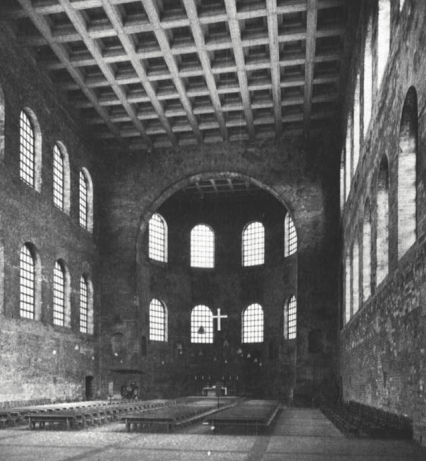

Aula Palatina. Trier, about 305—310

Trier, a provincial capital, became an imperial residence under Maximian (285-305) and was a seat of Constantine I and his successors. Their palace stood on a natural terrace in the eastern part of the city, extending from the cathedral (no. 583) to the imperial baths. Near the middle of the terrace stands the Aula Palatina, one of the most luxurious Roman buildings in northern Europe. It is believed to have been the emperor's audience hall. On the evidence of coins and brick stamps its construction can be placed around 305-310. Although it has lost its decoration and its ceiling, as well as the original south and east walls (rebuilt in the nineteenth century), the Aula retains a rare majesty, and much of its decor can be reconstructed from remains.

The spacious, apsed hall was preceded on the south by an elongated apsed vestibule. Courtyards on the other three sides served as light wells for the enormous windows. Wooden galleries, reached by stair towers flanking the apse, permitted the repair and cleaning of the windows; the lower gallery also gave access to the exhaust ducts of the heating system, which rose inside the pilasters to the level of the lower sills. The pilasters continued upward to arch over the second row of windows—a manner of articulation soon to find favor in northern Italy. The brick masonry, unique in Trier, was hidden by grayish plaster.

The pragmatic, colorless exterior was the antithesis of the interior, where the walls were covered with variegated opus sectile to the height of the upper windowsills and with painted plaster above. Except for a cornice under the lower windows and the seven niches in the apse, the decoration was generally flat, so that the patterned wall and the translucently glazed windows appeared as a vibrant, continuous thin screen. An impression of pomp and grandeur was enhanced by optical tricks. The motifs in the revetment patterns—including pilasters and other architectural members—were small, causing the total wall surfaces to seem higher and farther away. To make the apse seem deeper, its windows were made smaller than those in the side walls, and the top row was set more than 3 feet lower.

As a building type, the Aula Palatina was not unusual: witness the similarly shaped reception rooms at SpUt (no. 104), at Piazza Armerina (no. 105), and in earlier palaces. But it differed from its predecessors in conception and from its contemporaries in degree. The heating system was unusually complicated, allowing all or only part of the building to be heated, as circumstances required. The decor was novel; despite a lack of well-preserved interiors for comparison, many scholars believe that the tapestrylike appearance of the wall was a recent development, at least in public building, when the Aula in Trier was designed. A similar mode may have been adopted at Piazza Armerina, as in other contemporary buildings and later at Ostia (no. 340). Trier exceeds them all, not only in the well-known Tetrarchic values of size and opulence, but also in the equally prized, if less frequently attained, qualities of subtlety and sophistication.

Bibliography: Reusch, 1965; Krautheimer, 1967; Gunter, 1968; Wightman, 1971, pp. 103-109.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 330;