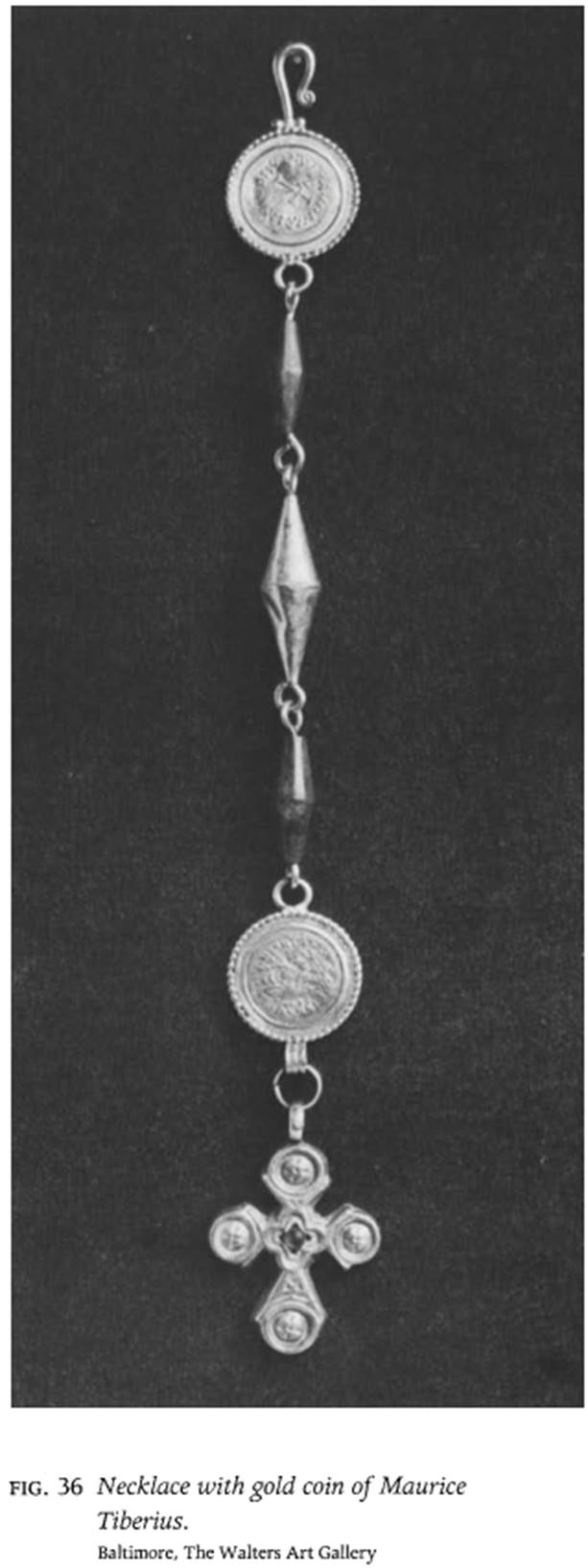

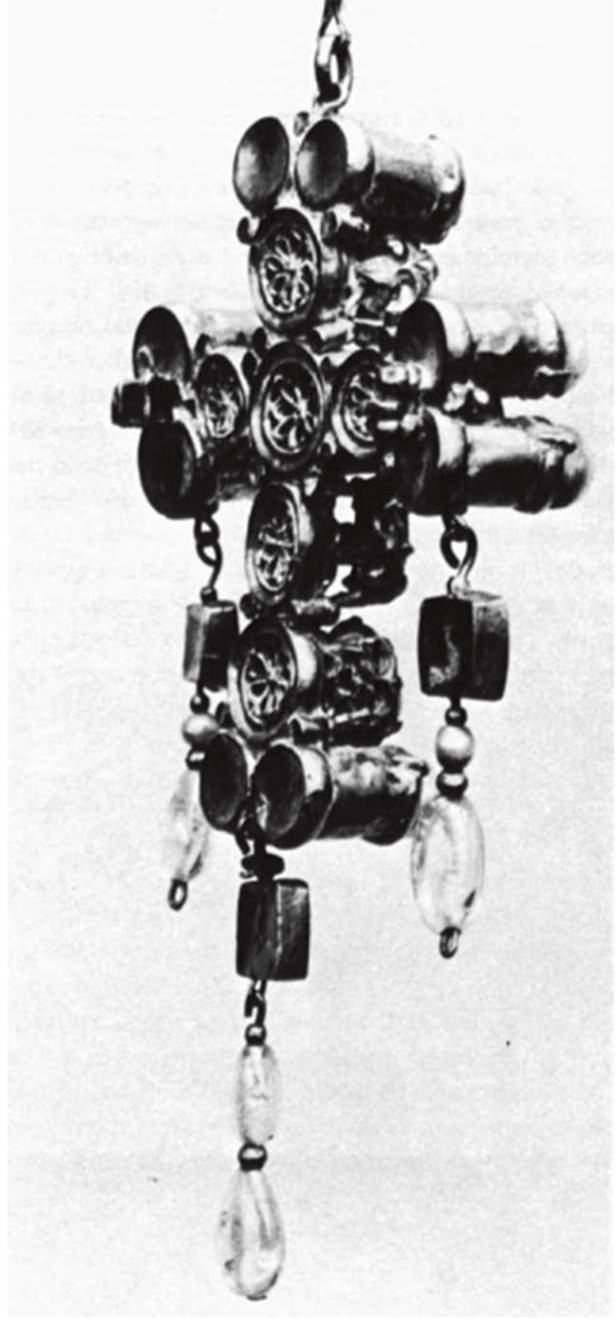

By the sixth and seventh centuries Constantinople was apparently also the place of origin for much of the finest jewelry distributed throughout the Mediterranean world. Common to many pieces of jewelry from widely scattered find-sites is a gold or gold and lapis lazuli bead made like two cones fitted base to base. This motif is also found in necklaces (no. 288) and was sometimes used for bracelets and earrings. It also occurs in the clasp of a necklace found at Cyprus with silver bearing the five Constantinopo- litan control marks and in gold medallions struck in Constantinople (no. 295). Other pieces of this type were found at Messina, Sicily, and the island of Lesbos. An approximate date for this group can be assigned on the basis of a necklace fragment in the Walters Art Gallery that is set with a gold coin of Maurice Tiberius (582-602; fig. 36) and another one in Pforzheim that has a portrait of Tiberius II (574- 582; fig. 37). Bracelets are usually found in pairs, and we know from the mosaics of Ravenna (nos. 65, 66) that they were customarily worn in pairs.

Fig. 37. Detail of necklace with portrait of Tiberius II. Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum

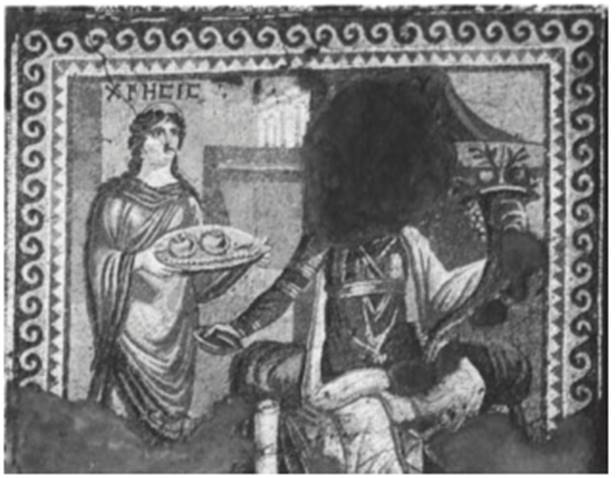

Fig. 38. Chresis mosaic with gift offering of jewelry. Antioch

The explanation for the widely scattered find-sites is that such objects were bestowed as imperial gifts on loyal retainers. Such gifts were instrumental in the administration of government, and thousands of items of arms, armor, and clothing were given to high-ranking soldiers and civil servants each year. Other such gifts included silver, ivory, glass, embroidery, textiles, special issues of coins, bowls in silver or glass, and jewelry. Among the jewelry from the fourth to fifth century that can be attributed to imperial workshops are: a fibula presented to Constantine the Great (no. 275), a pendant from an imperial necklace (no. 276), a diadem (no. 277), a gold ring probably presented to a victorious general (no. 278), and a jewel made for the empress Maria at the time of her marriage to the emperor Honorius (no. 279). Like others in the imperial mint, the jewelers doubtless followed the movements of the court, prepared to supply pieces of jewelry for gifts whenever needed.

By the sixth to seventh century, court life focused on Constantinople, but the tradition of imperial gifts continued. From the Chresis mosaic (fig. 38), found in Antioch, we know that a necklace, a brooch, or a fibula, and a pair of bracelets were considered appropriate gifts. Thus, the pair of bracelets found in Cyprus was probably an imperial gift. Necklaces and bracelets found in Egypt in modern times (nos. 296, 298) were probably either sent there as gifts or taken by great families back to Egypt when they returned from a visit to the court. This could explain why such jewelry of the late sixth and seventh centuries reached Egypt long after Alexandria had lost its place as a great art center. The same would be true for Syria. Naturally, jewelry would continue to have been made in such places but not pieces of great splendor. Jewelry covered with pearls as in nos. 284 and 300 recalls the exuberant use of pearls in the jewelry of the empress on the ivory from Vienna (no. 25).

A jeweled cross decorated with sapphires (fig. 39; cf. bracelets from Cyprus and Varna, nos. 298-300) has rightly been called an imperial gift from Constantinople, although it hangs from a votive crown with the name of Receswinth, king of the Visigoths.

Fig. 39. Cross from the crown of Receswinth, king of the Visigoths. Madrid, Museo Arqueoiogico National

The finding of a gold rosette in Constantinople like those on the back of the cross of Receswinth from Guarrazar confirmed that the cross was made in Constantinople, since the rosette was probably not imported. In addition, the Varna bracelets (no. 299) were found with a gold and jeweled diadem. At this period such a diadem could only have come from Constantinople, an origin confirmed by its style.

Glyptics were another of the sumptuous arts popular with the imperial court and with the great families for their own use as well as for gifts. Formerly, important pieces were known only from the fourth and early fifth centuries, but Noll's (1965) discovery of the magnificent sixth-century Crucifixion in intaglio, now in Vienna (no. 525), which he rightly believes to be an imperial gift, shows that important glyptics were made much later than had previously been thought. Many imperial and other portraits were made in cameo and in intaglio, some even in the round, especially from the fourth century. Other magnificent glyptics are the Rubens vase (no. 313) and the two crystal lions' heads (no. 330). The lions' heads were probably made in Trier, the site of an imperial workshop.

Gold domestic plate and liturgical vessels—such as a gold cup (no. 156) and gold perfume bottle (no. 312)—were manufactured in much larger quantities than one would think today from the few that have survived. Texts mention, for example, the gold plate used by Justin II at his coronation banquet, which was decorated with the triumphs of Justinian I. Moreover, gold liturgical vessels can be seen in the Ravenna mosaic (nos. 65, 66). Silver vessels, both domestic plate (see spoon, no. 316) and liturgical vessels, have survived in much greater numbers. The Projecta casket (no. 310) recalls the jewel boxes seen in the Trier fresco (fig. 34) and in the Sta. Maria Maggiore mosaic (fig. 35). St. Augustine lamented that he had to give up his silver fork, indicating that it was usual to have one.

Bronze was very much a part of Greek and Roman art, and in the Late Antique and early Byzantine periods bronze continued to be used for statues and statuettes, as well as for everyday objects. Full-sized statues are mentioned in texts but are mostly now lost. Many of the statuettes of emperors and empresses that are still extant were used as weights (nos. 13, 327, 328). The latest of these imperial weights is that of Phocas now in the British Museum. Flat weights inlaid with silver exist in abundance, with letters indicating the weight and often with imperial figures (nos. 324-326). The elegant weights would have been issued from the imperial mint on instructions from some high official. Splendid examples like these would have only been used by an important personage; the emperor Julian decreed that an official —called a zygostates—should be appointed in each city to check gold coins.

Many types of lamps together with their stands, and sometimes with small statues, were made for churches and for domestic use (no. 318). Incense burners (nos. 563, 564) were necessary in the liturgy and to keep the churches and houses smelling fresh. Two miniature bronze lampstands bring us closely into contact with the everyday life of the soldier; one has a lamp held by a soldier—probably the image of an officer's attendant—on the end of his sword (nos. 319, 320). One or several of these would have been used to light an officer's tent and could be folded for travel.

Though the most luxurious of these objects were the actual possessions of only the most privileged class of Late Antique society, they were, in a sense, “everyday" objects for all classes. Whenever the emperor and empress and members of their court appeared before the public for official celebrations, they would be dressed in rich robes and adorned with jewels. Governors of provinces appearing to the public would wear their gold, often jeweled “belts of office." Generals would appear before their troops in splendid armor decorated with gilding. In Constantinople, on great days and on the visits of ambassadors or for triumphs of generals, the populace was required to display their plate and rings along the route to be followed by the procession. With church objects—the gold, silver, and sometimes jeweled liturgical vessels, crosses, lamps, and other furnishings—the public also was able to see and enjoy the splendor. Thus, these objects provide us with some conception of life as it was lived in the first centuries of the Christianized empire.

Marvin C. Ross. Bibliography: Zahn, 1932; Segall, 1938; Bonicatti, 1961; Downey, 1961; MacMullen, 1962; L'Orange, 1965; Grabar (1), 1966; Grabar (1), 1967; A. Alfoldi, 1969; Overbeck, 1973.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 152;