Villa. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, about 306-310

A magnificent villa at Piazza Armerina, inland from Gela, was excavated in 1950—1955. It is one of the finest known examples of baronial architecture under the Tetrarchs, especially interesting because of its extraordinary complement of polychrome mosaic pavements, covering some 36,584 square feet of floor space (no. 91).

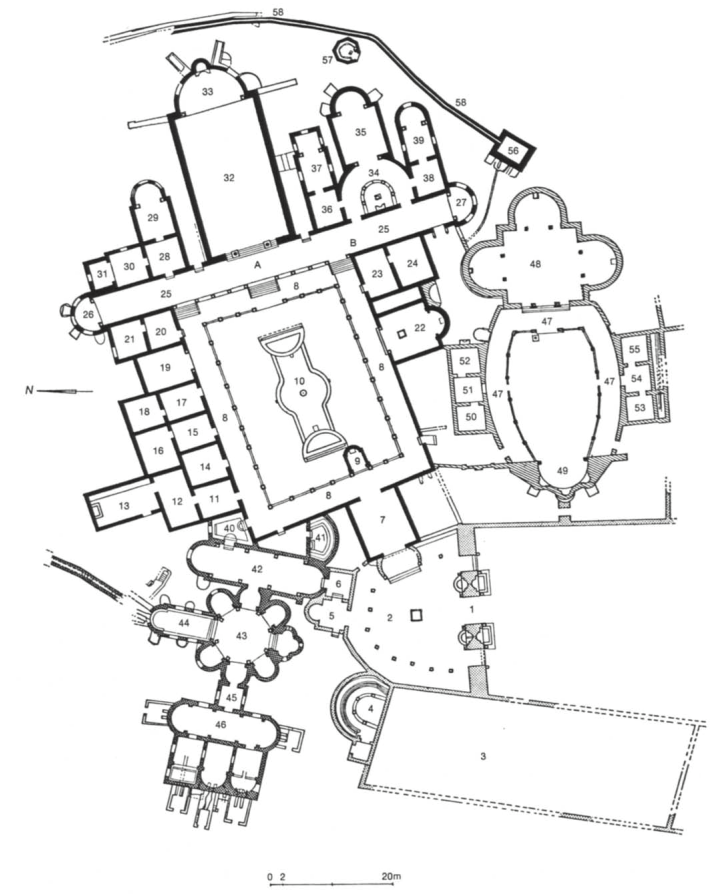

The construction of the villa followed the destruction of an earlier one on the same hillside site. The slope was newly terraced to accommodate a cluster of distinct but interconnected buildings: entrance court (2 on diagram); peristyle and adjoining rooms (8-39); bath (42—46); and triconch (48). A rough axis through the peristyle seems to divide the domestic quarters, to the north, from the more public rooms grouped at the south. The northern rooms include the bath (frigidarium, 43-44; tepidarium, 45; caldarium, 46), a kitchen (13), servants' quarters (20—21), and a bedroom suite (30-31). Chief among the public rooms was the large reception hall (32-33), with a place for a throne in its apse (cf. no. 102). South of it a smaller apsed room, probably for dining, opened on a charming sigma courtyard with a fountain. This suite may have been intended for informal entertaining, while truly ceremonial dinners were probably conducted in the triconch, which also faced a fountain (49) across a unique ovoid court.

Certain architectural motifs, like the triconch and the suite around room 35, seem to reflect the fashions of North Africa, and the brilliant mosaic pavements are generally attributed to itinerant North African ateliers. But the design as a whole, in its seemingly casual aggregation of self- contained units, may be of Italian descent. Although the grouping of components at Piazza Armerina is dense, the sense of variety and isolation found in sprawling earlier villas like that of Hadrian near Tivoli has been cunningly recreated by the dictation of tortuous and disorienting routes. The audience hall, for example, lay directly opposite the vestibule (7) but was blocked from its view by a shrine (9). The visitor entering at (1) had to change his course five times to reach it: turning into (7), twice in (8), to (25), to (32). Care was taken that successive doorways be unaligned (e. g., rooms 17-18, 23-24); long views were systematically obstructed so that the "end" of the villa could never be seen. And at almost every turn a new mosaic pavement or ornamented hall came into view. Typically, decor and design were wholly inner-focused. Despite the monumental entrance (1), there was no real facade; the shape of the exterior was accidental, the result of the conformation of the spaces within (cf. no. 592).

The owner of the villa may be the man depicted in the midst of the enormous (about 191 feet long) "Great Hunt" mosaic in the corridor (25). He wears official dress and insignia, and some scholars believe he is the emperor Maxentius; another portrait in the same mosaic is thought by some to represent Maximian, his father. The villa does incorporate several imperial features, like the audience hall and the image of an adventus in the vestibule mosaic, but in late antiquity members of the lesser aristocracy commonly claimed such perquisites for themselves. This was probably the case at Piazza Armerina. Bibliography: Gentili, 1959; Ampolo et al., 1971; Di Vita, 1972-1973; Kahler, 1973; Polzer, 1973.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 254;